During the 1204 siege and eventual sack of Constantinople by the Christian vandals, the Empire of Trebizond was formed by Alexios and David, rebellious grandsons of the Byzantine Emperor Andronikos Komnenos. Trebizond, together with Nicaea and the Despotate of Epirus entered a power struggle to vie for what was left of the Byzantine Empire. The rulers of all three states called themselves ‘Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans’. The Aya Sofya (41.002419,39.695642), a gorgeous church that shows the influence of Selçuk architecture, was built between 1238 and 1263 as the centrepiece of what was planned to be the new empire. The reconquest of Constantinople by the kingdom of Nicaea put an end to that particular squabble although Trebizond was always uncomfortable between powerful and avaricious neighbours. Despite a period of adroit diplomacy based on a tactic of marrying allegedly beautiful daughters to potential allies, the Ottomans finished off the Empire of Trebizond in 1461, 8 years after they had taken Constantinople.

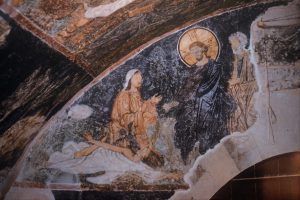

In summer 2016, Koc University held an exhibition on Ayasofya, its frescos and the general religious atmosphere of the place when outsiders began to study it in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It brought together a great many objects and images and provided a serious academic view of Trebizond and its legacy.

Posted June 25, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Iznik’s Aya Sofya is the centre of town. This was the Patriarchal Church during the occupation of Constantinople and the centre of an Ecumenical Council in 787. This was during the great battle between iconoclasm and orthodoxy. The Seventh Ecumenical Council had been convened by the iconoclast Emperor Constantine V in his palace at Hieria on the Asian side opposite Constantinople in 754. This was a dark period in church history. The Patriarchates of Antioch, Alexandria and Jerusalem were occupied by Islamic rule. Rome, with its support of Christian imagery, was not invited to take part. Anastasios, the Patriarch of Constantinople, whose support for iconoclasm had only been obtained when emperor whipped, blinded and paraded him through the streets in shame, had finally died. Constantine V took the opportunity of institutionalising iconoclasm by calling in a convocation of bishops that he knew he could control.

Unsurprisingly, the inevitable ruling of this Council was not accepted by the mainstream of the church. By 786, the position of Patriarch had regained something of its former power. The new Patriarch, Tarasius, wished to re-establish links with the other churches and a new Council was convened in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. The Roman Pope sent representation and it seemed inevitable that iconoclasm would be defeated until military units disrupted the proceedings, demanding a return to the dictates of the emperor.

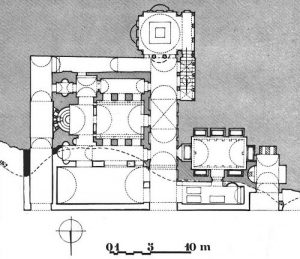

Some subterfuge in the shape of a hastily contrived campaign appears to have diverted the agitators and the Council was relocated to Nicaea. The Church of the Holy Wisdom (Agia Sophia) was the centre of proceedings. This was built in the 6th century on the orders of Justinian I at around the same time as the Agia Sophia in Constantinople. The shape of the present church may come from an 11th century reconstruction following the inevitable earthquake. It is a basilica with a central nave along an east-west axis and smaller aisles either side. The wide nave ends in an apse with a synthronon, a set of semicircular steps for members of the clergy. There is a single narthex inside the entrance on the western side. The domes atop the eastern ends of the two outer aisles were built in either the 11th or 13th century and were once above chapels separate from the rest of the church. There is some doubt that the existing building named Aya Sofya is the Church of Agia Sophia in which the 7th Ecumenical Council was held. One objection is that it was too small to contain the crowd of more than 300 bishops and their entourages. More can be read about this here.

In any case, it was in Nicaea that a halt to iconoclasm was called. However, the iconoclastic faction remained influential and the Emperor once again outlawed the making and veneration of icons in 815. The Seventh Ecumenical Council (Second Council of Nicaea in 787) is the last of the councils to be recognised by both the Eastern and Western Christian churches. The schism finally became official in the eleventh century.

