Bakırköy is inextricably linked in Istanbul’s collective mind with the presence of a psychiatric hospital but was a desirable residential seaside location throughout most of the twentieth century. Long before that, it was a thriving Byzantine suburb seven (hebdomon means seventh) miles from the Milion, the marker of the centre of Constantinople. Ebuzzıya Caddesi turns out to be a pleasant shopping street with an Armenian and a Greek church (41.977345,28.874812). The Greek one is the successor to a Byzantine Church of St John the Evangelist. There was uproar a few years ago when a road-widening meant that the narthex of this church was demolished. Its place is now (2014) taken by a rather nasty littl e wooden structure. Still, go ahead and light a candle.

The much larger Church of John the Baptist was in a location (40.979215, 28.882061) now on Istanbul Caddesi. Here, the hand and occipital bone of the Christener of Christ were once kept, despite the existence elsewhere of several intact heads of the saint. Umberto Eco made much sport of the proliferation of Baptist heads in his novel Baudolino. The relics from the Church of John the Baptist are now in Topkapı Sarayı, displayed with appropriate solemnity.

This was the church in which Byzantine emperors were crowned before entering the city in triumph through the Golden Gate. Mamboury reported that significant remains of the church were visible in the 1950s. These disappeared underneath housing. The octagonal Byzantine church of St John the Baptist was discovered when the site of the SSK hospital (41.979183,28.881252) was being excavated. However, the hospital is not terribly photogenic.

This picture shows the remains of the Church of John the Baptist in 1960, just before they were destroyed to build the SSK Çocuk Hastanesi on Istanbul Caddesi.

Campus Tribunalis was a military complex built in the 4th century by Emperor Valentinian I. It served as the mustering ground for troops before and after campaigns in Thrace and beyond. It was famously extravagant for an army barracks and had swimming pools, baths and churches. Now it is an industrial zone and site of the Veliefendi Hippodrome, which charges 2 lira for men and 1 lira for women to watch horse races. There is one remaining Byzantine wall (40.981580, 28.885616) which is now part of a police parking area for impounded cars. Until a few years ago there was a small but intact Byzantine building near the police karakol. Now, like the karakol, it is gone. Massive building work in 2015 threatens the few remaining Byzantine stones.

A section of Byzantine foundations (40.981147, 28.886185) has been preserved among the construction. The security staff told me that it was the Hebdomon Palace but they wouldn’t let me in to see. I had to take photos over the fence.

In the Bakırköy area, the major Byzantine sites seem to have hospitals built on them. For Campus Tribunalis, the medical successor is Kızılay Ahmet Bahadırlı Tıp Merkezi, on the coast road. In the excavations to build the foundations for the hospital, a number of ecclesiastical-looking architectural fragments were unearthed. These are now on display in an area of the garden where nobody goes (40.979188, 28.886262). One of these fragments is grandly called a Roman Mortarium in the literature. Slightly disappointingly, this turns out to be a dished stone used for grinding grains and herbs.

Fifth century capital and mortarium

Another hospital, Bakırköy Akıl ve Sinir Hastalıkları Hastanesi was built over a Byzantine hypogeum, a sort of subterranean church built as a cemetery. Some remnants are in a circular park in the centre of the hospital grounds (40.991168, 28.862196). They include a bathtub sarcophagus and some 6th century column capitals. The remains of the hypogeum itself seem to be popular with parkour enthusiasts.

The hypogeum was rediscovered in 1914 during construction work for barracks at the start of World War I. After the war, the French occupying troops were pressed into service as excavators. The triumph of the Turkish republicans meant the exit of the French in 1923, leaving the investigation unfinished. I am not sure that any real archaeological work has been done since. The site has almost disappeared again but the basic structure is still discernible.

