This is nominally a museum (40.996124,28.928665), closed to the public and looking like being so for some years. I fear one of those official restorations (as with Iznik’s Aya Sofya) where an old building is rather insensitively roofed and becomes a sort of propaganda mosque. The first two pictures shown here are from December 1990, when the museum was open and one could see the most magnificent monastery of the Byzantine empire quietly becoming dust.

Founded in 463, this was a place with continuous chanting, where depression was a sin against God and where, if the ruling powers wanted to find some dissident noble or other, he was sure to be skulking in the Stoudion, hoping not to be blinded. It was also the centre of the 9th century Byzantine renaissance. Great works of literature, art and music came from here. Given that this was a hotspot of Christian representational art, the Stoudion’s sun went behind a cloud in the iconoclast era. After the 7th Ecumenical Council in Nicaea put icons back on the Orthodox pedestal in 787, the illuminators of the monastery went into glorious production and achieved world renown. Now only the ruined church and an unroofed cistern remain of this artistic paradise.

It was wrecked in the 1204 crusade, then recovered to survive the Ottoman conquest. Beyazit II turned it into a mosque at the end of the 15th century. An earthquake in 1894 smashed it and it has crumbled until now, when Fatih Belediyesi may do one of their radical facelifts on it. This article suggests that the official plan is to restore the basilica and turn it into a mosque. However, the timeline indicates that this transformation should already have been completed. As of July 2016, nothing appears to have been done since a holding restoration in the 1940s. This involved adding scaffolding to support the remaining bits and tiling the tops of the walls to protect them from weather damage.

It’s still an impressive beast. It’s the only existing Byzantine basilica in Istanbul except for St Mary Chalkoprateia, which is far more of a wreck. It has lovely mosaic pavements and just enough sculpture remaining to hint at marvels from the past. Check van Millingen’s pictures of the place a century ago. The church was still essentially intact although significant damage from the 1894 earthquake is evident. According to van Millingen, the roof collapsed because of ‘an unusual fall of snow’ (van Millingen p49). The fire of 1920 seems to have done a great deal more damage. These pictures from the wonderful collection left by Nicholas Artamonoff, were taken mostly in the 1930s and show a situation recognisable in today’s condition of the Studion.

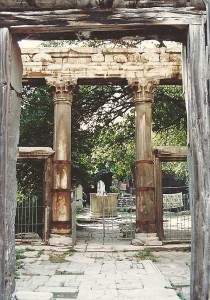

The following pictures are from July 2016. One enters from the west into the atrium. This has a marble fountain in the centre and the remains of cloisters on three sides are still visible. The atrium was used as a cemetery after conversion into a mosque. The surviving headstones add a touch of sculpture to the court.

The iron fence guarding the narthex is the one that appears in Artamonoff’s pictures from the 1930s. The narthex itself is constructed in heavy brick with a large central section and smaller bays to the north and south. The external section of the middle bay is supported by four columns with particularly nice Corinthian capitals. The falling of the western wall since van Millingen’s pictures of 1911 has left the columns on their own, supporting an elaborate and largely complete entablature. The minaret looms over the south bay of the narthex.

The interior of the church was once divided into three sections by two colonnades, the northern one of which still survives with the aid of a lot of scaffolding. The capitals are very worn Corinthian and the intricately carved architraves have been weathered to smoothness. There were once two levels of colonnade, the upper ones supporting galleries.

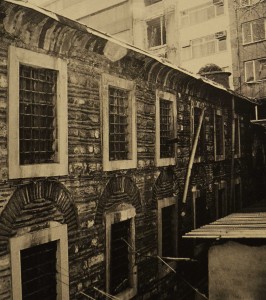

The large apse on the eastern side has little Byzantine about it. The Ottomans rebuilt it with some pleasantly delicate window mouldings but did not extend it so high as in the original building. The bema underwent a great deal of modification in the conversion to a mosque, particularly with regard to adjustments needed to give the mihrab its necessary alignment. There is a small crypt beneath the bema.

The floor of the nave is a highly restorable ex-masterpiece of marble mosaic. It has been open to the weather for a century and the damaging effects of the expanding roots of this summer’s weed growth can be seen. There were once playful figures of rabbits and foxes on the floor but time has erased these. One can see the deterioration in a comparison of the photos from 1990 and 2016. Records exist of the original state of the floor and it would be nice to see it returned to its glory.

