My favourite little Byzantine thing. This is a lovely church, ideally proportioned and of a red colour that catches the sun attractively. The inexorable rise of Istanbul’s pavements over the centuries has sunk it a little but this church was never about grandeur. The curmudgeonly Robert Liddell (p82), while admitting that this was a ‘well-proportioned’ church, grumbled that it was not worth making the effort to get through the maze of streets to find it. I admit that I don’t quite know the way there but I always seem to find it if I walk uphill from Atatürk Bulvarı and past the great mass of Zeyrek Camii. There’s a Gertrude Bell picture from 1905 that shows the Eski Imaret in wide open fields.

Pantepoptes (the all-seeing) seems to have been founded in about 1080 by the powerful Anna Dedalassenes, who retired to her convent for the last few years of her life. The church once contained one of the nails of the true cross and some spiky bits from the crown of thorns, but so many of these seem to exist that there must have been a factory in the Holy Land churning them out to meet demand in the early Byzantine period. The 1204 Venetian conquest meant that the relics went to Venice and the church was taken for the Latin rite until the status quo was re-established in 1261.

All of this may be true but comparatively recent studies cast doubt on the accepted view that Eski Imaret Camii was once the Monastery of St Saviour Pantepoptes. Cyril Mango is elegantly dismissive of the conjecture that has led to the association of this building with the identity of Pantepoptes that Freely and Mamboury have accepted as fact, as did I until I read Mango’s rather simple but comprehensive argument.

The idea of Pantepoptes as ‘all-seeing’ was apparently linked to its elevated position which provided an unparalleled view of traffic in the Golden Horn. During the 1204 Latin siege, Emperor Alexios V watched the depressing spectacle of the invasion fleet dropping anchor near the Blachernae Palace from the heights of the Pantepoptes Monastery. Unfortunately, the view from the Eski Imaret, even in the days before tall housing surrounded it, never extended as far up the Golden Horn as Blachernae. This contour map illustrates this point. There is a lot more to Mango’s argument and it can be read here. He places the Monastery of Christ Pantepoptes on the site of the current Yavuz Sultan Selim Camii. The redoubtable Professor Neslihan Asutay-Effenberger suggests that Eski Imaret Camii may have begun life in the early 10th century as a Church of St Constantine. If so, it was heavily modified as Marinis reports that the current building conforms in architectural style to the late 11th and early 12 centuries.

Whatever it was, it is now the prettiest thing in Istanbul. The external brickwork has playful little surprises all over it and the tiled helmet on the dome is like an inverted buttercup. Fikret Çuhadaroglu, the architect in charge of the restoration in 1970 clearly had a fondness for parochial Greek churches and their idiosyncratic flourishes.

It’s a medrese at the moment, a haven of devout masculine study, but they don’t seem to mind when I take my little daughter in there. A bit of giggling amongst the verses and then it’s back to work. I suppose they’re used to us by now. (41.021622,28.954811)

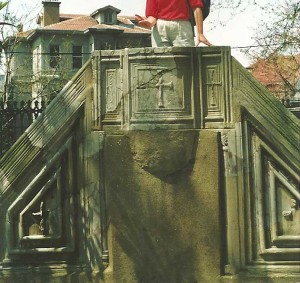

This is what remains of the minaret of the Eski Imaret Camii.

Dome and west side of nave

In summer 2019, a new restoration is in full swing.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

There was no Armenian Patriarchate in Constantinople in Byzantine times. The Council of Chalcedon in 451 had rendered heretical the miaphysite belief of the Oriental Orthodox Churches (Armenian, Syriac, Coptic, Ethiopian among others). Miaphysitism means that the divinity and the humanity of Christ are united in one nature as opposed to the Dyophysite position of the Eastern Orthodox Churches (and the Romans at this time) which held that the divine and the human represented two natures of Jesus Christ in the one person. Trivial to some, but a vital theological point that led to a major separation of the church.

