This little rectangle is in an IETT bus depot on Millet Caddesi near Topkapı (41.017439,28.928287). It is probably the remains of something much larger but, for now, it serves as the place of worship for the drivers. It has a couple of nice columns with Byzantine capitals.

It’s quiet and peaceful in there, unlike the chaos outside. Sometimes, it’s locked, sometimes it isn’t.

Across Millet Caddesi (41.018702,28.928126), Kürkçübaşı Ahmed Şemseddin Camii (1511) has a porch supported by a row of Byzantine columns that have clearly seen service in an earlier building. Van Millingen suggests that these came from a substantial building belonging to the 13th century monastery of which Manastir Mescidi is the only remaining intact part.

As of November 2016, Kürkçübaşı Ahmed Şemseddin Camii is closed for fairly massive renovation. The porch has disappeared and the columns are currently standing in a row on their own. The rest of the building has been stripped back to bare stone and much of that has been replaced.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is just across the road and up the hill from Odalar Camii and probably belongs to the same monastery, which might have been the Monastery of St John in Petra. It burned down in a fire in the early 20th century. It is a solid-looking rectangular block and probably not a church, but another building from the monastery. I couldn’t get in and was taking a photo over the high wall when an efficient woman came out of an apartment block, led me back to the door and showed me how to pick the lock (41.028757,28.939528).

Immediately to the south of the building is a Byzantine cistern. Freely (1983) was dismissive of Kasım Ağa Mescidi itself, which apparently was a ‘very mean hovel’ in the ruins. However, he commented on the beauty of the cistern (İpek Bodrum) with its Corinthian column capitals. The cistern is now inaccessible (at least, I can’t get in) and the roof is occupied by a playground off Kurtağa Çeşmesi Sokak.

Freely, John (1983) Blue Guide: Istanbul. London: Ernest Benn, New York: W.W. Norton

Mamboury, Ernest (1925) Constantinople: Tourists’ Guide, 1st edition. Rizzo and Son, Constantinople.

Matthews, Thomas (2001): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Available at http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/

Müller-Weiner, Wolfgang (1977) Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut) Verlag Ernst Wasmuth Tübingen

Van Millingen, Alexander (1912): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Available at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

[See below for new details of Odalar Camii]

Not much left of this now. Behind the Cistern of Aetius, the wall between numbers 18 and 20 Müftü Sokak is a ramshackle Byzantine thing with identifiable bits of marble sculpture and some hefty buttresses.

While I was photographing this, the kids in number 20 went to get a woman who let me into the yard at the back. This contains some arches, masonry and holes to fall into, all that remains of a once great monastery. (41.029119,28.939933)

The old church has resurfaced. As of May 2017, the residents have been cleared out and the Byzantine walls are clear of the more recent brickwork.

Work started in about February and the demolitionists have done a reasonable job of leaving the church walls intact. Nobody in the area seems to know the plan for the building. They fear that it will become a rubbish dump, a realistic fear as the building rubble on the site is disappearing beneath daily deliveries of household waste.

According to Muller-Weiner (1977), the church now visible is built on a substructure from an earlier church. The dedication of this church is the subject of an academic battle based on threadbare evidence and into which I am not qualified to contribute. This substructure is said to contain 16 rooms. Some sources suggest that these underground rooms (Turkish odalar) are the source of the common name of the mosque. Another suggested origin of the name is the mosque’s proximity to Janissary barracks, built in the late 18th century.

The last real examination of the basement was done in about 1935 after the dome had fallen in but the superstructure of church was mostly intact. This was wrecked in the fire of 1919, after which the land and walls were fair game for anyone who wanted to put up a quick house.

The existing church is arranged roughly along a west-east axis. There are three naves in this cross-in-square structure. The centre is by far the largest. The wall that was previously the most visible part of the building is the boundary between the centre nave and the narrow northern one. Things are not so clear in the southern section. A small piece of the southern wall of the diaconicon is visible, but is not in line with any existing nave wall. It appears that some reconstructions (probably during the building’s time as a mosque) removed most of the southern nave.

The western wall is the best preserved and still supports some houses on Kasim Odalar Sokak. The wall contains some nice arches and illustrates the recessed brick technique that is the main reason for dating this church to the end of the 12th century. Westphalen (1998), in the most comprehensive published survey of the church, thinks this church may have looked similar to Eski Imaret Camii in its prime.

Details of a narthex are obscured by the houses that are still tucked under the western wall of the naos. There is clearly a great deal to see under the ground in this area.

It appears that the church was not converted to a mosque until some time after the 1453 conquest. The Ottomans conquered Kaffa (a Genoese colony in the Crimea) and immediately moved the potentially rebellious Latins to this area of Constantinople. The area also contains Kefeli Camii. This was named after the immigrants from Kaffa. At this point, Odalar Camii appears to have been called St Mary of Constantinople. The inhabitants do not appear to have settled to the satisfaction of their rulers and in 1636, the Christians were booted out to Galata and the decrepit building was converted to a mosque.

It will be interesting to see what happens to the building now it has been cleared. It is a little close to the existing Kasim Aga Camii to be rebuilt as another mosque but that is a likely fate.

The site has been left since about March 2017 and I will keep an eye on it.

By July 2019, someone had built a dwelling in Odalar Camii.

Maybe the urban renewal has stalled for the time being.