To the south of the church is what remains of the cistern. This was once an elegant structure supported by 23 Corinthian columns but is now a sort of wild sunken garden. At the beginning of the 2th century, a small chapel stood to the east of the cistern. Dumbarton Oaks reports that the building was taken over by a distiller in 1944 and that it no longer exists. The site, on Mahzen Sokak, is currently occupied by a recently constructed (and apparently disused) charitable foundation building.

This building is older than the familiar cruciform shape that typifies Constantinople’s Byzantine churches. This is a basilica, built before the new rules imposed by the immense architectural authority of Hagia Sophia. There are no closed-off chapels to the sides. There are doors (now bricked up) opening to the outside at the eastern ends of the aisles. The feel of the church is more similar to the Roman Catholic St Esprit Cathedral in Harbiye than to, say, Kariye or any of the Pantocrator churches. Using a bit of imagination whilst inside the Cathedral of St Demetrius in Thassaloniki might project one into the mindset of a 5th century monk of the Stoudion.

The finest legacy of the Monastery of Stoudios is not in brick and stone; several of the products of the monks’ labours have survived in good condition. The most famous is probably the 11th century Psalter of Theodore, now in the British Library. This has been digitised and some sections of the Psalter can be seen here. The Chludov Psalter is from an earlier period in which the iconophile/iconoclast battle was fresh in the illuminators’ minds. This article analyses what amounts to a 9th century political cartoon in the Psalter.

Two capitals from Imrahor Camii, now in the Church of the Holy Wisdom in Surrey. The official story is that Edwin Freshfield saw some Turks using the capitals for 'revolver practice'. When he protested, he was offered them for one pound. I don't believe a word of it.

Artamonoff, N. (2013-2016) St John Stoudios, Istanbul. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC. Available online at:http://images.doaks.org/artamonoff/collections/show/44 Accessed 10th Jul 2016

British Library: Theodore Psalter (1066) Digitised Manuscripts: Add MS 19352. Available online at: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_19352 Accessed 10th Jul 2016

Levendig, M. (2012) Anonymous: Chludov Psalter (9th Century): Historical Museum, Moscow. The World According to Art. Available online at: http://rijksmuseumamsterdam.blogspot.com.tr/2012/09/anonymous-chludov-psalter-9th-century.html Accessed 10th Jul 2016

Mathews, Prof T. (2001) Hag Ioannes Prodromos en tois Stoudiou The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Available online at: https://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/index.htm?https&&&www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/home.htm Accessed 10th Jul 2016

Müller-Weiner, W. (1977) Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls. Tübingen. pages 147-152

Van Millingen, A. (1912) Byzantine Churches in Constantinople: Their History and Architecture. Macmillan, London. Available online at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm#Page_35 Accessed 10th Jul 2016

Ziflioğlu, V. (2013) Istanbul monastery to become mosque. Hurriyet Daily News. Available online at: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/istanbul-monastery-to-become-mosque.aspx?pageID=238&nID=58526&NewsCatID=341 Accessed 10th Jul 2016

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

The current church is a massive thing from the late 19th century but there was a major monastery here (41.001719,28.932852) from 1031 in which a couple of emperors were buried. The sacred spring (pilgrims still visit the ayazma) seems to have been the reason that the monastery was built here, and the genesis of the Turkish name. The Greek name, Peribleptos, comes from the word for ‘conspicuous’ and refers to the prominent position overlooking Samatya.

Bits of the Byzantine church are here. Mamboury noted that one could see Byzantine foundations from the tram until 1924. These days, one has to hunt among the interesting housing. Fortunately, the inhabitants are interested in what strangers with cameras are doing.

The Byzantine church was a fixture on the pilgrimage trail in late Byzantine times. Gregory of Smolensk, one of the influential Russian travellers of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries saw fit to make two visits to Peribleptos because of the sheer number of relics that it was necessary to kiss (Majeska (1984) p96). Apparently, the hand of John the Baptist was here during his visit in 1389, rather than at the Hebdomon.

