There is a wall inside the construction site for whatever the Belediye is doing to Ivaz Efendi Camii and the towers behind it (41.039432,28.941786). This may be the remains of the Church of St Thecla, converted into a mosque from the Byzantine building. Another candidate for the site of this church is the defunct Toklu Ibrahim Dede Mescidi, the site of which is in a housing estate under construction near Ayvansaray Gate. However, the Church of St Thecla stood within the Palace of Blachernae. Firm evidence for the location of the church will probably never be found, but this Byzantine wall appears to be in the right place. Van Millingen provides an exhaustive summary of the arguments up to 1912.

There is a tenuous argument that Toklu sounds like Thecla so the mescid that once stood in Ayvansaray must have been the remains of the Church of St Thecla. This will only convince you if you want to be convinced of it. A look at Van Millingen’s pictures from around 1912 will show how much of Toklu Dede stood in the early twentieth century. Any remains are now beneath other buildings. This site shows the disappearance of the remaining wall in and around 2012.

I could only take the picture by poking a small camera through a hole in a steel fence and hoping for the best. While I was doing this, a nice turbaned man with three ladies swathed in black (his wife and his sisters) arrived and asked for an explanation of what I was doing. They seemed very interested but their faith in my sanity was damaged when they later saw me photographing an exposed bit of foundation near Eğri Kapı. The exchange went like this:

Man: What’s this?

Me: I don’t know.

Man: Why are you taking photographs of it?

Me: I might find out what it is later.

He walked away smiling and shaking his head. Shortly afterwards, I heard the tinkling of veiled female laughter.

In 2014, the Byzantine structure in the photograph below was visible. It was uncovered during municipal clearing of illegal housing. It is now inaccessible again and guarded by dogs that seem prepared to back up their threats. It lies below the nicely reconstructed Buharlı Emir Tekkesi which is immediately across the road from the ruins usually associated with the Church of St Thecla. Minimal information is here.

Fatih Haber (2014) Tamamı SIT Alanı Fatih Böyle Dönüşüyor. Available online at: http://www.fatihhaber.com/yazdir.php?id=701&t=H Accessed 8th Jul 2016

Mathews, T. (2001) The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Available online at: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/ # Accessed 8th Jul 2016

van Millingen, A. (1912) Byzantine Churches in Constantinople: Their history and architecture. pages 207-211 Available online at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm#Page_207 Accessed 8th Jul 2016

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Underneath the blood red St Mary of the Mongols lies the burnt ruin of a church that served as the orthodox Patriarchate from 1586 until 1596 (41.030331,28.948256). It was the usual basilica type built without dome or towers as dictated by the Ottoman Empire. It was once attached to the palace of the rather interesting Cantacuzene family of Wallachia, which led to it being called Vlach Saray (Wallachian Palace). Or it might be that it is close to the Blachernae Palace and Ayazma – Vlachernae as it is written in Greek. A stone near the entrance has a two-headed eagle, the symbol of the Patriarchate. It was destroyed and rebuilt after fires in 1640 and 1728. After the blaze in 1976, there wasn’t the money to rebuild. Patriarch Bartholomew held a poignant service here in 2011.

Entrance is now through the same gate as the Metochion of Jerusalem.

The picture above shows the north side of the raised platform on which the church is built.

The picture above shows the north side of the raised platform on which the church is built.

In July 2019, the church looks much as it has for the last 10 years with fences around announcing the danger and illegality of trespassing.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

A standard Greek basilica-style church encased in its fortress of walls. The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate was based here (41.037158,28.944924) from 1597 to 1601, whereupon the Patriarch took up residence in the current location.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

An oasis of peace in the good-natured bustle of Balat. The Orthodox Patriarchate moved here (41°01′45″N 28°57′06″E) in 1601 (after eviction from St Mary Pammakaristos and short stays at Vlach Saray and St Demitrios Xyloportas further down the road) and has been here ever since. The church hasn’t because it burned down and was rebuilt in similar form in 1720.

It has a portative mosaic icon of the Virgin Mary, described as ‘very lovely, by Freely and ‘of inferior work’ by Liddell. This icon probably came from the Church of the Pammakaristos when the Patriarchate moved.

There are many, many relics of great importance and greater authenticity than it is possible for any collection of relics to have.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

It’s probably not the Church of St Peter and St Mark but nobody agrees on an alternative. It’s a rather nice mosque right at the end of the Golden Horn walls near the Blachernae Palace (or what’s left of it). 41°02′18.96″N 28°56′38.40″E Apparently, a church was founded here in 458 but this is not it. The main structure seems to date from the late ninth century. Unusually, there is a tomb inside the mosque; that of Cabir, killed with the great Eyüp in the Arab siege of Constantinople in 668.

The building must have had a hefty reconstruction as the mihrab fits perfectly in the focus of the church. Still, it’s a nice place and the gardens are pleasant.

This is a view of the church from the south-west in 2016. Note the polygonal exteriors of the apses as well as the unusual recessed stonework where the left-hand apse meets the south wall.

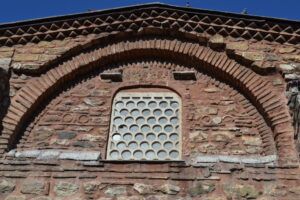

This view shows how much the stonework has changed. The window extended further down. The partial arch at top left shows that there was once a similar window to the left. It was probably bricked over when the minaret was added in the conversion to a mosque. Many of the original windows are now covered. This church must have been much brighter inside in the 10th century.

This brickwork has some interesting features. The nice roofline is Byzantine but some Byzantine flourishes survive on either side of the window.

This is a domed-cross church, a precursor of the. four-column church that became popular later. Van Millingen tells us that the piers and dome arches are original.

This view of what would be the northern side of a conventional east-west oriented church shows the Byzantine wall (on the right) of a narthex. The remainder of the narthex has been replaced by a wooden structure.

The Byzantine well still exists and feeds the modern şadırvan, the descendant of the ayazma.

« Previous Entries Next Entries »