Excavations in Saraçhane for the Şehzadebaşı intersection in 1960 revealed the remains of a massive Byzantine church (41.014062,28.952971). Bigger than the Sülemaniye Camii, it was a basilica dedicated to St Polyeuktos. It has fallen a long way since its heyday in the sixth century. These days, it is the sort of public toilet in which George Michael may feel rather out of his depth. The razor wire and the locking up at night do not prevent the diurnal sleaze and defaecatory activity. When I was there, a man faced deep into a niche for at least twenty minutes, clutching an intimate portion of his anatomy. Don’t take the children.

There is one thing that can be said for the 1204 sack of Constantinople by the barbarians of the fourth crusade – it preserved some lovely pieces from the Church of St Polyeuktos. These can be seen in the vicinity of the Basilica San Marco in Venice. The pillars of Acre don’t come from Acre, they come from this church. The vandals who stole the porphyry sculpture referred to as The Tetrarch left a foot behind. This was dug up in 1960 and matched the missing limb from the statue in Venice.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This church has been brought to renewed prominence by the opening of the Vezneciler Metro Station in 2014. As one surfaces on the escalator, one is faced with a perfect Byzantine church (41.013187,28.960133). The interior is lined with attractive marble and gives rise to a pleasant monochrome, appropriate for reverential activity should one be in the mood.

Although the Kalenderhane itself has been restored, it is surrounded by ruins which have presented a puzzle for archaeologists. For now, we generally use the interpretation of Matthews. This website has some excellent photos, all of which are labeled ‘Isa Kapisi Mescidi’ a name that refers to a building which lies some kilometres to the west.

The first church on the site was built in the sixth century. Its apse survives, owing to its protected location hard against the Aqueduct of Valens.

The arch at the bottom leads into the apse of the 6th century church. At left is the aqueduct, at right is the late 12th century church

The current church appears to be largely from the late 12th century although its foundations seem to be from a church of similar dimensions built in or around the 800s.

Massive brick pier from the north side of the church, possibly part of the dome support of the 6th century church

The apse of the first church is currently (summer 2017) seeing service as a dormitory for otherwise homeless men.

From the apse, one finds the entrance to the prosthesis. The two chapels either side of the central apse in the main church have been bricked up and are not accessible in the usual way. Pictures from 1914 show them to have been accessible from the naos, as one would expect.

There is something of a jumble of stonework in parts of the eastern end of the complex, where building styles of three eras intersect.

On the eastern end of the south exterior wall of the church is the entrance to a chapel. Investigations in the 1960s revealed some lovely frescoes of the life of St Francis of Assisi. These were added during the Latin occupation (1204 – 1261) in about 1250. The frescoes, together with the only surviving pre-iconoclastic mosaic in the church, are now in the Archaeological Museum.

The minaret is very recent, being rebuilt during Kuban ad Striker’s restoration. Liddell reports seeing the muezzin calling the ezan from a high stone in the 1950s. The picture below from 1951 shows how much the building has changed since then. I struggled to recognise it as Kalenderhane until I looked at van Millingen’s illustrations.

Striker and Kuban carried out the definitive study of the church and its surroundings in the 15 years from the time Striker gained permission to break the lock of the derelict hulk in 1966. They have traced the identity of the main Kalenderhane church as part of a monastery dedicated to the Mother of God who Reigns in Majesty (Theotokos Kyriotissa) on the basis of inscriptions found in the church. A review and summary by Robert Ousterhoult of the first volume of their published study may be found here. The great Dogan Kuban still takes breakfast occasionally on the terrace of the Adahan Hotel.

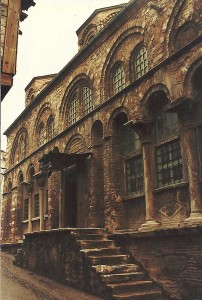

The main church is constructed of alternating courses of stone and brick. It forms a Greek cross with semi-circular section barrel vaulting over the four arms. The scalloped edge of the 16-rib dome was restored in the 1970s and looks very different from the 1950s incarnation of the church.

The really distinctive feature of this church is the marble revetment. This includes some elaborately carved marble icon frames either side of where the iconostasis was placed.

Icon frame on the north side of the church. The arched (former) entrance to the prothesis can be seen at lower left

The St Francis chapel is in the area of the diaconicon on the south-east corner of the church.

Flanking the present-day south and north walls of the church are parallel walls that are partially destroyed. According to Matthews, these marked the extent of aisles either side of the main nave that were destroyed in Ottoman times.