The building appears to have become a Latin Church after the 1204 crusade. This meant that when Michael VIII Palaiologos retook Constantinople in 1261, it no longer had a congregation or upkeep. Consequently, it was available for use by the Armenian population after the Ottoman conquest in 1453. It was the site of the first Armenian Patriarchate, which moved to the current Kumkapı location in 1641. There is a nice story that Sultan Ibrahim had a favourite Armenian concubine, named Şeker Parça (piece of sugar) who weighed 150kg or so and had such influence over him that he was persuaded to transfer ownership of the church from the Greeks to the Armenians in 1643. Unfortunately, there is an authoritative source that recognises the church as Armenian from the 15th century. This is now a pleasant and thriving Armenian centre. The schools on the site have a nice atmosphere and it is good to see the Armenian community in such good condition in Istanbul. The ayazma is open at 10am on Tuesdays.

Some of the columns from the Byzantine Church of St Mary Peribleptes were used in the construction of that vast column museum, the Süleymaniye. I have no idea which ones they are – red porphyry, I believe.

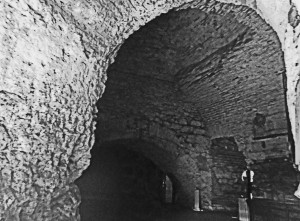

These vaults were mentioned by Mamboury in the 1950s and properly described by Ferudun Özgümüş in 1998

Because the remains of the Byzantine building are limited to the vaults, it is difficult to determine the form of the actual church. Recent studies have compared the configuration of the basement with those of middle-Byzantine churches and come up with a high probability that the Katholikon of the Byzantine Monastery of St Mary Peribleptos was composed of a broad nave with a central octagonal section supporting a large dome on squinches. This is larger than previous reconstructions suggested, and more congruent with descriptions from contemporary pilgrims, especially the excellently named Ruy Gonzales de Clavijo who visited in 1403.

As of July 2019, the vaults are occupied by a welder and family.

The plaster continues to flake off and reveal more of the lovely stonework.

Ball, A, “Peribleptos Monastery”, 2008, Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Constantinople Available online at: http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=12325 Accessed 10th Aug 2016

Dark, K., “The Byzantine church and monastery of St. Mary Peribleptos in Istanbul,” The Burlington Magazine 141.2 (Nov. 1999), pp. 656-7

Majeska, Robert P. (1984): Russian travellers to Constantinople in the 14th and 15th Centuries.Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C.

Mamboury, E (1925) Constantinople: Tourists’ Guide, 1st edition. Rizzo and Son, Constantinople.

Mamboury, E (1951): Istanbul Touristique. Çituri Biraderler Basımevi, Galata.

Mango, C. (2002) “The monastery of St. Mary Peribleptos (Sulu Manastır) at Constantinople revisited,” Revue d’Études Arméniennes 23, pages 474, 489.

Mathews, T and Ö Dalgıç (2016) A New Interpretation of the Church of Peribleptos and its Place in Middle Byzantine Architecture. 4. Uluslararası Bizans Arıştırmaları Semposyumu. Abstract Available at: http://sgsymposium.ku.edu.tr/symposium/abstracts-of-papers2007/thomasfmathewsorgudalgic Accessed 10th Aug 2016

Özgümüş, F. (2000) ‘Peribleptos (Sulu Manastır) in İstanbul’, Byzantinische Zeitschrift 93/2. pages 508-520.

Vin, J.P.A van der (1980) Travellers to Greece and Constantinople: Ancient Monuments and old traditions in Medieval Travellers’ Tales. Nederlands Historisch Archaeologisch-Instituut te Istanbul. Available online at http://www.nino-leiden.nl/doc/PIHANS049.pdf

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Only the crypt remains but it is an amazing piece of brickwork. It is underneath the Church of St Menas (41.00033,28.93202), almost directly across the road from St George of the Cypresses and in an area of Samatya with an unfeasibly high concentration of churches. In the 1990s, it was used as a workshop. The Mobil car service place (Modern Oto) used to be the point of entry. When I went there in 2014, the lovely old couple in the office at the back explained that they used to be able to let people through from there but some decades ago the entrance was blocked up. I decided to hang around the doors on the street frontage, looking suspicious and taking useless photos. Sure enough, after ten minutes, two young men turned up to ask me what I was doing. At first they denied that it had been a church. Eventually, they unlocked the doors and let me in.