With the Fourth Crusade rather emphatically ending the reign of Constantinople as the centre of the Orthodox Church, nominal patriarchates sprang up in three splinter states: the Empire of Nicaea, the Empire of Trebizond and the fabulously named Despotate of Epirus. History records Nicaea (Iznik) as having the most legitimate claim as this is where the Byzantine Emperor Theodore Lascaris took refuge and rebuilt his power base. Michael VII Paleologus of Nicaea rebounded and retook Constantinople in 1261, ending the debate about which political entity was the legitimate successor to Constantinople.

When I visited Iznik in 1990, Aya Sofya was a lovely ruin. Now it is a different building, a sort of government mosque placed uncomfortably inside an unsympathetically restored relic. The restoration will ultimately increase the survival potential of the remains. It’s just a bit concrete-and-plastic. (40.429203,29.719938)

The thirteenth century flowering of Nicaea as the home of the exiled Patriarchate led to the construction of a number of churches and the repair of existing ones. However, after Ottoman conquest, the city of Iznik was impoverished and underpopulated. The churches gradually became more and more dilapidated until the Turkish War of Independence. Iznik was in the path of the Turkish Army which, scenting victory, drove the hapless Greek population towards the Aegean coast. Iznik, having a large Christian presence, was a target. All churches were destroyed with the exception of Aya Sofya, which had been converted into a mosque.

Posted June 25, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is only two hours from Istanbul, which is some people’s daily commute. In the lovely seaside town of Kıyıköy, on the bank of one of its two rivers, is the amazing Monastery of St Nicholas (41.634077,28.084456). It is cut into the rock, as are the churches in Cappadocia, but this rock is far more resistant. When one approaches, a set of arches appears in the cliff face. A man sits in a wooden chair, reading a newspaper. There is nobody else around. The man does not look up until addressed. He offers the use of a torch. Enquiries as to admission price are met with a laconic, ‘You may pay something if you like’. This article is about the bekçi (caretaker).

It is not like Cappadocia. The interior is cool and damp. The rock surfaces are covered with algae. The only graffiti consists of the algae being scratched away to form letters that do not seem to damage the rock. The tunnels are intricate and extensive. The churches are identifiably Byzantine but not made from masonry and carved blocks – it’s all hewn into the rock itself. An amazing place. It appears to have been built in the mid-sixth century, during the reign of Justinian. Apparently it resurfaced in the 1950s after floodwaters exposed the tunnels under the cliffs (Kassabova, 2017).

There was once a wooden porch outside that extended the uneven rock frontage to provide a sense of order. The nature of the rock means that entrance to the monastery is from the south. The main church is aligned in the customary east-west direction.It is a rather lovely three-naved building with the remains of a carved iconostasis and an impressive synthronon in the sanctuary.

A narthex leads along the western side of the church deep into the mountain wherein lies the ayazma. The narthex has some lovely carving and an impressive barrel-vaulted ceiling.

The ayazma is the real treasure. It is a four-column, domed, trefoil arrangement over a shallow (and cold) pool. Swallows nest on the walls and startle one as they dart past one’s ears in the dark.

The whole south-facing rock wall is hollow with monastic cells and tiny chapels. One can keep going eastward from the main entrance and continue finding bits of monastery. There is a cold spring with really nice water a few metres up on the right.

There is a lot of remaining Byzantine stuff around here. A big cave above the Kazandere River (41.619838,28.097556)has seen some Christian activity. Around the village of Balkaya (41.613196,27.96175) are some cave churches and another rock-cut monastery. The town of Vize 41.576263,27.767526) has everything from a Megalithic place of worship to a 6th century Byzantine church, inevitably called Ayasofya.

Atmaca, B. (2011) Aya Nikola Manastırı. Kıyıköy. Available online at: http://www.kiyikoy.gen.tr/kiyikoy-manastiri Accessed 25th Jan 2017

Civelik, E. (2016) Aya Nikola Manastırı. Kırklareli Kültür Varlıkları Envanteri. Available online at: http://www.kirklarelienvanteri.gov.tr/anitlar.php?id=80 Accessed 24th Jan 2017

Kassabova, K. (2017) Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe. Granta. Partially available online at: https://books.google.com.tr/books/about/Border.html?id=owskDgAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y Retrieved 14 Oct 2017

Yeni Haber (2018) Aya Nikola Manastırı’nın 40 yıllık gönüllü bekçisi. Available online at: https://www.haberturk.com/aya-nikola-manastiri-nin-40-yillik-gonullu-bekcisi-2177380/3 Retrieved 8th Feb 2019

Posted June 25, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Posted June 25, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

« Previous Entries Next Entries »