The current, very handsome, church was built in 1841. There has been a convent dedicated to St Peter here at least from the late 15th century and it may have been established before the 1453 conquest. Once Mehmet II appropriated the large Church of St Paul (or Domenico), the Dominicans Moved uphill and, after some overcrowding, a larger church and monastery were built in 1603-04.

The church is set into one of the remaining fragments of the Genoese walls of Galata. Among the many sacred possessions of the church is a venerable icon of the Virgin Mary of Hodegetria. The church is open every weekday morning between 7 and 8. (41.024779,28.973029)

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

If you turn right as you come out of the bottom station of the Tünel, cross the road and take the first street towards the shore, you will see a messy passageway on your right. Through the archway lies the fabulously unkempt Rüstem Paşa Hanı (or Kurşunlu Han), a lovely early Ottoman collection of workplaces.

On the left as you pass through the archway is an upturned Corinthian capital with a water pump attached to it. It has probably been there since the han was built in the mid 16th century. According to Freely, the capital probably came from the Latin church of St Michael, which previously stood on the site. (41.022472,28.972519)

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is now within the high walls of the Avusturya Lisesi, the Austrian High School, but it is open for worship on Sundays at 10am. According to Mamboury, a church was built over the sacred spring of St Irene at a time that seems to have made this the earliest church in Byzantium. The current church dates from 1731. (41.024188,28.973383)

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is something of a sanctuary among the maze of workshops and unwise attempts to get vans into places that they won’t go (41.024423,28.971183). There is a lovely courtyard with a şadırvan and seats in the shade. The bekçi is probably the most conscientious in Istanbul. It’s worth going in on a sunny spring morning when he has opened all of the windows and the place smells fresh and airy.

There are a few remains of a 6th century Byzantine chapel, probably dedicated to St Irene, including a column base that was revealed by excavations.This is possibly the one referred to by Procopius in his Buildings (page 65-67). If so, there might be a lot more to be excavated than has so far been hinted at.

A Latin Chapel to St Paul was built on the site in 1233, during the Latin occupation of Constantinople.

In 1307, the Byzantines were back in charge and Emperor Andronikus II Paleologos relegated the Dominican friars to the Galata district. There was already a Dominican monastery in the area. The current building, dating from 1325, is a long, rectangular Latin church in a rather pleasing Gothic style. It was dedicated to San Domenico, although even now people refer to it as the Church of St Paul. It is the only representative of this architectural movement in the city. It has a nice, tall belfry which has not been diminished by conversion into a minaret. It was restored in the early 20th century when the wooden galleries were added.

Mehmet II decided soon after the conquest that it would make a fine mosque, which it does. The Dominicans were shifted up the hill to the Priory of San Pietro which thereafter was dedicated to Peter and Paul. Towards the end of the 15th Century there was an influx of Muslims fleeing from the Inquisition in Spain. Beyazit II allocated this mosque for their use. The reference by teh locals to the new arrivals as Arabs is probably the origin of the name ‘Arap Camii’.

A persistent legend suggests that this was the first mosque in Istanbul, built during the Arab siege of 715. There is a shortage of evidence to support this, despite the apparently authoritative notices outside. It would appear to be part of the mythology conjured up in early Republican times to promulgate a new Turkish history that would lend itself to an inward-looking, protective nationalism.

Posted June 28, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Robert Ousterhout (2008) refers to a wall ‘recently unearthed’ in Unkapanı that has features similar to the Church of Panagia Krina in Chios.

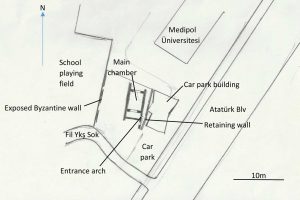

I assume that this is the structure behind the car park of Medipol University Hospital in Atatürk Caddesi (41.02093,28.95906). A retaining wall runs behind the main hospital. The southern end of this wall is broken down and reveals some distinctive arches which point to this being a Byzantine building from the late 12th century. The brickwork is similar to what was left of the Toklu Dede Mescidi, which finally disappeared in the late 20th century. The retaining wall itself appears to be Byzantine, which adds another odd piece to the puzzle.

