A rabbit runs a swimwear shop. A church has a Patriarch and a treasure chest of Greek Orthodox relics but no congregation. Everybody wants to open a gallery. The government has declared war on the middle-class. This is Istanbul in summer, 2013. A series of apparently unrelated scenarios gradually become linked by a web of business and political machinations. The riot police are not the winners.

Linked stories/novel: approx 200 pages

Read an excerpt from After the Penguins here.

Out now on Amazon Kindle

Posted November 11, 2013 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

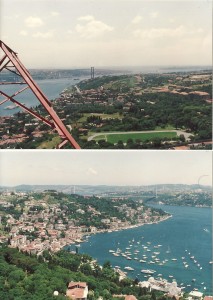

Between Bebek and Kandilli, power lines are strung across the Bosphorus. They hang from two enormous pylons, one on the Asian and one on the European side of Istanbul. Someone on the internet is willing to sell you a poster of the European one. Go for it. The pylons also have their own wikipedia page.

I was of the mindset that if such tall towers existed, they would be worth climbing because the view would be tremendous.

The European pylon was a brief walk from where I was living at the time. There was a broken chain-link fence around the base. I slung my Pentax K1000 around my neck and started upwards. Every ten metres or so, the ladder would change direction. It didn’t take long to be above the level of anything else in the vicinity. At this stage, there was a metal lattice platform so I could have a bit of a rest. I could see both of the suspension bridges over the Bosphorus and a panorama of Bebek and the Asian shore that I hadn’t seen before. There was a strange whooshing sound just next to my face. I saw a blur moving fast away from me. It grew smaller and flattened out into a bird shape. I must have disturbed it.

I kept going up. If I looked down, I could see how far up I was. I don’t get disturbed by heights but I still didn’t want to look down. I caught a movement from the corner of my eye. The bird was returning. It was very fast. Before I knew it, it was brushing past my head. I caught a glimpse of mad, staring eyes as it passed me. It would be back.

I kept going. On the next lattice floor, there was a pile of twigs and fluff. The fluff was made up of little white balls that extended beaks at me. No wonder the falcon was diving at me. I crouched as the thing flew at me again. I needed to get away from its nest. I kept going upwards. It made another half-hearted dive but that was it.

The view from the top was amazing. At the very top of the pylon was a part that stuck out to both sides. The ladder all the way up so far had been surrounded by a sort of cage. If I fell, there would be something to grab. The ladder up the very topmost few metres was a simple, unprotected set of rungs into the sky. The view was amazing but if I went up that last few metres, I would be able to see the entrance of the Bosphorus into the Sea of Marmara. It would make a much better picture.

On the way down, the Peregrine buzzed me again. By the time I had reached the bottom, I was shaking, because of both the height and the attacking raptor. I promised myself I would never do such a silly thing again.

In the next week, I found myself in the ruins of Kandilli Kiz Lisesi, a burned out ruin on the Asian side of the Bosphorus. It was impressive (this was 1991 – It is now beautifully restored) and deserted. I explored a little further afield, making for the base of the electricity pylon nearby. To get to the tower, I had to go through some cemeteries. The main one was Jewish but there was a small section of Armenian graves. On one of them, a great horizontal slab was cracked. One section of it was moved aside. I looked into the grave. Inside was a jumble of bones including at least eight skulls. I’m not sure whether this counts as a mass grave or not but it seemed unusual to have an open grave with bones from a lot of people piled up indiscriminately. If anyone knows the story of this grave, I’d love to hear it.

I was so shocked that I scrambled through the fence and up the pylon. Here’s the view.

I wrote a poem about it later:

The Armenian Question

No guards but I know I trespass.

Memorials in letters I cannot read.

Past graphic Jewish stonework.

Stumble over crumbled walls

From the star to the cross.

An alphabet melts into algebra.

The unliving memory

Unknown, unseen, illegible

To all who could possibly see.

Attracted to the focal point;

The highest cross blocks winter sun.

Wide marble slab; one corner

Shattered from neglect or malice,

Shoved wrenchingly aside.

I edge towards the questing pit.

My sight passes the lip and teeters

On the brink and falls into the dark.

My pupils wide to catch whatever light

Escapes from black hole gravity.

Recognition of the shapes within.

And what else could I possibly expect?

The rounded, staring symbols of events

Of Holocaust, Rwanda and the Khmer

Grinning, as they do, from lack of choice.

And further, past the figureheads of fall,

Meccano struts like tumbled ravens’ nests.

The frames of peaceful dead or tortured end

Exposed by desecration or the years

That lie until a trepid witness comes

Who sees the signs but cannot read the words.

5th Feb 2006

Posted November 11, 2013 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

As in that song by The Cure.

I had taken a class on a Biology field trip to a rocky headland at Kilyos, north of Istanbul. The students were all doing transects or whelk counts and I was meandering around in the sun. One of the more mischievous students appeared and said nonchalantly,” There’s a dead man on the beach, sir.”

“Oh really?” I said. “How do you know he’s dead?”

“No ears, sir.”

I went over to have a look. Thirty pupils, three teachers and our driver were arranged in a horseshoe at the top of a cliff. They were all looking downwards. I got there and saw what there were looking at. A man was lying face down on the beach. His clothes were ragged but intact.

“Go and have a look,” said someone. I became aware that everyone was now looking at me. I was in charge. I sighed. I stumbled down the loose cliff face until I was on the sand. The man seemed a lot bigger here. He still wasn’t moving. Definitely dead. I looked up. A row of faces peering down. I was under pressure.

I walked slowly to the man. No ears or nose. Surely that was enough. They were still staring at me. I needed to do something obvious. I bent and touched the ragged shirt on the man’s shoulder. Cold. I had that horrible feeling that he was about to roll over and do something ferocious and needy. He stayed still. There was seaweed around his toes.

I took a breath and knelt. I picked up the wrist. It was heavy and wet like a soaked sandbag. I couldn’t find a pulse. I didn’t really try. It was just for show. I dropped the hand and rinsed my own in the sea. I looked upwards and shook my head. The heads on the cliff above turned to each other. They were satisfied now.

I climbed back up the cliff. “Right, go and get on with your work.” My actions seemed to have given me enough authority for the students to obey.

The driver wandered off to the jandarma post in the town. A smiling man in a blue uniform returned with him. “Happens all the time,” he said. “Russian sailor falls off one of those container ships and nobody notices until the next day.”

I wrote this poem about it later. I don’t know how much sense it makes.

sir, there’s a dead man on the beach

i approach the inescapable

ragged, blue-white starfish

weed swathes one bare foot

face turned to the sand

i have lost my chance of choice

the gallery of watchers

dispensed to me this task

of raising the dead

his clothes are frayed and flayed

hair a wet tousled paintbrush

his ear is gone, a scar

stranding waves lap his shore

i lean, reach out, beseech

him not to come to life

slap me with a heavy need

confront with salt-cold want

17 Jan 2006

Next Entries »