A rabbit runs a swimwear shop. A church has a Patriarch and a treasure chest of Greek Orthodox relics but no congregation. Everybody wants to open a gallery. The government has declared war on the middle-class. This is Istanbul in summer, 2013. A series of apparently unrelated scenarios gradually become linked by a web of business and political machinations. The riot police are not the winners.

Linked stories/novel: approx 200 pages

Read an excerpt from After the Penguins here.

Out now on Amazon Kindle

Posted November 11, 2013 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

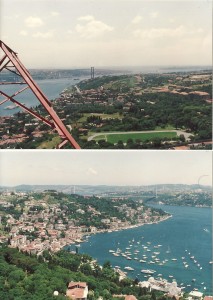

Between Bebek and Kandilli, power lines are strung across the Bosphorus. They hang from two enormous pylons, one on the Asian and one on the European side of Istanbul. Someone on the internet is willing to sell you a poster of the European one. Go for it. The pylons also have their own wikipedia page.

I was of the mindset that if such tall towers existed, they would be worth climbing because the view would be tremendous.

The European pylon was a brief walk from where I was living at the time. There was a broken chain-link fence around the base. I slung my Pentax K1000 around my neck and started upwards. Every ten metres or so, the ladder would change direction. It didn’t take long to be above the level of anything else in the vicinity. At this stage, there was a metal lattice platform so I could have a bit of a rest. I could see both of the suspension bridges over the Bosphorus and a panorama of Bebek and the Asian shore that I hadn’t seen before. There was a strange whooshing sound just next to my face. I saw a blur moving fast away from me. It grew smaller and flattened out into a bird shape. I must have disturbed it.

I kept going up. If I looked down, I could see how far up I was. I don’t get disturbed by heights but I still didn’t want to look down. I caught a movement from the corner of my eye. The bird was returning. It was very fast. Before I knew it, it was brushing past my head. I caught a glimpse of mad, staring eyes as it passed me. It would be back.

I kept going. On the next lattice floor, there was a pile of twigs and fluff. The fluff was made up of little white balls that extended beaks at me. No wonder the falcon was diving at me. I crouched as the thing flew at me again. I needed to get away from its nest. I kept going upwards. It made another half-hearted dive but that was it.

The view from the top was amazing. At the very top of the pylon was a part that stuck out to both sides. The ladder all the way up so far had been surrounded by a sort of cage. If I fell, there would be something to grab. The ladder up the very topmost few metres was a simple, unprotected set of rungs into the sky. The view was amazing but if I went up that last few metres, I would be able to see the entrance of the Bosphorus into the Sea of Marmara. It would make a much better picture.

On the way down, the Peregrine buzzed me again. By the time I had reached the bottom, I was shaking, because of both the height and the attacking raptor. I promised myself I would never do such a silly thing again.

In the next week, I found myself in the ruins of Kandilli Kiz Lisesi, a burned out ruin on the Asian side of the Bosphorus. It was impressive (this was 1991 – It is now beautifully restored) and deserted. I explored a little further afield, making for the base of the electricity pylon nearby. To get to the tower, I had to go through some cemeteries. The main one was Jewish but there was a small section of Armenian graves. On one of them, a great horizontal slab was cracked. One section of it was moved aside. I looked into the grave. Inside was a jumble of bones including at least eight skulls. I’m not sure whether this counts as a mass grave or not but it seemed unusual to have an open grave with bones from a lot of people piled up indiscriminately. If anyone knows the story of this grave, I’d love to hear it.

I was so shocked that I scrambled through the fence and up the pylon. Here’s the view.

I wrote a poem about it later:

The Armenian Question

No guards but I know I trespass.

Memorials in letters I cannot read.

Past graphic Jewish stonework.

Stumble over crumbled walls

From the star to the cross.

An alphabet melts into algebra.

The unliving memory

Unknown, unseen, illegible

To all who could possibly see.

Attracted to the focal point;

The highest cross blocks winter sun.

Wide marble slab; one corner

Shattered from neglect or malice,

Shoved wrenchingly aside.

I edge towards the questing pit.