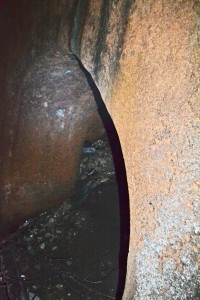

The building remains to be excavated. I assume that someone has done a preliminary study but I have yet to find anything on this building in the literature. There is one small entrance in the larger of the exposed archways. It is at ground level in the exterior wall but 3 metres above the interior floor.

For such a grand window adornment, the entry chamber is tiny, around 5m x 3.5m. It has a brick-domed ceiling and the walls are plastered up to the level of the base of the dome. It is currently filled with branches, as if a hurried gardener needed to find somewhere to hide some prunings. The interesting thing about this chamber is that it has been dug out to floor level, or close to it.

This view from the north shows the retaining wall on the left and the exposed Byzantine church wall on the right.

From this room, a broad archway to the north leads to a much larger chamber, about 9m x 5m. This room is piled high with earth containing a most entertaining assortment of pottery fragments and bones. I remember digging through the rubble and finding, in order, all of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae of a cow. This indicates that, however the contents of the chamber got there, they have not been disturbed for a long time.

The pottery is a mixed bag – tiles, amphorae, plates, pots – some painted and glazed, others natural earthenware. This looks like a place that was used as a rubbish dump for an extended period of history.

One notable piece from this midden is a fragment of painted glass, about 50mm x 30mm. Given the proximity of this building to the Monastery of the Pantocrator, the apparently similar age of the structure and the discovery in the Pantocrator of what appears to be among the world’s first stained glass, this shard may be of significance. It is difficult to say of what this fragment was once part but it bears some resemblance to early glass currently in the Museum of Archaeology.

The main chamber also has a brick-domed ceiling and what appears to be a vertical strengthening rib protruding from the western wall. An arch in the northern side is identical to the one through which one enters this chamber. The room to which this northern arch leads is apparently completely full of debris. Some of the exterior of the eastern wall of this chamber has been exposed and can be seen as one scrambles up the outside pathway to the top of the structure.

The arch to the south of the entry window indicates that there was more of this building in that direction. This remains to be excavated. An abandoned concrete building from the 20th century covers much of the south part of the site. Construction of this may have destroyed the southern part of the Byzantine building.

There is undoubtedly more Byzantine stonework to the west of what is currently accessible. The level of hard-packed debris is uniformly high enough to hide any entrances that may once have led to the western parts of the complex. The prime real estate to the west of Ousterhout’s ‘exposed wall’ is fenced off fairly securely and the homeless population is regularly chased out. There is something exciting under there and I presume that it will be investigated systematically at some stage.

As for what it is, that remains to be seen. The stone and brick, so similar to Panagia Krina, Toklu Dede Mescidi and the south church of the Pantocrator, indicates that his may be a church, or at least a 12th century monastery building. The exposed wall is aligned along the same almost north-south axis the western and eastern walls of the churches of the Pantocrator. However, the accessible chambers have none of the internal features of church architecture. They give the superficial appearance of a narthex.

Perhaps the exposed wall is not from the exterior of the building. Unlike the Panagia Krina, the decorative brick arches could have come from the inside. Mathews’ interpretation of Toklu Dede Mescidi shows the arched section as an internal wall. Perhaps the main body of this church was demolished, leaving the inner narthex. The outside of the eastern wall of the narthex would be the decorative western wall of the nave. There may be an exonarthex on the unexcavated western side. To add to the complexity of the site, there is another arch to the south of the entrance that leads to a chamber blocked off from the accessible chambers. Excavation will reveal a lot.

Mathews, T. (2001) The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Available online at: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/ # Accessed 8th Jul 2016

Ousterhout, R. (2008) Master Builders of Byzantium. University of Pennsylvania Press. Available online at: http://www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/14545.html Accessed 8th Jul 2016

Ousterhout, R. (1995) Beyond Hagia Sophia: Originality in Byzantine Architecture. in A. Littlewood. (ed) Originality in Byzantine Literature, Art and Music. Oxbow Monographs. Available online at: http://eclass.uth.gr/eclass/modules/document/file.php/SEAD343/%CE%A4%CF%81%CE%AF%CF%84%CE%B7%2010%20%CE%9C%CE%B1%CF%81%CF%84%CE%AF%CE%BF%CF%85/Ousterhout-OriginalityByzArchitecture.pdf Accessed 8th Jul 2016

« Previous Entries Next Entries »