This takes persistence to find. The location is a piece of open land, clearly with a preservation order because any gecekondu building activity has been swiftly demolished. Hence it serves as a rubbish dump for the surrounding houses and businesses (41027507,28.95476).

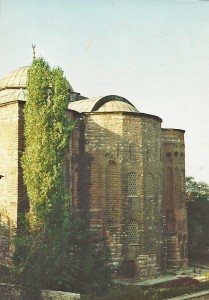

In the furthest recesses of this wasteland is a jungle of fig trees and Virginia Creeper. Beneath this is a section of intricately patterned, unmistakeably Byzantine, brickwork. It is the curved eastern wall of the apse of a church that, after the conquest, became Sinan Paşa Mescidi.

Paspates reported in the 1870s that there was a good deal of the church remaining. Now it is difficult to see that there was a building there at all. If you must go and see it, do so in winter when the rubbish smells less and there are fewer leaves obscuring the remains.

This vault was open as of August 2015

In July 2019, the site is securely fenced off and in use for eskici storage and rubbish dumping.

The new excavations that reveal the eastern elevation of the vaults appear to have little to do with archaeology. However, the arches are no longer used for storage. I’ll keep an irregular eye on it.

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

As you walk along Ayakapı Sokak, a blank wall comes into view (41.027883,28.95627). As with many in Istanbul, it bears the marks of alterations and the traces of the many buildings that have been attached to it. At the bottom of the wall, a characteristic Byzantine arch looks tiny because of the inexorable rise of the surrounding ground in the long time that it has stood here. This is what remains of the Ayakapı Chapel.

The wall is now part of a building in which a welding shop operates. The inside provides something of a surprise with a lot more Byzantine stonework than the outside hints at. The welder is knowledgeable about the history of his workshop. In 2014, he was visited by archaeologists from Istanbul University. According to them, Ayakapı Chapel was part of a monastery. The south-east wall of the chapel contained 15 window arches stretching all the way to the defensive wall beside the coast road.

In July 2019, the area is being gentrified. There is a street cafe in Ayakapı Caddesi on the south-east side of the chapel.

The patch of land with the external wall is up for sale and I don’t know what implications this has for the future of the chapel.

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Imperial sarcophagi from the Church of the Holy Apostles, now in the atrium of Aya Irini

This giant Byzantine structure served as the Patriarchate after the Conquest, when Aya Sofya was immediately taken over as the primary mosque of the newly Muslim city. It lasted the short time that Fatih Sultan Mehmet needed to realise that the Church of the Holy Apostles was on the most impressive location in his new possession (1453 – 1456). It was already in a sad state of repair. The first incarnation of Fatih Camii was completed between 1463 and 1470 and the Holy Apostles were no more. The many rebuilds and additions, modifications and subtractions of accessory buildings have meant that anything of the Byzantine church disappeared centuries ago. An ongoing restoration of the entire complex will complete the obliteration of anything that does not remind one of the glory after 1453. (41.019311,28.950369)

The Church of the Holy Apostles was already in a lamentable state immediately prior to the Latin invasion of the fourth crusade in 1204. Emperor Alexios III Angelos, not the most reliable or stable of characters, had spent the contents of the treasury and was faced in 1196 with a demand for protection money from Henry VI of the Holy Roman Empire. Alexios had to plunder the tombs of the emperors, including Constantine the Great and Justinian, in order to raise the funds to avoid an earlier invasion. Some of the solid porphyry sarcophagi are now at the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul. They show clear signs of their desecration in 1196. All this meant was that the Latins found a little bit less to steal eight years later.

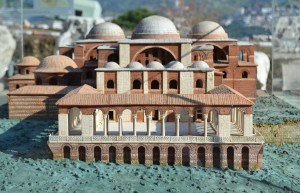

In place of the Church of the Holy Apostles, it is appropriate to display a picture of the türbe of Fatih Sultan Mehmet. This stands on the site of the church. Although the church disappeared in the 15th century, it leaves an architectural legacy in the form of a number of churches that have followed its basic cruciform structure of a dome over the centre and four more, one over each arm of the cross. These include the Basilica of St John in Selçuk (once part of Ephesus) and Basilica de San Marco in Venice. The latter undoubtedly has bits of the original Church of the Holy Apostles somewhere in its lucky-dip structure.

