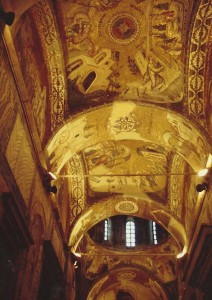

This is the gem of Istanbul. (41.031327, 28.939184) If you see only one thing from ancient Constantinople, let it be this. My two-year-old daughter is entranced by the glory of the mosaics and the clarity of the imagery. I’m just gobsmacked that such fabulousness has survived through such adversity.

Unfortunately, the nave is closed for restoration in December 2015. There are only a couple of mosaics in there but they are particularly nice. You also miss out on seeing the lovely marble of the main part of the church. The great mosaics and frescoes in the narthex are still accessible.

Van Millingen’s exhaustive investigations led him to the conclusion that a church existed on this site late in the 3rd Century. This was apparently a sort of martyrium, being the burial place of the remains of Babylos of Antioch and his followers. The story goes that Babylos refused the Roman emperor Numerian (Diocletian’s predecessor) entry to his church and was detained, dying in prison as a result of torture. According to Syndicus (1962), this was the first example of translation of the relics of a saint from the site of martyrdom to a church elsewhere. However, Babylas died in Nicomedia (the present-day Izmit) in 298 and his remains were in Daphne, near Antioch (Antakya) by 351. He can’t have stayed in Chora for very long. However, he had returned in the 9th century. His relics appear to have been well-travelled.

The church is traditionally known as a part of the Monastery of St Saviour in the Chora. The meaning of Chora (Χώρα) has been the subject of much debate as its general meaning of ‘region’ spans a spectrum from country (as in a rural area outside a city’s walls) through to Basileia (βασιλεία) the kingdom of an Emperor or the higher sphere of the Kingdom of God. Some scholars, such as van Millingen (1912), believe that the monastery was named after the higher kingdom of God. Others, such as Mamboury (1924), incline toward the idea that Chora referred to being in the rural hinterland in the way that the Church of St Martin in the Fields in London once meant but clearly isn’t applicable now.

The church is obviously within the current walls, built in the time of Theodosius in the early 5th century. However, any building established on the current site of the Chora before then would have been outside the walls of Constantine. Mamboury cites evidence that Justinian (527-565) restored a church here but the simple basilica that appears to have resulted from this was insufficiently notable to be recorded in Procopius’s Buildings, that paean to the bricks-and-mortar glories of Justinian.

The church was the burial place in 740 of the learned Patriarch Germanus. He had been an opponent of Emperor Leo III’s iconoclasm and as such, the Chora became a rallying place for those who still incorporated ikons in their worship. The monastery and the monks thus became a target for the hatred of Leo’s son, Constantine Copronymus (Constantine, whose name is shit), possibly not a name the use of which the emperor encouraged. Any interior decoration that had been in the church at this time would have disappeared then. The church failed to align itself with the winning sides of several subsequent disputes with the result that the place was in a sad state as the 11th century dawned.

So the current church seems to have come about in the late 11th Century, restored (according to Mamboury) or founded (according to Freely, 1983) by Mary Doucas, a very well-connected lady who connected the courts of the Bulgars and the Byzantines by marriage. Her church had some interesting structural instabilities which resulted in the need for the apses to be rebuilt in the 12th century.

Enter Theodore Metochius, a renaissance man in the court of Emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus. In 1321, he completed his dazzling reconstruction of the Church of St Saviour in the Chora, much of which is still present. Metochius had accumulated immense riches in his passage up the ziggurat of Byzantine power. The only way for a devout citizen of Constantinople to display such enormous wealth was to build the greatest gallery of late Byzantine art that existed in the city.

Due to the accumulation of stonework of various ages in the structure of the church there is dispute over whether Metochius built or reconstructed the two narthexes and the parekklesion, but it is in these areas outside the significantly older nave that he concentrated the glory of his pictorial Bible.