The place has had a bit of a transformation. The gorgeous brick dome that looks like the tomb of Atreus is looking better than ever. The space is being used to show films at the moment. The plan is to open it as a café in 2015 but official permission is slow in coming. In the meantime, it is one of the most beautiful buildings in Istanbul.

Van Millingen didn’t know of this crypt as it was only rediscovered in the 1930s. It seems to date from the 5th or 6th century.

As a comparison, here is the interior of the dome in one of the towers in the fortress at Rumeli Feneri

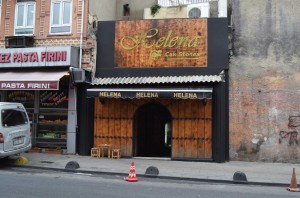

The ambulatorio (closed passage around the outside of the church) did open as a cafe in October 2015. Unfortunately, government regulations mean that the Byzantine sections cannot yet be opened to the public. This has given rise to the ridiculous phenomenon of this cafe inside a beautiful and significant structure being wood-panelled and draped in cloth so the brickwork cannot be seen. Pictures are provided to give the connoisseur some idea of what he or she is inside.

Turkish coffee in hidden splendour

The barista (who makes only çay and really good Turkish coffee) said that the martyrium will be open for business in February 2016, inşallah.

It isn’t. In June 2016, the kahvehane appears to have closed.

Currently a loss-making concern

This reference is the most comprehensive recent guide to the martyrium that I can find:

Beygo, A. (2005) Istanbul Samatya’da Karpos Papylos Martyrion’u. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Istanbul Teknik Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü. Available online at: https://polen.itu.edu.tr/bitstream/11527/7118/1/3687.pdf Accessed 21st June 2016

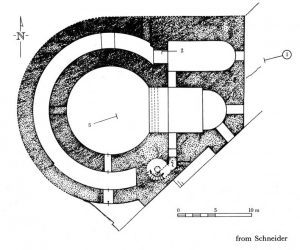

This plan of the martyrium comes from Thomas Matthews’ site: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/

The café is in the ambulatory, the almost circular passage around the outside of the structure. The theatre/cinema section is in the central room. The entrance to that section is into the apse, in the south-east of the building.

This reference is the most comprehensive recent guide to the martyrium that I can find:

Beygo, A. (2005) Istanbul Samatya’da Karpos Papylos Martyrion’u. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Istanbul Teknik Ãœniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü. Available online at: https://polen.itu.edu.tr/bitstream/11527/7118/1/3687.pdf Accessed 21st June 2016

Matthews, Thomas (2001):Â The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Available athttp://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/

Good news… as of July 2019 Helena Stones is back in business.

The proprietors seem to spend their Sundays doing maintenance, particularly electrical work.

The churchyard of St Menas is the roof of the martyrium.

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

There must be some Byzantine bits remaining but they are underground now. As with St Mary of the Mongols, this is a church as it was before the Ottoman conquest. However, the Byzantine structure burned down in a fire in 1782. After reforms in the early 19th century, it was permitted to build churches with domes. Hence the 1832 rebuild was in the form that we see it now. It’s nice to see that at least one of the cypresses planted recently has reached a decent height. (41.000848,28.933364)

The church has been refurbished recently. Here are the results in July 2019.

The yellow-painted plaster has been removed and the newly exposed stonework is in fine condition.

This view of the arches facing the main Samatya road show how much the level of the land around the church has risen in a couple of hundred years.

Some of the attendant buildings retain the distinctive yellow plaster. It is promising to see such a comprehensive restoration in an area bristling with Orthodox churches. This seems to go against the trend of slow disintegration that characterised the last century of neglect of Samatya’s churches.

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

What can you call the Autocephalous Türk Orthodox Church? A nonentity, a grand theft, an anomaly, a political expedient – they all apply. Formed in 1922 in the nationalist euphoria after the eviction of the Greek army, Pavlos Karahisarithis decided that he was the Patriarch Papa Eftim and formed the Autocephalous Patriarchate of Anatolia. He repeatedly invaded the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate in Fener with his supporters. In 1924, he made the politically astute decision to carry out church services in Turkish. He changed his name to Zeki Erenerol and managed to gain a reasonable amount of support from elements of the new republican government. He was given the Church of Meryem Ana in Galata as his headquarters. There were few Greeks remaining in the city after the enforced population exchange and the Erenerols were exempted from exile.

