Robert Ousterhout (2008) refers to a wall ‘recently unearthed’ in Unkapanı that has features similar to the Church of Panagia Krina in Chios.

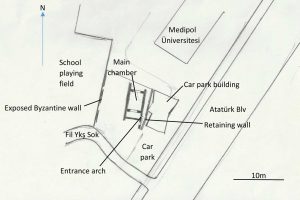

I assume that this is the structure behind the car park of Medipol University Hospital in Atatürk Caddesi (41.02093,28.95906). A retaining wall runs behind the main hospital. The southern end of this wall is broken down and reveals some distinctive arches which point to this being a Byzantine building from the late 12th century. The brickwork is similar to what was left of the Toklu Dede Mescidi, which finally disappeared in the late 20th century. The retaining wall itself appears to be Byzantine, which adds another odd piece to the puzzle.

The building remains to be excavated. I assume that someone has done a preliminary study but I have yet to find anything on this building in the literature. There is one small entrance in the larger of the exposed archways. It is at ground level in the exterior wall but 3 metres above the interior floor.

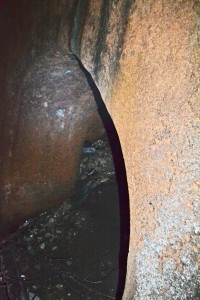

For such a grand window adornment, the entry chamber is tiny, around 5m x 3.5m. It has a brick-domed ceiling and the walls are plastered up to the level of the base of the dome. It is currently filled with branches, as if a hurried gardener needed to find somewhere to hide some prunings. The interesting thing about this chamber is that it has been dug out to floor level, or close to it.

This view from the north shows the retaining wall on the left and the exposed Byzantine church wall on the right.

From this room, a broad archway to the north leads to a much larger chamber, about 9m x 5m. This room is piled high with earth containing a most entertaining assortment of pottery fragments and bones. I remember digging through the rubble and finding, in order, all of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae of a cow. This indicates that, however the contents of the chamber got there, they have not been disturbed for a long time.

The pottery is a mixed bag – tiles, amphorae, plates, pots – some painted and glazed, others natural earthenware. This looks like a place that was used as a rubbish dump for an extended period of history.

One notable piece from this midden is a fragment of painted glass, about 50mm x 30mm. Given the proximity of this building to the Monastery of the Pantocrator, the apparently similar age of the structure and the discovery in the Pantocrator of what appears to be among the world’s first stained glass, this shard may be of significance. It is difficult to say of what this fragment was once part but it bears some resemblance to early glass currently in the Museum of Archaeology.

The main chamber also has a brick-domed ceiling and what appears to be a vertical strengthening rib protruding from the western wall. An arch in the northern side is identical to the one through which one enters this chamber. The room to which this northern arch leads is apparently completely full of debris. Some of the exterior of the eastern wall of this chamber has been exposed and can be seen as one scrambles up the outside pathway to the top of the structure.

The arch to the south of the entry window indicates that there was more of this building in that direction. This remains to be excavated. An abandoned concrete building from the 20th century covers much of the south part of the site. Construction of this may have destroyed the southern part of the Byzantine building.

There is undoubtedly more Byzantine stonework to the west of what is currently accessible. The level of hard-packed debris is uniformly high enough to hide any entrances that may once have led to the western parts of the complex. The prime real estate to the west of Ousterhout’s ‘exposed wall’ is fenced off fairly securely and the homeless population is regularly chased out. There is something exciting under there and I presume that it will be investigated systematically at some stage.

As for what it is, that remains to be seen. The stone and brick, so similar to Panagia Krina, Toklu Dede Mescidi and the south church of the Pantocrator, indicates that his may be a church, or at least a 12th century monastery building. The exposed wall is aligned along the same almost north-south axis the western and eastern walls of the churches of the Pantocrator. However, the accessible chambers have none of the internal features of church architecture. They give the superficial appearance of a narthex.