The exonarthex is the gallery for a sequence of the life of Mary and the early life of Christ. There are a good few pieces of the mosaic decoration missing, but the 19 scenes of the lives of Mary and Jesus are beautiful. The exterior narthex includes the southwest room at the entrance to the parekklesion. This room holds a particularly lovely non-representational dome decoration and in the lunettes below is depicted, with notable savagery, the massacre of Herod.

The lunette over the central doorway leading to the inner narthex has a large mosaic of the Pantocrator bearing the inscription: IC HC. I ΧΩΡΑ ΤΩN ZΩΝΤΩΝ (Jesous Christos en chora ton zondon). My translation of this, with the obvious influence of the King James, is “Jesus Christ: The kingdom in which we dwell.” The stumbling block in a successful interpretation is that tricky word Χώρα. So good luck with that.

Pantocrator with the ambiguous inscription: IC HC. I ΧΩΡΑ ΤΩN ZΩΝΤΩ. Water into wine and loaves and fishes above.

The interior narthex continues the mosaic cycle of the deeds of Christ. This is a lovely room with the glorious decorations of the domes at the south and the north. From the height of the south dome glowers a particularly fine Christ Pantocrator flanked by 39 of his ancestors, including such dignitaries as Adam, Noah, Abraham, Jacob and Joseph (of dreamcoat fame).

The north dome hosts a stylised Theotokos with a luminous Christ child. Around the dome are various kings of the House of David and other prominent inhabitants of the Old Testament who have been claimed by miscellaneous scholars to be indirect ancestors of Christ.

North dome of the inner narthex. Theotokos flanked by David, Solomon, Moses, Job and many other worthies.

The mosaics of the inner narthex depict Christ healing a bewildering array of ailments, culminating in the splendid ‘Christ healing a multitude afflicted with various diseases’ executed after the artist had run out of specific text references.

Most of the nave is coated with lovely matched marble panels but there are a couple of fine mosaics. As with most Byzantine churches, the nave is surprisingly small for such a prominent religious establishment – about the size of the average classroom. There is a partially restored Mary Hodegetria on the right as you enter. This has a finely wrought face and another reference to Χώρα as the ‘dwelling place of the uncontainable’. For me, this is evidence that the Chora in the Monastery’s title referred to the Kingdom of God rather than some idea of the place being out in the sticks.

And the parekklesion. Heaven and hell, life, death, judgement, resurrection and eternal consequences. All done in fresco worthy of Leonardo. The dome has another Theotokos, a subject that seems far more suited to the medium of fresco than mosaic. The facial detail is particularly expressive. Beneath Mary in heaven is the court of angels and below this is Jacob’s ladder, the Miroesque pathway of hope to the celestial hemisphere.

For details of each picture, go to John Freely’s incomparable 1983 Blue Guide. It’s out of print so if you can’t find it, here’s a link to van Millingen’s description from 1912.

The Church of the Chora had a pretty bloody time of it in 1453. It was close to the walls so the sacred ikon of Mary Hodegetria was brought from its monastery close to the sea walls and placed in the zone of greatest peril, in the Chora. The church was one of the first places to be overrun by the forces of Fatih Sultan Mehmet. The ikon disappeared forever and the church suffered greatly. It languished in dereliction for decades until the Vizier Atık Ali Paşa restored it as a mosque. It may be to this great eunuch that we are indebted for the current presence of the church’s decoration. Rather than scouring the glittering decoration from the vaults and domes, he had them covered in a sober coat of whitewash, thus preserving them until 1860, when Pelopidas Kouppas, a Greek architect, rediscovered them in the partially collapsed building. The results of the subsequent partial restoration are visible in van Millingen’s illustrations from 1912.

What we see now is the product of the restoration by the Byzantine Institute of America that began in 1947. The hero of this project is Carroll Fenton Wales who entered the programme in 1952 and brought scholarship, artistic sensitivity and an obsession with the craft of the Byzantine mosaicist. His work is the reason that we are able to see such a gorgeous monument to Byzantine grandiosity and Christian artistry.