My sight passes the lip and teeters

On the brink and falls into the dark.

My pupils wide to catch whatever light

Escapes from black hole gravity.

Recognition of the shapes within.

And what else could I possibly expect?

The rounded, staring symbols of events

Of Holocaust, Rwanda and the Khmer

Grinning, as they do, from lack of choice.

And further, past the figureheads of fall,

Meccano struts like tumbled ravens’ nests.

The frames of peaceful dead or tortured end

Exposed by desecration or the years

That lie until a trepid witness comes

Who sees the signs but cannot read the words.

5th Feb 2006

Posted November 11, 2013 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This picture is from an earlier swim across the Bosphorus.

This picture is from an earlier swim across the Bosphorus.

“Do you want to swim the Çanakkale Boğazı?” Mehmet asked me. Mehmet had already swum the Dardanelles a few times and had got me involved in a race across the Bosphorus the previous year in which I had placed close to last in a large field.

But did I want to swim the Dardanelles? I thought of Hero and Leander, Xerxes and the Persian army, Lord Byron, World War I. Of course I did. Or rather, I wanted to have done it. I wasn’t sure about the actual swimming. I remembered Çanakkale Boğazı as significantly wider than its İstanbul counterpart.

“Yes?” He knew I would. “The race is on Saturday August 30th. You have to register in Çanakkale before 5 p.m. on the Friday before.” OK, so now I was going to do it.

. . . . .

My bedraggled-looking 1982 Ford Escort sat there and glared at me. I couldn’t see any loose connections in the electrical system. But when I turned the ignition key, there was no starter motor sound. It had done this three months ago but not since then. I knew if I waited an hour, it would go back to normal and start without any problems. But I didn’t have an hour. I was near Tekirdağ and in a hurry to get to Çanakkale before five.

The Oto Elektrikçi made an eloquent face as I realised how the Escort’s filthy engine compartment must look to a professional. He started it with a screwdriver and some bits of wire, then said it was a dynamo problem and he could fix it in an hour. I didn’t think it was the dynamo, was fairly sure that one hour would stretch to three and I didn’t have an hour to spare anyway. I paid him and continued.

A road map supplied by a major daily newspaper showed a main road along the Marmara coast from Kumbağ to Şarköy. Great, a short-cut. Unfortunately after Kumbağ, the road degenerated into a pitted track covered in grass. Rocks stuck up 30cm from the surface in an engine-threatening manner. Occasional showers of stones bounced across the road from the high cliffs on the right. The recent rains had raised the water table and fresh water bubbled up in the middle of the road. Rockfalls on the right coincided with washaways on the left.

The car hated it. The temperature gauge shot up to maximum and I smelled steam. I didn’t dare stop. I had only seen one vehicle since Kumbağ – some brave soul on a motorcycle. The track followed the terrain and the gradients were frighteningly steep. The car swore at me and growled on.

But the views were magnificent. Wild mountains plunged down to the serene Marmara. Secluded beaches nestled in green coves. Cultivated patches were visible on tiny squares of flat land.

I came to a beautiful cliff-hugging village inevitably called Yeniköy and drove past donkeys, goats and curious men outside the coffee-house. The road got worse. Sometimes it seemed to disappear altogether but when I steered through the least rocky areas, there it was again. I was treated to the sight of waterfalls plunging to the road and carving bits of it out.

Then came heaven in the shape of Uçmakdere, a tobacco-growing village with a track leading to a beach. Some lucky Türks had heard about the place and were having their holiday there. One day, I will too.

The road got better after Uçmakdere and the little Escort sped through Şarköy, Gelibolu and into Eceabat to join the queue for the Çanakkale ferry. It was 3:55. I had to catch the 4 p.m. ferry or I wouldn’t be able to register and the trip would have been in vain. I tried to restart the car. Nothing. Same problem.

I would have to leave the car here. But not in the ferry queue. I spotted an empty parking space 100 metres away and started pushing. A friendly simitçi saw my efforts and leaped to help me. Made it. I grabbed my bag, locked the car and ran.