Perhaps the exposed wall is not from the exterior of the building. Unlike the Panagia Krina, the decorative brick arches could have come from the inside. Mathews’ interpretation of Toklu Dede Mescidi shows the arched section as an internal wall. Perhaps the main body of this church was demolished, leaving the inner narthex. The outside of the eastern wall of the narthex would be the decorative western wall of the nave. There may be an exonarthex on the unexcavated western side. To add to the complexity of the site, there is another arch to the south of the entrance that leads to a chamber blocked off from the accessible chambers. Excavation will reveal a lot.

Mathews, T. (2001) The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Available online at: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/ # Accessed 8th Jul 2016

Ousterhout, R. (2008) Master Builders of Byzantium. University of Pennsylvania Press. Available online at: http://www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/14545.html Accessed 8th Jul 2016

Ousterhout, R. (1995) Beyond Hagia Sophia: Originality in Byzantine Architecture. in A. Littlewood. (ed) Originality in Byzantine Literature, Art and Music. Oxbow Monographs. Available online at: http://eclass.uth.gr/eclass/modules/document/file.php/SEAD343/%CE%A4%CF%81%CE%AF%CF%84%CE%B7%2010%20%CE%9C%CE%B1%CF%81%CF%84%CE%AF%CE%BF%CF%85/Ousterhout-OriginalityByzArchitecture.pdf Accessed 8th Jul 2016

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This takes persistence to find. The location is a piece of open land, clearly with a preservation order because any gecekondu building activity has been swiftly demolished. Hence it serves as a rubbish dump for the surrounding houses and businesses (41027507,28.95476).

In the furthest recesses of this wasteland is a jungle of fig trees and Virginia Creeper. Beneath this is a section of intricately patterned, unmistakeably Byzantine, brickwork. It is the curved eastern wall of the apse of a church that, after the conquest, became Sinan Paşa Mescidi.

Paspates reported in the 1870s that there was a good deal of the church remaining. Now it is difficult to see that there was a building there at all. If you must go and see it, do so in winter when the rubbish smells less and there are fewer leaves obscuring the remains.

This vault was open as of August 2015

In July 2019, the site is securely fenced off and in use for eskici storage and rubbish dumping.

The new excavations that reveal the eastern elevation of the vaults appear to have little to do with archaeology. However, the arches are no longer used for storage. I’ll keep an irregular eye on it.

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

As you walk along Ayakapı Sokak, a blank wall comes into view (41.027883,28.95627). As with many in Istanbul, it bears the marks of alterations and the traces of the many buildings that have been attached to it. At the bottom of the wall, a characteristic Byzantine arch looks tiny because of the inexorable rise of the surrounding ground in the long time that it has stood here. This is what remains of the Ayakapı Chapel.

The wall is now part of a building in which a welding shop operates. The inside provides something of a surprise with a lot more Byzantine stonework than the outside hints at. The welder is knowledgeable about the history of his workshop. In 2014, he was visited by archaeologists from Istanbul University. According to them, Ayakapı Chapel was part of a monastery. The south-east wall of the chapel contained 15 window arches stretching all the way to the defensive wall beside the coast road.

In July 2019, the area is being gentrified. There is a street cafe in Ayakapı Caddesi on the south-east side of the chapel.

The patch of land with the external wall is up for sale and I don’t know what implications this has for the future of the chapel.

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Imperial sarcophagi from the Church of the Holy Apostles, now in the atrium of Aya Irini

This giant Byzantine structure served as the Patriarchate after the Conquest, when Aya Sofya was immediately taken over as the primary mosque of the newly Muslim city. It lasted the short time that Fatih Sultan Mehmet needed to realise that the Church of the Holy Apostles was on the most impressive location in his new possession (1453 – 1456). It was already in a sad state of repair. The first incarnation of Fatih Camii was completed between 1463 and 1470 and the Holy Apostles were no more. The many rebuilds and additions, modifications and subtractions of accessory buildings have meant that anything of the Byzantine church disappeared centuries ago. An ongoing restoration of the entire complex will complete the obliteration of anything that does not remind one of the glory after 1453. (41.019311,28.950369)

The Church of the Holy Apostles was already in a lamentable state immediately prior to the Latin invasion of the fourth crusade in 1204. Emperor Alexios III Angelos, not the most reliable or stable of characters, had spent the contents of the treasury and was faced in 1196 with a demand for protection money from Henry VI of the Holy Roman Empire. Alexios had to plunder the tombs of the emperors, including Constantine the Great and Justinian, in order to raise the funds to avoid an earlier invasion. Some of the solid porphyry sarcophagi are now at the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul. They show clear signs of their desecration in 1196. All this meant was that the Latins found a little bit less to steal eight years later.