The Monastery of the Chora appears to have had a particular significance to the forces of Mehmet II as they conquered the city. This scene from the 1453 Panorama museum constructed in 2009 shows the Chora in unrealistic proximity to the walls. This is understandable that the artist would make the church so clear because the ikon of Mary Hodegetria which was kept there during the siege was seen as the symbol of Constantinople’s immortality. Fatih’s troops headed straight there and the symbol, and Constantinople’s Christian primacy, were destroyed..

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

In 692, the reign of Justinian II, the Quinisexte Council was held ‘in trullo’ and this has led to the tiny church of St John in Trullo being associated with that event. Mamboury points out that ‘in trullo’ simply means ‘under a dome’ and postulates that the famous meeting was held in a domed room in one of the great palaces south of the hippodrome. This church seems more in line with the style of the 12th century. It may have been associated with the monastery of which the Church of St Mary Pammakaristos was the centre.

This is a tiny church near Fethiye Camii on Koltukçu Sokak (41.027917,28.945944). It was ruined until a 1966 restoration ‘found the original columns in the basement and replaced them’ as the sign outside says. Freely scoffs at this and at the restoration in general. It’s a pretty little building but perhaps not an authentic example of a Byzantine church.

The church is locked except at prayer time. The interior is so small and convoluted as to be claustrophobic. The floor seems to be higher than in the original design. The ‘found’ columns have some hastily worked capitals in a sort of Justinian Corinthian design. Still, the interior is fascinating, although fitting so many people in for prayers is more an exercise in Tetris than in worship.

Van Millingen makes the interesting observation that this is the only remaining Byzantine church in Constantinople in which the three apses are semicircular on the outside as well as the inside. In any case the inside floor area of what, presumably, are meant to represent the diaconicon and prothesis is too small to have any functional use. The diaconicon was, at some stage, altered to serve as the mihrab. The management realised that it was ludicrously small and at some time in 2016 imported a matching set of blue-and-white tiled mihrab, mimber and lectern. These, although Lilliputian, take up a large percentage of the floor space in the mosque.

Freely, John (1983) Blue Guide: Istanbul. London: Ernest Benn, New York: W.W. Norton

Matthews, Thomas (2001): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Text available online at http://media.library.ku.edu.tr/reserve/resspring09/achm502_ARicci/the_byzantine_churches_of_istanbul.pdf Photographs available at http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/

Micklewright, N (2013) Artamanoff: Picturing Byzantine Istanbul 1930-1947. Koç Üniversitesi Yayınları, Istanbul. Images available online at: http://icfa.doaks.org/collections/artamonoff/items/index/page/4?sort_field=collection_id

If the above link does not work, try this: http://images.doaks.org/artamonoff/items/browse?search=Trullo&submit_search=Search

Müller-Weiner, Wolfgang (1977) Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut) Verlag Ernst Wasmuth Tübingen

Ousterhout, Robert (2000): Contextualizing the Later Churches of Constantinople: Suggested Methodologies and a Few Examples. Dumbarton Oaks Papers No: 54. Washington D.C. Text available at:http://www.doaks.org/resources/publications/dumbarton-oaks-papers/dop54/dp54ch13.pdf

Van Millingen, Alexander (1912): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Available at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is in a tyre storage depot at 32 Draman Caddesi (48.029557,28.943009). In 2014, when I asked at the entrance about the antik kilise, everyone seemed to be familiar with deranged foreigners wanting to see the old rubbish. You can see a little bit of the walls of the crypt cowering behind great towers of steel radials.

Boğdan Sarayı appears to have been part of the Monastery of John the Baptist in Petra. The ‘petra’ may refer to the outcrop of rock that was visible to the west of the building, perhaps the one atop which Kefevi Camii currently perches. It is oriented on a north-south rather than the usual east-west axis. This seems to indicate that it was not a major church. Müller-Weiner agrees with a swathe of experts in saying that this was probably a funerary chapel. Three tombs discovered in 1918 (Mamboury p220) support this view.

