This is just across the road and up the hill from Odalar Camii and probably belongs to the same monastery, which might have been the Monastery of St John in Petra. It burned down in a fire in the early 20th century. It is a solid-looking rectangular block and probably not a church, but another building from the monastery. I couldn’t get in and was taking a photo over the high wall when an efficient woman came out of an apartment block, led me back to the door and showed me how to pick the lock (41.028757,28.939528).

Immediately to the south of the building is a Byzantine cistern. Freely (1983) was dismissive of Kasım Ağa Mescidi itself, which apparently was a ‘very mean hovel’ in the ruins. However, he commented on the beauty of the cistern (İpek Bodrum) with its Corinthian column capitals. The cistern is now inaccessible (at least, I can’t get in) and the roof is occupied by a playground off Kurtağa Çeşmesi Sokak.

Freely, John (1983) Blue Guide: Istanbul. London: Ernest Benn, New York: W.W. Norton

Mamboury, Ernest (1925) Constantinople: Tourists’ Guide, 1st edition. Rizzo and Son, Constantinople.

Matthews, Thomas (2001): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Available at http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/

Müller-Weiner, Wolfgang (1977) Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut) Verlag Ernst Wasmuth Tübingen

Van Millingen, Alexander (1912): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Available at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

[See below for new details of Odalar Camii]

Not much left of this now. Behind the Cistern of Aetius, the wall between numbers 18 and 20 Müftü Sokak is a ramshackle Byzantine thing with identifiable bits of marble sculpture and some hefty buttresses.

While I was photographing this, the kids in number 20 went to get a woman who let me into the yard at the back. This contains some arches, masonry and holes to fall into, all that remains of a once great monastery. (41.029119,28.939933)

The old church has resurfaced. As of May 2017, the residents have been cleared out and the Byzantine walls are clear of the more recent brickwork.

Work started in about February and the demolitionists have done a reasonable job of leaving the church walls intact. Nobody in the area seems to know the plan for the building. They fear that it will become a rubbish dump, a realistic fear as the building rubble on the site is disappearing beneath daily deliveries of household waste.

According to Muller-Weiner (1977), the church now visible is built on a substructure from an earlier church. The dedication of this church is the subject of an academic battle based on threadbare evidence and into which I am not qualified to contribute. This substructure is said to contain 16 rooms. Some sources suggest that these underground rooms (Turkish odalar) are the source of the common name of the mosque. Another suggested origin of the name is the mosque’s proximity to Janissary barracks, built in the late 18th century.

The last real examination of the basement was done in about 1935 after the dome had fallen in but the superstructure of church was mostly intact. This was wrecked in the fire of 1919, after which the land and walls were fair game for anyone who wanted to put up a quick house.

The existing church is arranged roughly along a west-east axis. There are three naves in this cross-in-square structure. The centre is by far the largest. The wall that was previously the most visible part of the building is the boundary between the centre nave and the narrow northern one. Things are not so clear in the southern section. A small piece of the southern wall of the diaconicon is visible, but is not in line with any existing nave wall. It appears that some reconstructions (probably during the building’s time as a mosque) removed most of the southern nave.

The western wall is the best preserved and still supports some houses on Kasim Odalar Sokak. The wall contains some nice arches and illustrates the recessed brick technique that is the main reason for dating this church to the end of the 12th century. Westphalen (1998), in the most comprehensive published survey of the church, thinks this church may have looked similar to Eski Imaret Camii in its prime.

Details of a narthex are obscured by the houses that are still tucked under the western wall of the naos. There is clearly a great deal to see under the ground in this area.

It appears that the church was not converted to a mosque until some time after the 1453 conquest. The Ottomans conquered Kaffa (a Genoese colony in the Crimea) and immediately moved the potentially rebellious Latins to this area of Constantinople. The area also contains Kefeli Camii. This was named after the immigrants from Kaffa. At this point, Odalar Camii appears to have been called St Mary of Constantinople. The inhabitants do not appear to have settled to the satisfaction of their rulers and in 1636, the Christians were booted out to Galata and the decrepit building was converted to a mosque.

It will be interesting to see what happens to the building now it has been cleared. It is a little close to the existing Kasim Aga Camii to be rebuilt as another mosque but that is a likely fate.

The site has been left since about March 2017 and I will keep an eye on it.

By July 2019, someone had built a dwelling in Odalar Camii.

Maybe the urban renewal has stalled for the time being.

