There is general agreement that this building began as a Byzantine church. After that, the debate diverges. Mamboury insists that it was dedicated to St Andrew in about 767 and goes on to provide a detailed biography of the place through the ages. Freely thinks it might be from the 13th century but used recognisable bits from the 6th century. It hardly looks Byzantine at all after the restorations and additions since then.

It’s a nice place to be (41.003545,28.928504). It has become a real community centre, with frequent events that are attended well by the community. These include church fete-type fundraisers where you can buy old books and a nice lunch. There is an ancient tree sticking out of a türbe where women go to pray for the acquisition of husband material. Legend has it that the chain still hanging from the dead wood would once indicate which out of two disputants which was telling the truth. Page 107 of van Millingen has the tale of how the chain lost its judicial reputation.

The many additions and reconstructions during the Ottoman period mean that the building has never needed major reconstruction in modern times. This, in turn, means that there has never been the opportunity to expose the fabric of the church for comprehensive study.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is a rather nice little church in suburban streets quiet enough for children to play safely. The people in the car park are friendly and like people coming in to take photos of the outside of the camii. The western side is a steep, ivy-covered wall that forms the limit of the gardens of the houses there. I have been there three times and seen nobody inside. However, it has always been open. It is helpfully placed near Sancaktar Tekke Sokak.

There is a legend that it was established in the fourth century but what we see now seems like a much later building. Alexander van Millingen said it was a 14th century chapel. I’ll bow to him. Freely reported in 1977 that it was a precarious ruin populated by death-defying squatters. Now it’s a pleasant little mosque. (41.002875,28.934523)

As of July 2019, the mescid is as solid as ever but no longer visible from the carpark to the east.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This is no longer anything in particular except a refuge for squatters with an eye for 17th century architecture (41.033284, 28.947541). It was where the envoy from St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai from 1686 until 1967. At this point, it was abandoned and became the only example of a Feneriot mansion that could readily be seen by visitors. There is a nice picture of it from 1982 here. I imagine that it will be restored as a trendy gallery or café at any moment. There is a nice summer café in the grounds on the Golden Horn side which, last time I was there was doing a bad job of keeping the Syrian refugees out.

There is still an intact 19th century basilica attached, the Church of St John the Baptist, built in 1833 but presumably built on the site of something much older.

This may be the finest remaining example of one of the classic Feneriot houses. These were the residences of Greeks and other foreigners who made fortunes from acting as intermediaries between late Ottoman dignitaries the merchants whose languages they would not lower themselves to use. These are some pictures from the early twentieth century of one of these houses (from Diez and Gluck, 1920)

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

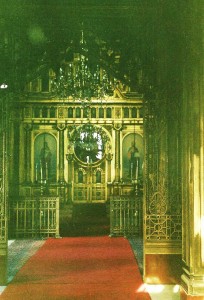

On the lovely Vodina Caddesi is a gateway in a stone wall (41.030877, 28.949342). This is where the friendly bekçi, Abdullah, may allow you entry to the grounds of the Metochion of Jerusalem, a sort of consulate in Constantinople of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem. The walls of the narthex are a rogues’ gallery of the great and good in the Orthodox world. The emphasis in the modern church is more towards bridging than schism and interdenominational diplomatic visits of dignitaries are the rule.

Remnant of Feneriot mansion on the grounds of the Metochion. This was presumably the residence of the envoy from the Holy Sepulchre.

The land enclosed by the walls is a piece of the rural Aegean in the crush of Fener. The Church of St George is a typical 19th century basilica but the grounds preserve scattered bits of the Vlach Saray, the palace of the powerful Cantacuzene family in the last centuries of the Byzantine empire. Now it is the home of a herd of goats, the world’s most slothful guard dogs and some splendid fruit trees, one large fig in particular. A row of huge jars awaits offerings of olive oil from the faithful. There is also a plane tree said to date from the 16th Century. As I write this, I am drinking tea made from chamomile picked by Abdullah.

Posted June 27, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This odd building is representative of the Balkanisation of the Orthodox church that has taken place over the centuries. The Bulgarian minority used to use the Greek Patriarchate as their base in Istanbul. However, the movement for Bulgarian rights within the Ottoman Empire began to gain power through the 19th century. The Ottomans classified minorities by religion, which meant that Bulgarians came under the administration of the Greek Patriarchate. This meant that Bulgarians could not establish schools or celebrate mass in their own language. By the 1860s, nationalist movements in the northern part of Bulgaria had replaced Greek church leaders with Bulgarian in defiance of the rulings if the Patriarchate. A wooden house in the location of the current Church of St Stephen (41.031671,28.949575) was donated and converted into a Bulgarian church in 1849. This was unignorably close to the Greek Patriarchate.

Angry religious nationalism was a threat to stability in the tottering Ottoman Empire so something had to be done. The 1870 firman (royal decree) of Sultan Abdulaziz granted the Bulgarians the right to establish their own church (an exarchate, because it was not recognised by the Greek Patriarchate). The firman was read out amidst great celebration in the church. The Patriarchate officially closed the church. The rebels then held a service in Bulgarian and proclaimed autocephaly, meaning that the Bulgarian Church was no longer answerable to the Greek church. Things went badly at the 1872 Ecumenical Council in Constantinople in which the Bulgarians were excommunicated, their nationalistic demands condemned as heresy and the exarchate branded as schismatic. Exarch Antim I was exiled by the Ottoman government in 1877 for sympathy with the Russians in the recently declared Russo-Turkish war. The Bulgar movement didn’t go away and, inevitably, the wooden church burned down.

A new church was needed, the Bulgarian community had some powerful and rich backers and the designated ground for the church was on swampy, reclaimed ground. A plan for a light, prefabricated church with an iron frame was drawn up. The part were manufactured in Vienna, shipped down the Danube, down the Black Sea and began to arrive on the shore of the Golden Horn in 1896. The Bulgarian church remained a rather obvious entity and the Greek Patriarchate officially recognised it as an Orthodox church in 1953.

The iron church is a surprisingly attractive combination of bits of Gothic and Baroque casting. Once you know it is a prefab construction, you can see the joins but if you forget about that, it’s rather lovely. It is being restored at huge expense. As the first step, the dome was plated with gold in 2010, funded by money raised by the orthodox community of Plovdiv. More details here.

« Previous Entries Next Entries »