Matthews, Thomas (2001): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Available at http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/ Retrieved 16 Oct 2017

Müller-Weiner, Wolfgang (1977) Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut) Verlag Ernst Wasmuth Tübingen

Ousterhout, Robert (2000): Contextualizing the Later Churches of Constantinople: Suggested Methodologies and a Few Examples. Dumbarton Oaks Papers No: 54. Washington D.C. Text available at:http://www.doaks.org/resources/publications/dumbarton-oaks-papers/dop54/dp54ch13.pdf Retrieved 16 Oct 2017

Van Millingen, Alexander (1912): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Available at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm Retrieved 16 Oct 2017

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

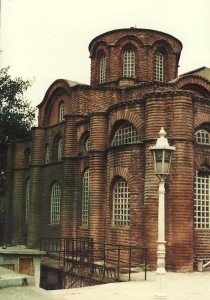

This was burnt down just as van Millingen was publishing his magisterial survey of Constantinople’s Byzantine churches and he included a couple of sad commemorative pictures of the ruin. It was in a sad state and serving as a rubbish dump when Mamboury was writing in 1951. Freely reported that it was a ‘mere shell’ in the late 1970s. It was a surprise, then, to be presented with this neat little gem when I headed downhill from Laleli Camii on a winter day at the end of 1990 (41.008597,28.955632). It is perhaps a little too neat to be true to its original appearance but it stands there looking like the archetypal Byzantine church and I rather like it. It does look a bit like a sculpture made out of stacks of coins, though.

Perhaps the real interest in this area comes with the bodrum (basement) rather than the cami. The church itself was built on a massive basement with one of the tallest crypts that has ever existed.

To the south-west of the church is an improbably large, circular open space paved with marble.

If you enter the Mirelion Çarşısı beneath this terrace, you will find a thriving Balkan fur trade conducted in a forest of Byzantine columns.

It appears to have had its genesis in someone’s desire to build a Pantheon-like rotunda here in the 5th century. The dome was never finished and in the early 10th century, the emperor decided to put the columns in and use the resulting structure as a foundation for a palace. The church attached to the palace was what we now see as Bodrum Camii. The rotunda was later used as a cistern, then sat about in a derelict state for a few centuries until someone thought of selling furs (and luggage) there.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is in an area on the western slope of the hill below Süleymaniye that is earmarked for urban renewal (41.016296,28.960165). As of 2014, most of the surrounding houses are in ruins and used by the eskici as temporary warehouses and sorting yards. The church itself is dirty and unkempt. I like it that way. It means that it has not yet undergone one of the municipal homogenisations that have befallen so many of the other historic buildings in the district. It has the world’s grumpiest bekçi who has an extensive vegetable garden at the back.

It’s an odd building with a wide, arch-and-column porch on the entrance side (14th century) and a very traditional looking four-column church (variously dated as 8th to 12th century). The great joy of this church is the treasure hunt through its building materials for recycled sculpture from as far back as the 5th century.

Oddly, the brick minaret adds to the building. It is a handsome fluted design and fits in with the spirit of the rest of the place by reusing older Byzantine bits that were lying around.

The theme of recycling is evident in the outer narthex where some 5th century columns are still doing sterling service. The south dome has some barely disguised frescoes of a similar design to those in the dome of the parekklesion of Kariye Camii. The central dome has the kind of texture that suggests that significant mosaics have crumbled away. The inner narthex is swathed in virginal white plaster. There has been some laser measurement going on in early 2015 so a restoration might be in the offing. Maybe someone will uncover some decoration.

The nave is a pristine white mosque interior. It is probably not a good idea to congratulate the imam on the beauty of his church. I did. He used dignity and humour to make me feel silly.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

For the post-restoration church, click here.

This is on the main artery of Vatan Caddesi, shrouded with scaffolding in 2014 and enduring one of Fatih Belediyesi’s uncompromising restorations. It’s an awkward-looking building, an agglomeration of different churches and bits built on. The two bulging domes give it the aspect of a cartoon frog. Some of the foundations date from the 6th century and the two main churches come from the 10th and the late 11th centuries. The charm is in the details. There was some nice sculpture here. The brick swastika decoration on the eastern façade was pretty. There are some chapels on the roof. Let’s see what the restoration does with it. (41.014863,28.943878)

September 2017: The temporary mescit has been demolished and the restored mosque looks ready to enter service.

As of July 2019, the restoration is complete and the mosque is open for use.

« Previous Entries Next Entries »