I bought my jeton from a man who looked and moved like a Galapagos tortoise and sprinted through the gate with the simitçi cheering me on. The ferry was moving. I hurled my bag over the raised vehicle ramp, leapt for the railing at the side, clung on and hauled myself on board. I wondered if any other swimmers were training for the race like this.

It seemed a long ferry crossing. I looked around at the coastlines and tried to figure out the race route. They’ll choose the easiest way, I thought. Maybe from that point on the Asian side to that big castle at Kilitbahir, directly opposite Çanakkale. I began to feel quite good about it. The current would carry me most of the way if I got lazy.

I tried not to look down where there was a plague of those enormous purple-tentacled jellyfish which get swept down from the Black Sea. I wondered what it was like to swim through them.

In Çanakkale, I found an office marked “Information” so I went in and asked where I should enter for the swimming marathon. A helpful girl pointed at the road to İzmir on a map. What? I repeated my request. This time, she pointed out some nice swimming bays near Çanakkale. No, no, no. “Yüzme maratonu. Yarın. Çanakkale Boğazı Geçme Yarışması.” “No,” she said with finality.

Someone was listening though, and after a few phone calls, he had found out where I should register. I jumped into a taxi, got to the 18 Mart Stadium and found the right building. A man was waiting for me and helped me fill in my form. Done it. It was 4:57. I congratulated myself on my careful planning and impeccable timing.

I found a pansiyon, then headed back on the ferry to see about my car. The crossing seemed longer than ever and the jellyfish were increasing. Good thing we won’t be swimming this way.

. . . . .

My tyre’s flat. But every car here has a flat tyre. I’ve parked in the place reserved for dolmuş drivers. I guess they didn’t like that. Oh well, better than a wheel clamp and a fine. I change the tyre. The car starts first time and sits there giggling at me.

I drive to the Oto Sanayı, pump up my tyre and put it back on. The Oto Elektrikçi looks at my car. “There is no problem.” I explain that the problem only happens if I have driven fast for a few hundred kilometres. “Bring it back when you’ve driven fast for a few hundred kilometres,” he retorts, and goes away. Meanwhile, a small boy has washed the battery with gallons of water which have seeped through the air vents and made a small lake inside the car. I tip him for this and slosh back to the ferry terminal.

Next day, I find the place where the Çanakkale Rotary Club has set up race headquarters. I meet Peter and Susan, a distinguished-looking American couple. They know the headmaster who hired me at an American school in İstanbul and Susan has just written a book about Troy. We have our blood pressures taken. There is concern when Peter’s is reported as 28 but two leaps of understanding later, it turns out to be 120 over 80. He’s all right.

There’s mass movement afoot so I follow the crowd to two boats and sit on the roof of one with a bunch of alarmingly fit-looking young men who are discussing race tactics. Last on board is Mehmet with his all-swimming family. He says, “We managed to register you by fax. You didn’t need to come yesterday but we couldn’t contact you.”

The boat starts off. We’re heading towards Eceabat. I wasn’t expecting that. I ask where we start from. “The ferry dock at Eceabat.” It turns out that we’re swimming further than the ferry goes. I start to worry. More than five kilometres? Oh, dear.

Knowing my interest in biology, Mehmet begins to tell me about the sharks that a relative of his saw whilst diving at World War I shipwrecks just beneath us. Some helpful points about how to tell if a shark is about to attack improve my confidence.

The frighteningly healthy youths strip down to purposeful-looking racing trunks and cover themselves in pink grease. They do professional stretching exercises. They agree on the ideal strategy for the race. They will head directly for the very tall radio mast on the European shore. This ensures that they will not be carried too far downstream by the current. Then they will head in a graded curve along the bay and be swept with precision between the buoys which mark the finish. An excellent plan, I think. If only I could have done it.

We reach the ferry dock. Race marshals make sure of numbers and issue bathing caps. I stretch the yellow rubber over my head and presume that now I am safe from any hazards.

Without apparent warning, people start jumping into the sea. I push through a crowd of men with stopwatches and jump into a space between crowds of small boats. The start is a mass of kicking legs as we sort ourselves out into positions in which we can actually start to swim.