There is less of a consensus about the date of construction. The Monastery of Petra existed centuries before the building now called Boğdan Sarayı. Van Millingen (pp280-287) presents a mass of detail from travellers’ reports about the history of the monastery but, unusually, offers no opinion regarding the origin of this particular building. It shares features of late Byzantine building so presumably dates from the restoration of the empire to Constantinople after the Latin adventure petered out in 1261. There is evidence to support construction dates in the 12th (Mamboury) and 14th (Müller-Weiner) centuries. A likely explanation is that a restoration was carried out at the later date. Much of the bricks-and-mortar evidence existing in the early 20th century on which to base such conjecture has now disappeared.

The commonly accepted name of Boğdan Sarayı appears to stem from its status in Ottoman times as a chapel attached to the residence of the representatives of Moldavia, referred to by the Turks as ‘Boğdan’. This was established after Sultan Suleyman conquered the region in the early 16th century and envoys needed an appropriate residence from which to negotiate their erstwhile country’s fate with the Sublime Porte. The catastrophic fire of 1784 destroyed the residence and rendered the chapel unusable. Paspates visited in 1877 and reported seeing ikons, but that they were already being damaged by the locals. Since then it has crumbled away, often with human assistance.

Van Millingen (p280) and Mamboury (p220) present the same photograph showing Boğdan Sarayı with two storeys and its dome, standing alone in wide-open fields. This must have been taken before 1912. According to Freely (p224), the owner of the building in the early 20th century demolished the upper storey in order to sell the building material. It seems likely that some of this material went into this interesting chimney about 20m from the remains of the chapel.

A 1938 photograph by Nicholas Artamonoff shows the northern crypt of the chapel.

This photograph is probably from about 1983, when the Archaeological Museum did some work on the site.

Now all that remains is the northern end of the crypt. It was a substantial crypt, and maybe a little too much above ground to merit the name. It possessed a solid apse with some attractive brickwork which is still visible when not being used to store tyres. Until recently, piles of radials have obscured almost everything. However, a heavy snowfall in January 2017 caused the collapse of the flimsy roofing of the neighbouring sheds and Boğdan Sarayı was cleared. At present, the building is enjoying greater visibility than it has for decades.

The exterior of the apse can be viewed from Cepken Sokak. At the end of this street, at the point at which it intersects Sebze Bostanı Sokak, are the flattened remains of a Byzantine building. A column base is visible, but little structural detail can be discerned. Perhaps this was also part of the Monastery of St John the Baptist in Petra.

The extraordinary Church of the Holy Wisdom, tucked away in the wilds of Surrey, has a collection of Byzantine bits that includes these capitals claimed to be from Boğdan Sarayı.

Freely, John (1983) Blue Guide: Istanbul. London: Ernest Benn, New York: W.W. Norton

Mamboury, Ernest (1925) Constantinople: Tourists’ Guide, 1st edition. Rizzo and Son, Constantinople.

Matthews, Thomas (2001): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Available athttp://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/

Müller-Weiner, Wolfgang (1977) Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut) Verlag Ernst Wasmuth Tübingen

Van Millingen, Alexander (1912): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Available at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is in the vast belt of cemeteries outside the land walls. Walk out of Silivri Kapı, cross the road, take the first right and keep walking. In the middle of the graveyards and men with chisels chipping out names on marble, there is an island of Christianity (41.006808,28.915887). Pilgrims still come here in large enough numbers to supply business for the upmarket Manastir Café and Restaurant.