It is a 5th century circular building, shaped into a cross by four naves. The resulting quarters formed pillars that supported a dome. In the opposite walls of each pillar were arched tombs for a sarcophagus. Around the outside of the whole structure was a narrow circular passage, still accessible and in good condition. Sarcophagi were found in six of the eight niches. One was claimed to be that of Emperor Basil II, something of a hero to the recently victorious Turks. Basil ruled from 976 to 1025 and defeated the Bulgarian forces who had threatened the area to the west of Constantinople for centuries. By the time the hypogeum was excavated, he was popularly known as the Bulgar-slayer. The time was right for a shrine to a nationalist hero, even though there was no evidence that his body had ever been placed there. The legend of Basil’s burial place, like the site itself, crumbled back into oblivion.

Western nave. Niche at left faces another (under ivy at right). Entrance to circular passage to the right of the tree.

Looking west from the eastern rim of the church. On the left is the north-west pillar. One of the niches can be seen at lower left.

Niche for sarcophagus in north-west pillar, facing onto the western nave. At the back, the passage turns at right angles to form the niche facing the northern nave.

Fildamı Sarnıcı, the massive cistern near Bakırköy where the Sultan allegedly once kept his elephants.

This cistern once provided the water for the Hebdomon area. This part at the south-west corner was a pressure tower where water was allowed to rise from the cistern for distribution.

Part of the cistern near the current entrance. It looks a little like the Church of St Saviour Philanthropes, which is embedded in the sea walls.

View of the north wall of the western entrance to the Martyrion At left is a niche, at right is the brickwork over the ambulatory passage. June 2017

Posted June 25, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

A Victorian oddity with a nice collection of Byzantine stonework acquired from Constantinople in the latter years of the 19th century by lawyers and amateur archaeologists Dr Edwin Freshfield and Sir Henry Cosmo Orne Bosnor. According to the man who let me into the church, Freshfield and Bosnor panted up to their parish church of St Andrew, presented their collection and said, “Look what we have for you”. On finding that their treasures were not wanted there, they engaged Sidney Barnsley to build them a Byzantine church to put them in. It’s a peculiar place – marbled like Aya Sofya, with an apse like a gold-mosaic Aya Irini and with column capitals dotted incongruously within. It has the most marvellous arts-and-crafts ceiling. ‘Eccentric’ is the word to use. (51.269143, -0.211640)

Column capitals from Blachernae Church, Boğdan Sarayı, the Monastery of St John of Studion and the Basilica of St John, Selçuk.

Posted June 25, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is where it all began. Envy of the dome inspired the architects and, more so, the greedy, grasping, exhibitionistic emperors to equal and outdo the glory of the Pantheon. So here it is, not a Byzantine church but the prototype of the Byzantine style. (41.898955,12.476799)

Posted June 25, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

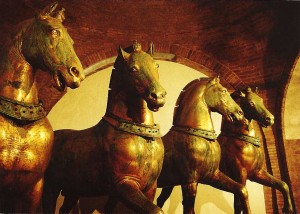

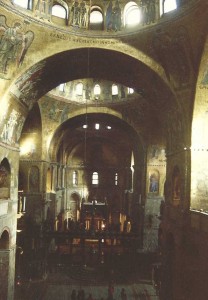

The fourth crusade was largely a Venetian enterprise so it was to here that the Venetian Lion’s share of the spoils came. The quadriga, the four horses that symbolise the power of Constantinople are here both in reality (inside) and in replica (outside, overlooking the Piazza). An educated trawl through the west front of San Marco is like a tour of the nicer bits of Byzantium, so much of it festoons this 13th century addition to the basilica. (45.434403,12.33932) It appears to follow the design pioneered by the Church of the Holy Apostles, once located on the great hill now surmounted by the Fatih Camii.

Posted June 25, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Butrint has had a great deal more history than its residents would ever have desired. It is now in Albania, but has been invaded by, among others, Ottomans, Venetians, Byzantines, Ostrogoths and Napoleon. From 1204, Butrint was part of the Despotate of Epirus, one of the post-Byzantine states vying for neo-Byzantine supremacy after the Latin conquest. To boost its qualifications for being on this site, here are some Byzantine churches. (39.746497,20.023216)

« Previous Entries Next Entries »