I find the radio mast on the opposite shore and commence the enormous task of heading towards it. The Asian shore may as well be the Australian coast for all the hope I have of reaching it. I look back at the ferry dock. To my surprise, it’s already a long way behind. It doesn’t make the far shore look any closer but it’s encouraging.

I put my head down and try to get some distance covered. I look up. Where’s the tower? Turn 30 degrees. Swim again. Eventually, I resign myself to alternating my faster crawl (freestyle) with a breaststroke which gives me a bit of a breather and lets me correct my course.

I bump into a group of swimmers. We recognise each other from the boat, have a short conversation and get back to business. The atmosphere is great. It’s the swimming that’s the problem.

There are dozens of boats around. Knowledgeable-looking men occasionally drive up to me and give me instructions along with a face full of exhaust gases. I look around. Most swimmers seem to be ahead of me and upstream. No matter. I keep swimming towards the radio tower.

The castle at Kilitbahir is now in sight. I’ve swum far enough to see some progress. Head down again. Looking underwater is like swimming in a 60’s Lava Lamp. Out-of-focus blobs of jellyfish everywhere. They’re not too bad so far. None of those Black Sea monsters.

I remember Xerxes and his bridge of boats. How many hundreds of boats did he use? Maybe I could build a bridge of jellyfish. A man on a boat tells me to be careful of the current. I look up. The tower has slipped off to the left a bit.

Leander swam there and back every night? He must really have loved that girl. How did he have any energy left when he got there? Was there any point in making the swim? He must have had muscles like cannonballs.

The jellyfish have disappeared for a while but have been replaced by mats of grass or seaweed which get caught on my hands. I look to the right again. I can see open water to the south-west between the Asian and European shores. I guess that’s why the current is getting stronger. Back to work.

A bit more hard swimming. I can see the buildings of Çanakkale clearly now. A couple of patrol boats up ahead. I see the model of the Nusret, the heroic minelayer from World War I. Just to the left of it is a patch of trees which marks the finish. It doesn’t look too far now.

I remember someone telling me about a negative current if I get too close to the shore. So I don’t. I start swimming straight to the target. There are two or three swimmers near me doing the same thing. Nearly there. One last effort.

I hear yelling. I look up. There is a boat either side of me. People are shouting at me to swim upstream. I look to the shore. I’m level with the Nusret. People standing near it are gesturing urgently towards the left.

And I’ve lost sight of the finish line. I’ve been swept around a point. No negative current here – the entire force of water from the Sea of Marmara is shoving me towards the Aegean. I swim as fast as I can but make no headway. Damn the Dardanelles! The only thing I can do is swim towards the shore.

In the shelter of the land, I can make some progress. But when I get to the little headland, the current hits me again. There’s a boat moored to a jetty there. This is the hardest part. I swim as hard as I can for what seems like ages. I look up. I have moved no distance at all. This is horrible. This is the last time I try to emulate Lord Byron.

I let myself drop back, then swim between the boat and the jetty. That’s easier. I wave at the people peering down through the narrow gap. They give me a bit of a cheer.

I’m through. I swim in calm water to the beach. Mehmet and another swimmer are just taking in the buoys which mark the finish line. That makes me the last official finisher. I stagger onto the shore. I don’t feel really tired, just as if I’ve been on a boat for a week and can’t remember how to walk on land.

“Hello.” Mehmet is unruffled, as always. “I guess you went a bit far with the current.” I watch another couple of swimmers lurch out of the water. I know how they feel.

I meet Peter and Susan. Susan made it despite some early cramps. She’s talking about a swim from Abydos to Sestos, Leander’s actual route in the legend. Peter is looking superior. He got on a boat half way through and doesn’t look dead, like we do.

We watch the awards ceremony. Mehmet, his mother and his younger brother appear an inordinate amount of times to collect prizes. I get my participation certificate, made out in a name that almost, but not entirely, unrecognisable as mine.

Mehmet’s final words are, “It will be much easier next year. You know where you went wrong.”

Posted April 21, 2009 Posted by admin in Enormousfish

…and the Bosphorus.