In place of the Church of the Holy Apostles, it is appropriate to display a picture of the türbe of Fatih Sultan Mehmet. This stands on the site of the church. Although the church disappeared in the 15th century, it leaves an architectural legacy in the form of a number of churches that have followed its basic cruciform structure of a dome over the centre and four more, one over each arm of the cross. These include the Basilica of St John in Selçuk (once part of Ephesus) and Basilica de San Marco in Venice. The latter undoubtedly has bits of the original Church of the Holy Apostles somewhere in its lucky-dip structure.

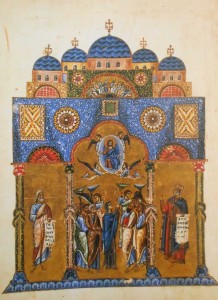

An image from 1162, which matches the description of the Church of the Holy Apostles and hence probably is. Library of the Vatican.

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This fortress of a church is visible for miles around but it tends to be a bit tricky to find in the labyrinth of streets around the new Kadir Has University 41.026912,28.956147). The church looks as if it has been built on stilts. The massive crypt would be a tremendous location for filming a horror movie.

The inner door is locked when not in use so go in at prayer time. Nobody seems to mind if you’re respectful. The restoration of the nearby hamam complex will make this a picturesque neighbourhood.

This is a cross-in-square church from the late 11th/early 12th century with a lot of Ottoman repair and restoration. As usual, the original dedication is lost but reasonable guesses lead to its identification with the Church of St Theodosia. Theodosia was an iconodule heroine who attained her fame at the start of iconclast rule by shaking a ladder that a soldier was using to remove an image of Christ from the Chalke Gate. He died. Theodosia was executed and, with the defeat of iconoclasm became a saint and a retrospective virgin. The present Gül Camii may be the church in which her relics were kept.

There are several other candidates for the dedication of the church but the travelling German scholar-priest Stephan Gerlach decided in the 16th century that this was the Church of St Theodosia. The origin of the current name of Gül Camii (Rose Mosque) stems from the story that at the time of the Ottoman Conquest in 1453, the church was decorated with flowers for the feast of St Theodosia. The Emperor and Patriarch had just conducted the last mass and high-ranking ladies had gathered to pray for a different outcome to the day’s events. When the Sultan’s soldiers entered the church, they were greeted with the sight of roses. It was not until 1490 that the building was renovated and reopened as a mosque but story is that it was named Gül Camii because of those flowers. On the other hand, it seems that an Ottoman holy man named Gül Baba is buried in the building. This may be the slightly less romantic origin of the name.

The two outer apses on the south-eastern face are probably original. They look very much like similar features on the south church of Zeyrek Camii (now plastered over), built at about the same time. The central apse looks very different and probably stems from a restoration in the early 17th century following an earthquake. The dome is probably from this time, replacing a higher one that had been mounted on a drum.

In late January, 2015, there was some laser positioning work going on in preparation for a putative restoration. The painting in the interior comes from the 18th century and shows significant damage from damp. In January 2016, the place looked in need of some attention to stop the plaster from falling on the heads of the worshippers.

Foundation of the Hellenic World. (2008) Theodosia (Gül Camii) Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World. Available online at: http://constantinople.ehw.gr/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=11775#noteendNote_2 Accessed 14th April 2016

Müller-Wiener, W., Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls, Byzantion – Konstantinupolis – Istanbul (Tübingen 1977), pp. 141-143.

van Millingen, A. (1912) Byzantine Churches in Constantinople: Their History and Architecture. Macmillan, London. pp164 - 182

Available online at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm

Accessed 14th April 2016

« Previous Entries Next Entries »