Vitalien, Laurent. Travaux archéologiques à Constantinople en 1935. In: Échos d’Orient, tome 35, n°181, 1936. pp. 97-111;

doi : https://doi.org/10.3406/rebyz.1936.2860

https://www.persee.fr/doc/rebyz_1146-9447_1936_num_35_181_2860

Westphalen, Stephan. Die Odalar Camii in Istanbul. Architektur und Malerei einer mittelbyzantinischen Kirche (Istanbuler Mitteilungen, Beiheft 42), Emst Wasmuth Verlag, Tübingen 1998, XIV + 162 σελ., 40 πίνακες, 4°.

https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/makedonika/article/viewFile/5704/5443.pdf

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This undistinguished but pleasant building lies in the maze of streets behind the cistern of Aetius, the sunken football ground and park near Edirnekap (41.029364,28.941481). There seems to be some agreement that it is probably the remains of the refectory of the monastery of St John in Petra, because it’s sort of in the right place and because it doesn’t look like a church. It is very close to the Odalar Camii (Monastery of the Blessed Virgin Mary) and they may have been parts of the same establishment.

Anyway, the outside looks nice with those alternating stone and brick layers. The minaret was restored in 1970 and the rest of the building had a wash and brush-up in 1989. The taciturn bekçi will let you in, prohibit photography and expect a tip. The ban on photos is not a bad thing because the internal decoration of the mosque is fairly horrible.

As of early 2017, the interior of Kefeli Camii has been redecorated and looks rather pleasant again.

References

Freely, John (1983) Blue Guide: Istanbul. London: Ernest Benn, New York: W.W. Norton

Mamboury, Ernest (1925) Constantinople: Tourists’ Guide, 1st edition. Rizzo and Son, Constantinople.

Matthews, Thomas (2001): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Available athttp://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/

Müller-Weiner, Wolfgang (1977) Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut) Verlag Ernst Wasmuth Tübingen

Van Millingen, Alexander (1912): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Available at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is a picturesque church with a strange, rambling shape because of the many additions and modifications it has endured. It has a multiplicity of domes of different sizes, which gives it something of a fairytale appearance.

Unlike most of the other major churches in the district, it is hard to find by simply bumbling around. It is at the end of Fethiye Kapısı Sokak, a turn-off from Fethiye Caddesi downhill from the Selimiye. (41.02881,28.946164). The larger part of the existing building is once more in use as a rather austere mosque. It is always open, unlike the museum part which is closed on Wednesdays. The museum is the parekklesion, or side chapel, that houses the mosaics, far less extensive than in Kariye but just as lovely.

Mamboury suggests that the church was built in the 8th century but adds that the original church is hard to recognise. So much so that most archaeologists date its foundation to the 11th or 12th century. This refers to the older church that is now a mosque. The parekklesion was added to the south of the church in the 13th century as a memorial chapel to one of Andronikus II’s generals. The richness of the shrine gives some idea of how lucrative being a general must have been.

This church was the Patriarchate for a while. The great Patriarch Gennadius, who was apparently consulted on matters of theology by the conquering Sultan Mehmet, moved his HQ here in 1456 from the decrepit Church of the Holy Apostles, the site of which was required by Fatih for his fabulous new mosque. In about 1586, Sultan Murat III decided that this church too was to become a mosque so the patriarchate moved down the hill to the Church of Theotokos Paramythia (Vlach Saray). The conversion to a mosque resulted in the walls between separate buildings and chambers being knocked down and a sort of triangular bit being built on to enable a mihrab to face Mecca. This made a much more open structure but created a puzzle for the Byzantine Institute in their preparation for the restoration in 1949.

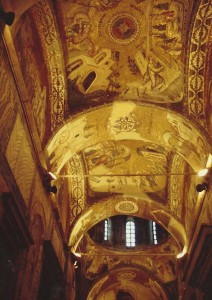

The mosaics were considered by Mamboury to be superior to those in Kariye. There are traces of frescoes remaining but these have largely been destroyed in the various remodellings that the building has endured.

Only one mosaic remains from what appears to have been a life-of-Christ series similar to the example in Kariye. This displays the baptism of Christ in a slightly surprising full-frontal format.

In the arches and small domes on the south side of the church are portrait mosaics of saints, including a fine one of Gregory the Illuminator, driving force behind the Armenian church.

In the semi-dome of the apse is a lovely mosaic of Christ Hyperagathos, said by Freely to mean ‘all-loving’ but more commonly interpreted, as in the Dumbarton Oaks literature on the church, as ‘supremely good’. This appears to be an attempt to depict the concept of John Scotius Eriugena’s 9th century concept of ‘more than goodness‘. This masterpiece is flanked by full-length representations of John the Baptist and Mary, the Theotokos Pammakaristos to whom the main church was dedicated.