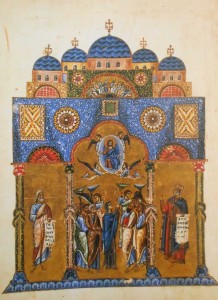

An image from 1162, which matches the description of the Church of the Holy Apostles and hence probably is. Library of the Vatican.

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This fortress of a church is visible for miles around but it tends to be a bit tricky to find in the labyrinth of streets around the new Kadir Has University 41.026912,28.956147). The church looks as if it has been built on stilts. The massive crypt would be a tremendous location for filming a horror movie.

The inner door is locked when not in use so go in at prayer time. Nobody seems to mind if you’re respectful. The restoration of the nearby hamam complex will make this a picturesque neighbourhood.

This is a cross-in-square church from the late 11th/early 12th century with a lot of Ottoman repair and restoration. As usual, the original dedication is lost but reasonable guesses lead to its identification with the Church of St Theodosia. Theodosia was an iconodule heroine who attained her fame at the start of iconclast rule by shaking a ladder that a soldier was using to remove an image of Christ from the Chalke Gate. He died. Theodosia was executed and, with the defeat of iconoclasm became a saint and a retrospective virgin. The present Gül Camii may be the church in which her relics were kept.

There are several other candidates for the dedication of the church but the travelling German scholar-priest Stephan Gerlach decided in the 16th century that this was the Church of St Theodosia. The origin of the current name of Gül Camii (Rose Mosque) stems from the story that at the time of the Ottoman Conquest in 1453, the church was decorated with flowers for the feast of St Theodosia. The Emperor and Patriarch had just conducted the last mass and high-ranking ladies had gathered to pray for a different outcome to the day’s events. When the Sultan’s soldiers entered the church, they were greeted with the sight of roses. It was not until 1490 that the building was renovated and reopened as a mosque but story is that it was named Gül Camii because of those flowers. On the other hand, it seems that an Ottoman holy man named Gül Baba is buried in the building. This may be the slightly less romantic origin of the name.

The two outer apses on the south-eastern face are probably original. They look very much like similar features on the south church of Zeyrek Camii (now plastered over), built at about the same time. The central apse looks very different and probably stems from a restoration in the early 17th century following an earthquake. The dome is probably from this time, replacing a higher one that had been mounted on a drum.

In late January, 2015, there was some laser positioning work going on in preparation for a putative restoration. The painting in the interior comes from the 18th century and shows significant damage from damp. In January 2016, the place looked in need of some attention to stop the plaster from falling on the heads of the worshippers.

Foundation of the Hellenic World. (2008) Theodosia (Gül Camii) Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World. Available online at: http://constantinople.ehw.gr/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=11775#noteendNote_2 Accessed 14th April 2016

Müller-Wiener, W., Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls, Byzantion – Konstantinupolis – Istanbul (Tübingen 1977), pp. 141-143.

van Millingen, A. (1912) Byzantine Churches in Constantinople: Their History and Architecture. Macmillan, London. pp164 - 182

Available online at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm

Accessed 14th April 2016

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

In the 1990s, I often used to walk past this little brick octagon without realising that it was a Byzantine building. It is on the road down from At Pazarı in Fatih to the Zeyrek Camii (41.019089,28.955256). As of 2014, it is encased in a white shroud as Fatih Belediyesi does whatever it is going to do with it. It forms the wall of a neat little house attached to its northern side. Freely advances the idea that Şeyh Süleyman Mescidi was once a library or chapel of the monastery of the Pantokrator.

Active work had begun on restoration in August 2015.

It will be interesting to see the use to which Fatih Beledeyisi puts this lovely little building. The restoration appears to be nearing completion. I am hoping that it becomes a library. If so, it will be an Islamic one like the lovely Recai Mehmet Efendi Kütüphanesi in Vefa.

The roof is complete. August 2015

No such luck. The plan is for Şeyh Süleyman Mescidi to reopen as a mosque in mid-2016. The roof is finished and the shrouds are coming off. In January 2016, the caretaker said that the major building work was due to be completed by February/March. Interestingly, he is Syrian and has a better command of English than Turkish. An army of Belediye labourers is building a wall and a new road surface around the structure.

Şeyh Süleyman Mescidi opened as a mosque in February 2017.

Basın İlan Kurumu (2017) Restore edilen Şeyh Süleyman Mescidi açıldı. Available online at: http://www.bik.gov.tr/restore-edilen-seyh-suleyman-mescidi-acildi/ Accessed 25th Feb 2017

« Previous Entries Next Entries »