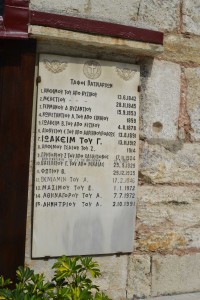

The healing powers of the spring have brought people since pre-Christian times. Justinian appears to have built a church here in the 6th century although there was probably one already there. Destruction by earthquake (8th C), burning by Bulgars (928), and conquering Ottomans (1453 and thereafter) meant that there was little remaining to tempt anyone to confiscate the land from the Greek Church. When the Patriarchate asked for permission to rebuild in 1833, the current building over the ayazma was constructed. There is a walled cemetery for the Orthodox Patriarchs who have died since this church opened. The bekçi is absurdly helpful and will use his collection of enormous iron keys to unlock wherever one asks. Not unreasonably, he will expect a tip.

Hardly a Byzantine church, but the spring is original and so, according to legend, is the lineage of the fish that still inhabit it. Inscriptions on some of the headstones you will probably walk over to get around the grounds are in Karamanlı, Turkish language written in Greek characters.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

There are a few bits of Byzantine wreckage here (41.004893,28.936502). It is in the south-west corner of the Cerrahpaşa hospital complex. The Medrese, a work of the great Sinan, has been reconstructed on the site but a wall with two remaining apses gives us a good impression of what one side of the church was like. According to Mamboury, some good frescoes were still visible in the early 1950s. Now there is a tiny bit of plaster in the central apse.

In May 2014, it was not open to the public. I went in anyway and was shouted at by a man who said he had seen me in there with a CCTV camera. Then followed a discussion in which he became angry. I asked him why he was getting cross. He laughed and said he wasn’t. We shook hands and parted friends.

This seems to be a Palaiologan building with the characteristic bands of alternating dark and light brick as seen in the Fethiye and Kariye mosques. As such it was presumably built in the late 13th or early 14th century. Raymond Janin suggested in 1953 that İsakapı Mescidi was originally the Monastery of Iasites. More recently, Papazotos has provided some evidence that this may be a church from the Monastery of the Patriach Athanasios. This would mean that it was built some time between 1282 and 1289.

In the 1550s, the church underwent its inevitable conversion into a small mosque. Mimar Siman built a tasteful medrese complex around it. This has just been restored by the ever-busy Fatih Belediyesi. The church may originally have had a dome but by the time Paspates carried out his 1877 survey of Byzantine churches in Constantinople, the mescid had a plain tiled roof. Professor Thomas Mathews‘s excellent site has some pictures from 1935 (click on the numbers). Nicholas Artamonoff photographed the site in 1936. The deterioration in the condition of the building is largely due to the effects of the 1894 earthquake, the end of the useful life of the building.

It will take a light touch to preserve this ravaged brickwork as part of a newly contructed building.

Byzantine capitals nestling behind the carpark attendant’s hut at Cerrahpaşa Hospital. These have now been moved elsewhere.

Until now. I was nosing about the area in March 2015 and came across feverish building activity. The architect’s site about the restoration purveys the rather unconvincing notion that the mescid was built by Sinan. Despite this, the work seems to be doing a reasonable job of preserving what remains and supporting it with masonry that reflects the spirit of Palaiologan brickwork. It appears that it may become a library of the history of medicine for the University of Istanbul.

Work was well advanced in June 2015. The old sections of the wall were fully enclosed by modern brickwork and the ticklish task of joining the parts together was nearing completion.

As of January 2016, the building is almost finished. The floors are being done and the men on duty said that it would open as a mosque in (expressive shrugs of shoulders) a few months. A minaret has been built and the Byzantine section of wall is integrated into the whole structure.

I wasn’t permitted to photograph inside but the remnants of fresco seem to have been cleaned with a reasonable degree of sensitivity. This is certainly no longer a Byzantine structure but if nothing had been done, it would have been a pile of stones in twenty years. So thanks, Fatih Belediyesi.

As of July 2019, building work in the surrounding hospital restricted access to the site. It looks as if the mescid and medrese are not yet in full use.

« Previous Entries Next Entries »