In the dome is the traditional Christ Pantocrator (the all-powerful), in this example surrounded by twelve prophets of the Old Testament – Moses, Jeremiah, Zephaniah, Micah, Joel, Zechariah, Obadiah, Habbakuk, Jonah, Malachi, Ezekiel and Isaiah. Some interesting choices in that list.

The mosaics that remain are marvellous in their own right but give a tantalising glimpse of what must have been a magnificent work of art in its totality.

There is a long inscription of a dedicatory poem by Manuel Philes, both on both the inside and outside of the church. Van Millingen provides a translation of this in his definitive 1912 work on Byzantine churches. He also provides some pictures of the church before the Dumbarton Oaks restoration.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is the gem of Istanbul. (41.031327, 28.939184) If you see only one thing from ancient Constantinople, let it be this. My two-year-old daughter is entranced by the glory of the mosaics and the clarity of the imagery. I’m just gobsmacked that such fabulousness has survived through such adversity.

Unfortunately, the nave is closed for restoration in December 2015. There are only a couple of mosaics in there but they are particularly nice. You also miss out on seeing the lovely marble of the main part of the church. The great mosaics and frescoes in the narthex are still accessible.

Van Millingen’s exhaustive investigations led him to the conclusion that a church existed on this site late in the 3rd Century. This was apparently a sort of martyrium, being the burial place of the remains of Babylos of Antioch and his followers. The story goes that Babylos refused the Roman emperor Numerian (Diocletian’s predecessor) entry to his church and was detained, dying in prison as a result of torture. According to Syndicus (1962), this was the first example of translation of the relics of a saint from the site of martyrdom to a church elsewhere. However, Babylas died in Nicomedia (the present-day Izmit) in 298 and his remains were in Daphne, near Antioch (Antakya) by 351. He can’t have stayed in Chora for very long. However, he had returned in the 9th century. His relics appear to have been well-travelled.

The church is traditionally known as a part of the Monastery of St Saviour in the Chora. The meaning of Chora (Χώρα) has been the subject of much debate as its general meaning of ‘region’ spans a spectrum from country (as in a rural area outside a city’s walls) through to Basileia (βασιλεία) the kingdom of an Emperor or the higher sphere of the Kingdom of God. Some scholars, such as van Millingen (1912), believe that the monastery was named after the higher kingdom of God. Others, such as Mamboury (1924), incline toward the idea that Chora referred to being in the rural hinterland in the way that the Church of St Martin in the Fields in London once meant but clearly isn’t applicable now.

The church is obviously within the current walls, built in the time of Theodosius in the early 5th century. However, any building established on the current site of the Chora before then would have been outside the walls of Constantine. Mamboury cites evidence that Justinian (527-565) restored a church here but the simple basilica that appears to have resulted from this was insufficiently notable to be recorded in Procopius’s Buildings, that paean to the bricks-and-mortar glories of Justinian.

The church was the burial place in 740 of the learned Patriarch Germanus. He had been an opponent of Emperor Leo III’s iconoclasm and as such, the Chora became a rallying place for those who still incorporated ikons in their worship. The monastery and the monks thus became a target for the hatred of Leo’s son, Constantine Copronymus (Constantine, whose name is shit), possibly not a name the use of which the emperor encouraged. Any interior decoration that had been in the church at this time would have disappeared then. The church failed to align itself with the winning sides of several subsequent disputes with the result that the place was in a sad state as the 11th century dawned.

So the current church seems to have come about in the late 11th Century, restored (according to Mamboury) or founded (according to Freely, 1983) by Mary Doucas, a very well-connected lady who connected the courts of the Bulgars and the Byzantines by marriage. Her church had some interesting structural instabilities which resulted in the need for the apses to be rebuilt in the 12th century.

Enter Theodore Metochius, a renaissance man in the court of Emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus. In 1321, he completed his dazzling reconstruction of the Church of St Saviour in the Chora, much of which is still present. Metochius had accumulated immense riches in his passage up the ziggurat of Byzantine power. The only way for a devout citizen of Constantinople to display such enormous wealth was to build the greatest gallery of late Byzantine art that existed in the city.

Due to the accumulation of stonework of various ages in the structure of the church there is dispute over whether Metochius built or reconstructed the two narthexes and the parekklesion, but it is in these areas outside the significantly older nave that he concentrated the glory of his pictorial Bible.