With few Christians left in Turkey and those who stayed deciding to remain affiliated with the Greek Patriarchate, Papa Eftim had difficulty in gaining and maintaining a congregation. In the 1930s, some 70 Garguaz – Christian speakers of a Turkish dialect who lived in Bessarabia – were offered a deal to settle in the Marmara area and become part of the Türk Orthodox Church. Within a few years, they had converted to Islam and left Eftim with no followers. This and subsequent efforts to attract adherents from what could be seen as the wider Turkish community gained the church support from right-wing nationalists. The most prominent member of the Erenerol family, the only people who can remotely be considered as Türk Orthodox, is Sevgi Erenerol. She is serving a life sentence in prison for her enthusiastic participation in the Ergenkon conspiracy, the ultranationalist network of assassins, warlords, politicians and generals that controlled Turkish affairs in the late 20th century. This site from 2008 details one version of the connection between Ergenekon and the Türk Orthodox Church.

Church services ended in 2008 after the widespread allegations that the church had served as a sort of headquarters for Ergenekon. They began again at some stage and by the time this article was published, attendance on Sundays had risen to a congregation of two Erenerols. To give some idea of the incestuous nature of the Turk Orthodox Church, Sevgi Erenerol is the granddaughter of the first Patriarch, the niece of the second, the daughter of the third and the sister of the fourth.

The Patriarchate is the rather lovely Church of Meryem Ana in Karaköy (41.025099,28.978889). This was founded by the Greek Orthodox community of Kaffa (Crimea) and was hence named Santa Maria de Kaffa or Panagia Kaphatiani. Its courtyard bears a prominent banner saying ‘Ne Mutlu Türküm Diyene’. This means ‘happy is the person who says I am a Turk’. This is a nationalist slogan from the early republican era. This is usually written in whitewashed rocks on mountains overlooking Kurdish villages by Turkish conscripts to tell the Kurds that they don’t exist. Here it is written to tell the Greeks that they should be Turks. Fairly obviously, the Ecumenical Patriarchate has never recognised the existence of the Türk Orthodox travesty and still sees the churches as being Greek Orthodox.

The Church of St Nicholas (Aziz Nikola) taken over by Papa Eftim after the 1955 anti-Greek riots. It was damaged in the earthquake of 1999 and is closed for repair. It is partly roofless in May 2014 and looks very sad (41.024482,28.978283). With no congregation and no likelihood of the Erenerol family loosening their hold on this ceremonial ruin, it looks as if it will slowly crumble into the earth.

The Church of Saint John (Aya Yani or Aziz Yahya 41.02507,28.978018) was also taken over by the Türk Orthodox Patriarchate after the riots. Obviously, there was no congregation to fill it so it was rented to the Assyrian Church for a while. I’m not sure whether anyone is using it at the moment. Some sources give the dedication of this church as St John Chrysostomas, others as St John the Baptist (Karaca, Freely). It may have been a politically motivated change in dedication. The Divine Liturgy of John Chysostom is the standard service of the Greek Orthodox community and much importance is given to its exact wording. Clearly, saying the liturgy in Turkish language would mean John Chrysostom’s liturgy no longer being used. Changing the dedication to the better-known and less controversial John the Baptist may have avoided some issues in the Orthodox community.

This final story sums up the Türk Orthodox charade. In 1926, the patriarch took over the Church of Christ. In 1947, the Turkish government announced that the church was to be returned to the Greek Orthodox community. Unfortunately, a road was widened and the church was demolished. Compensation was paid to the Türk Orthodox Patriarchate.

On the first Sunday in October (2014), I was breakfasting in the excellent OPS Cafe just opposite the Patriarchate when I heard the bells of the Panaghia Kaphatiani. For the first time, I found the church open and the atmosphere of a normal church prevailed. There were people lighting candles and praying before the altar and priests preparing the host. When the service got under way, there were seven women in the congregation. Several of them were young and giggly, as if this was their first time in church. The liturgy was conducted by four ecclesiastical personnel. It was odd to hear the ritual spoken in Turkish. Still, it was a genuine church service in a church that all sources had led me to believe was defunct. I’ll go and talk to the caretaker in the near future to find out what is happening in the world of the Türk Orthodox Church.

« Previous Entries