After his 1453 conquest of Constantinople, Fatih Sultan Mehmet asked the Armenian community to establish a church. According to the Millet system, religious groups had a certain degree of self-rule under the Ottoman Empire. In 1461, Hovakim I became the first Armenian Patriarch in Constantinople. The Patriarchate was in charge of all Armenians, including the Catholics as well as, for a while, the Syriac Orthodox Church. The Ottomans were only interested in administrative practicality. Interestingly, it was the Turkish Foreign Minister who visited the Patriarchate in 2012 to hear allegations of discrimination against Armenians. This seems to be a remnant of the Millet system in which religious and ethnic minorities are dealt with as something other than Turks although the party line is that all citizens of Turkey are Turks and that foreigners are things that are firmly outside the borders.

The Patriarchate moved to its current, rather nice, site at Kumkapı (41.004613,28.960948) in 1641. Patriarch Madteos III was exiled for protesting to Sultan AbdulHamid about the appropriately named Hamidian massacres of 1895. Armenian patriarchs have had rather a melancholy time ever since. There is a lot more detail on the Patriarchate website. The Patriarchate does not permit photography on the grounds of its churches.

The Mother See of the Armenian Church is in Echmiadzin (Vagharsharpat), not too far from Yerevan.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is the story of a complete waste of time. Paspates made a lithograph of a pretty octagonal mescit in the Laleli area in the 1870s. Van Millingen argued over the purpose of the building in Byzantine times and concluded that it was probably a funeral chapel. Whatever it was, the municipality decided that the demands of city planning meant that it had to go and they would build the shopping street of Harikzedelar Sokak over the remains.

The TAY website places the location of the building at around A on the map but also points out some Byzantine remains in the basement of nearby Adem İşhane (B). Eminönü Belediyesi’s official map of mosque locations places it at C. There was a car park here, often a useful way of keeping a space open so foundations can be seen, but there were none.

Adem İşhane is no longer there – it has been split into individual shops. The people in the basement shop had heard of the remains but except for the entrance, their shop was bounded on all sides by 21st century concrete. They suggested trying to approach from the street behind. Here, there was an enormous building site. The workers raised no objection to me going into the basement, four floors of sealed concrete. Maybe if I had come three months earlier, I would have witnessed the edifying spectacle of a man with a pneumatic drill blasting thousand-year-old masonry into dust.

I spent more time looking for nothing than I would have exploring an intact church. Still, there are some fragmentary remains in the Archaeological Museum. These bits in the grounds of nearby Laleli Camii might be from the Balaban Ağa Mescidisi. Or they might not.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Excavations in the mid twentieth century during the construction of buildings for Istanbul University (41.013171,28.959398 or thereabouts) revealed traces of several churches. These have now been covered up except for some pieces that were removed and placed in the Archaeological Museum. The churches are now known as Basilica A, B, C and D. The most substantial remains are a marble pulpit from Basilica A that stands in the grounds of Aya Sofya and some column capitals, some of which are scattered about the grounds of the university close to the fire tower.

Part of narthex of Church A, unearthed by excavations for Vezneciler Metro station, cut up and moved to this location (41.011786, 28.959822) by crane

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Excavations in Saraçhane for the Şehzadebaşı intersection in 1960 revealed the remains of a massive Byzantine church (41.014062,28.952971). Bigger than the Sülemaniye Camii, it was a basilica dedicated to St Polyeuktos. It has fallen a long way since its heyday in the sixth century. These days, it is the sort of public toilet in which George Michael may feel rather out of his depth. The razor wire and the locking up at night do not prevent the diurnal sleaze and defaecatory activity. When I was there, a man faced deep into a niche for at least twenty minutes, clutching an intimate portion of his anatomy. Don’t take the children.

There is one thing that can be said for the 1204 sack of Constantinople by the barbarians of the fourth crusade – it preserved some lovely pieces from the Church of St Polyeuktos. These can be seen in the vicinity of the Basilica San Marco in Venice. The pillars of Acre don’t come from Acre, they come from this church. The vandals who stole the porphyry sculpture referred to as The Tetrarch left a foot behind. This was dug up in 1960 and matched the missing limb from the statue in Venice.

« Previous Entries