Vitalien, Laurent. Travaux archéologiques à Constantinople en 1935. In: Échos d’Orient, tome 35, n°181, 1936. pp. 97-111;

doi : https://doi.org/10.3406/rebyz.1936.2860

https://www.persee.fr/doc/rebyz_1146-9447_1936_num_35_181_2860

Westphalen, Stephan. Die Odalar Camii in Istanbul. Architektur und Malerei einer mittelbyzantinischen Kirche (Istanbuler Mitteilungen, Beiheft 42), Emst Wasmuth Verlag, Tübingen 1998, XIV + 162 σελ., 40 πίνακες, 4°.

https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/makedonika/article/viewFile/5704/5443.pdf

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

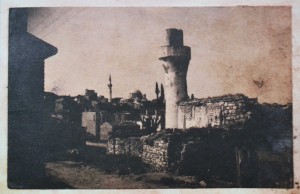

This undistinguished but pleasant building lies in the maze of streets behind the cistern of Aetius, the sunken football ground and park near Edirnekap (41.029364,28.941481). There seems to be some agreement that it is probably the remains of the refectory of the monastery of St John in Petra, because it’s sort of in the right place and because it doesn’t look like a church. It is very close to the Odalar Camii (Monastery of the Blessed Virgin Mary) and they may have been parts of the same establishment.

Anyway, the outside looks nice with those alternating stone and brick layers. The minaret was restored in 1970 and the rest of the building had a wash and brush-up in 1989. The taciturn bekçi will let you in, prohibit photography and expect a tip. The ban on photos is not a bad thing because the internal decoration of the mosque is fairly horrible.

As of early 2017, the interior of Kefeli Camii has been redecorated and looks rather pleasant again.

References

Freely, John (1983) Blue Guide: Istanbul. London: Ernest Benn, New York: W.W. Norton

Mamboury, Ernest (1925) Constantinople: Tourists’ Guide, 1st edition. Rizzo and Son, Constantinople.

Matthews, Thomas (2001): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Available athttp://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/

Müller-Weiner, Wolfgang (1977) Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut) Verlag Ernst Wasmuth Tübingen

Van Millingen, Alexander (1912): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Available at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is a picturesque church with a strange, rambling shape because of the many additions and modifications it has endured. It has a multiplicity of domes of different sizes, which gives it something of a fairytale appearance.

Unlike most of the other major churches in the district, it is hard to find by simply bumbling around. It is at the end of Fethiye Kapısı Sokak, a turn-off from Fethiye Caddesi downhill from the Selimiye. (41.02881,28.946164). The larger part of the existing building is once more in use as a rather austere mosque. It is always open, unlike the museum part which is closed on Wednesdays. The museum is the parekklesion, or side chapel, that houses the mosaics, far less extensive than in Kariye but just as lovely.

Mamboury suggests that the church was built in the 8th century but adds that the original church is hard to recognise. So much so that most archaeologists date its foundation to the 11th or 12th century. This refers to the older church that is now a mosque. The parekklesion was added to the south of the church in the 13th century as a memorial chapel to one of Andronikus II’s generals. The richness of the shrine gives some idea of how lucrative being a general must have been.

This church was the Patriarchate for a while. The great Patriarch Gennadius, who was apparently consulted on matters of theology by the conquering Sultan Mehmet, moved his HQ here in 1456 from the decrepit Church of the Holy Apostles, the site of which was required by Fatih for his fabulous new mosque. In about 1586, Sultan Murat III decided that this church too was to become a mosque so the patriarchate moved down the hill to the Church of Theotokos Paramythia (Vlach Saray). The conversion to a mosque resulted in the walls between separate buildings and chambers being knocked down and a sort of triangular bit being built on to enable a mihrab to face Mecca. This made a much more open structure but created a puzzle for the Byzantine Institute in their preparation for the restoration in 1949.

The mosaics were considered by Mamboury to be superior to those in Kariye. There are traces of frescoes remaining but these have largely been destroyed in the various remodellings that the building has endured.

Only one mosaic remains from what appears to have been a life-of-Christ series similar to the example in Kariye. This displays the baptism of Christ in a slightly surprising full-frontal format.

In the arches and small domes on the south side of the church are portrait mosaics of saints, including a fine one of Gregory the Illuminator, driving force behind the Armenian church.

In the semi-dome of the apse is a lovely mosaic of Christ Hyperagathos, said by Freely to mean ‘all-loving’ but more commonly interpreted, as in the Dumbarton Oaks literature on the church, as ‘supremely good’. This appears to be an attempt to depict the concept of John Scotius Eriugena’s 9th century concept of ‘more than goodness‘. This masterpiece is flanked by full-length representations of John the Baptist and Mary, the Theotokos Pammakaristos to whom the main church was dedicated.

In the dome is the traditional Christ Pantocrator (the all-powerful), in this example surrounded by twelve prophets of the Old Testament – Moses, Jeremiah, Zephaniah, Micah, Joel, Zechariah, Obadiah, Habbakuk, Jonah, Malachi, Ezekiel and Isaiah. Some interesting choices in that list.

The mosaics that remain are marvellous in their own right but give a tantalising glimpse of what must have been a magnificent work of art in its totality.

There is a long inscription of a dedicatory poem by Manuel Philes, both on both the inside and outside of the church. Van Millingen provides a translation of this in his definitive 1912 work on Byzantine churches. He also provides some pictures of the church before the Dumbarton Oaks restoration.

« Previous Entries Next Entries »