The exonarthex is the gallery for a sequence of the life of Mary and the early life of Christ. There are a good few pieces of the mosaic decoration missing, but the 19 scenes of the lives of Mary and Jesus are beautiful. The exterior narthex includes the southwest room at the entrance to the parekklesion. This room holds a particularly lovely non-representational dome decoration and in the lunettes below is depicted, with notable savagery, the massacre of Herod.

The lunette over the central doorway leading to the inner narthex has a large mosaic of the Pantocrator bearing the inscription: IC HC. I ΧΩΡΑ ΤΩN ZΩΝΤΩΝ (Jesous Christos en chora ton zondon). My translation of this, with the obvious influence of the King James, is “Jesus Christ: The kingdom in which we dwell.” The stumbling block in a successful interpretation is that tricky word Χώρα. So good luck with that.

Pantocrator with the ambiguous inscription: IC HC. I ΧΩΡΑ ΤΩN ZΩΝΤΩ. Water into wine and loaves and fishes above.

The interior narthex continues the mosaic cycle of the deeds of Christ. This is a lovely room with the glorious decorations of the domes at the south and the north. From the height of the south dome glowers a particularly fine Christ Pantocrator flanked by 39 of his ancestors, including such dignitaries as Adam, Noah, Abraham, Jacob and Joseph (of dreamcoat fame).

The north dome hosts a stylised Theotokos with a luminous Christ child. Around the dome are various kings of the House of David and other prominent inhabitants of the Old Testament who have been claimed by miscellaneous scholars to be indirect ancestors of Christ.

North dome of the inner narthex. Theotokos flanked by David, Solomon, Moses, Job and many other worthies.

The mosaics of the inner narthex depict Christ healing a bewildering array of ailments, culminating in the splendid ‘Christ healing a multitude afflicted with various diseases’ executed after the artist had run out of specific text references.

Most of the nave is coated with lovely matched marble panels but there are a couple of fine mosaics. As with most Byzantine churches, the nave is surprisingly small for such a prominent religious establishment – about the size of the average classroom. There is a partially restored Mary Hodegetria on the right as you enter. This has a finely wrought face and another reference to Χώρα as the ‘dwelling place of the uncontainable’. For me, this is evidence that the Chora in the Monastery’s title referred to the Kingdom of God rather than some idea of the place being out in the sticks.

And the parekklesion. Heaven and hell, life, death, judgement, resurrection and eternal consequences. All done in fresco worthy of Leonardo. The dome has another Theotokos, a subject that seems far more suited to the medium of fresco than mosaic. The facial detail is particularly expressive. Beneath Mary in heaven is the court of angels and below this is Jacob’s ladder, the Miroesque pathway of hope to the celestial hemisphere.

For details of each picture, go to John Freely’s incomparable 1983 Blue Guide. It’s out of print so if you can’t find it, here’s a link to van Millingen’s description from 1912.

The Church of the Chora had a pretty bloody time of it in 1453. It was close to the walls so the sacred ikon of Mary Hodegetria was brought from its monastery close to the sea walls and placed in the zone of greatest peril, in the Chora. The church was one of the first places to be overrun by the forces of Fatih Sultan Mehmet. The ikon disappeared forever and the church suffered greatly. It languished in dereliction for decades until the Vizier Atık Ali Paşa restored it as a mosque. It may be to this great eunuch that we are indebted for the current presence of the church’s decoration. Rather than scouring the glittering decoration from the vaults and domes, he had them covered in a sober coat of whitewash, thus preserving them until 1860, when Pelopidas Kouppas, a Greek architect, rediscovered them in the partially collapsed building. The results of the subsequent partial restoration are visible in van Millingen’s illustrations from 1912.

What we see now is the product of the restoration by the Byzantine Institute of America that began in 1947. The hero of this project is Carroll Fenton Wales who entered the programme in 1952 and brought scholarship, artistic sensitivity and an obsession with the craft of the Byzantine mosaicist. His work is the reason that we are able to see such a gorgeous monument to Byzantine grandiosity and Christian artistry.

The Monastery of the Chora appears to have had a particular significance to the forces of Mehmet II as they conquered the city. This scene from the 1453 Panorama museum constructed in 2009 shows the Chora in unrealistic proximity to the walls. This is understandable that the artist would make the church so clear because the ikon of Mary Hodegetria which was kept there during the siege was seen as the symbol of Constantinople’s immortality. Fatih’s troops headed straight there and the symbol, and Constantinople’s Christian primacy, were destroyed..

« Previous Entries Next Entries »