This was in Ҫankırı, in central northern Turkey. I was taking pictures of things in my usual way. This was the week before the March 2014 elections when rival factions were squaring off and accusations of treason and terrorism were everywhere. I took a nondescript photo into a valley. A man working nearby told me that there was a Jandarma post across the road and that taking photos was unwise. He was right. I took the hint, thanked him and went away.

Half an hour later, I was driving along a dual carriageway towards Istanbul when I saw flashing lights ahead. I slowed. There were two police cars. The police seemed to be waving more urgently than usual. I noticed that two of them had big, ugly automatic weapons. I parked at the side of the road and took my seat belt off. As I wound down the window, I heard shouting. Keep your hands on the steering wheel where we can see them. I looked up. Two machine guns and a handgun were pointing at me. I put my hands on the wheel and started to worry. Two more policemen appeared on the other side of the car.

One man stood in front of the car with gun disturbingly ready. In the mirror, I could see another behind me. The one with the handgun seemed to be in charge. He told me that I had been seen taking photos of a Jandarma post. This is something akin to a terrorist act in Turkey. I was about to answer when there was a disturbance. Another police car had arrived. The officers who had been there already broke off the interrogation to remonstrate with the latecomers. Apparently they had arrived too late for the roadblock and failed to take an active part in apprehending me.

I sighed and took my hands off the wheel. There was more shouting and I saw those holes in the ends of the guns again. I put my hands back.

The interrogation continued. I put forward the frankly absurd case that my wife worked in Istanbul and I had no job at present and was driving around Turkey taking pictures of things. At this point, they told me to get out of the car and open the boot. All it contained was a baby buggy. “You have a child?” I admitted this.

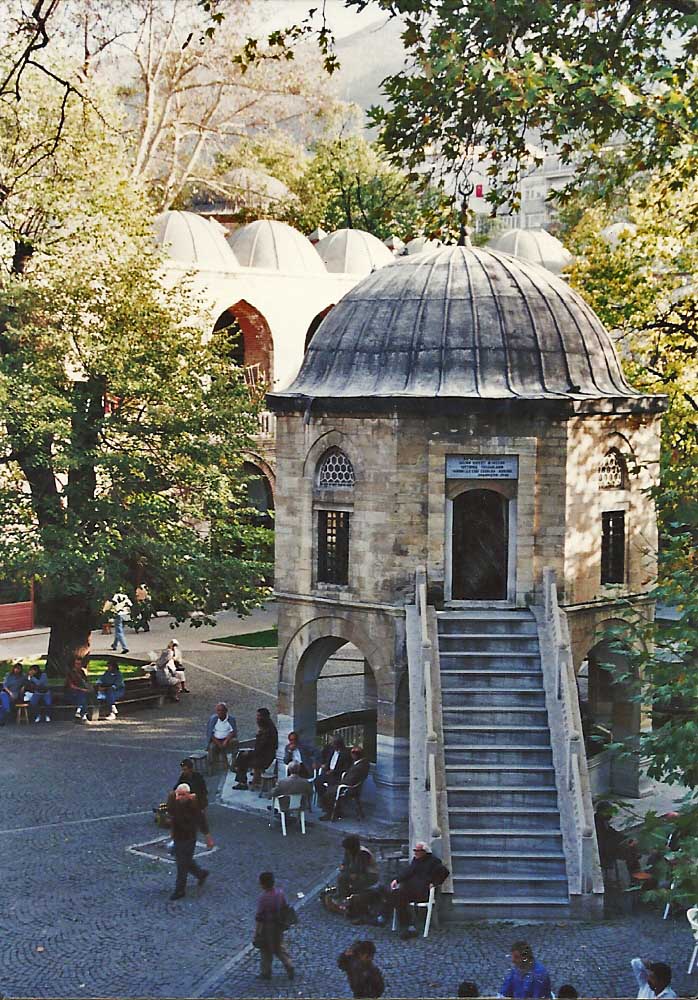

One of the policemen asked to see the camera. “Which picture did you take in Ҫankırı?” It was this one.

He frowned and passed the camera to his colleague. They went through the entire gallery, several hundred pictures of villages, flowers, cows, shepherds, signposts – all of the dross that I fill my camera with on a trip like this. The other policemen flipped through the images. After the baby buggy and the pictures of farmland, they were a lot more relaxed. They found some photos of my daughter splatting lumps of goo onto her papier mache project. This led to a conversation about children, interrupted only by the arrival of the detectives.

Two plain-clothes men had turned up. The senior one immediately took charge. He was straight out of a 1970s police drama – moustached, silver-haired and full of a sort of efficient bonhomie. His partner was thin and dour. The larger one took charge of the camera. He found the pictures I had taken of some cows and guffawed. He went through all of the photos, giving a running commentary of my travels. He stopped at the one I took in Ҫankırı. “Why did you take this?” he said. My only answer was that I thought it looked interesting. His expression eloquently conveyed his feelings about the mentality of foreigners. “The Jandarma will be here in ten, fifteen minutes,” he said.

This normally meant that that everyone would have to wait around for several hours. The seven police officers split into groups and leaned against things. The camera came back to me. Time passed. I got into a conversation about highway and railway building.

The Jandarma arrived in a Renault. There was a Master Sergeant and a lad who looked like a new conscript. The sergeant was stocky and had such an air of being in charge that all authority immediately passed to him. The larger detective told the story, the policeman in charge repeated it and I said it all again under questioning from the sergeant. The camera was called for and once again, the entire gallery was scanned. The sergeant found a picture of me with my wife and daughter, all with carrot sticks in our mouths like sabre-toothed tigers. There was general laughter and the tone of the meeting became almost convivial. He went back to the photo I had taken in Ҫankırı. He enlarged it and scrutinised every pixel. There was nothing to see. It was just a very bad picture.

It appeared that a sentry in Ҫankırı had been a little overzealous. It was probably the atmosphere of pre-election something-about-to-happen but he reported that I had photographed the Jandarma post, an act with sinister connotations. There was a discussion, then the Master Sergeant turned back to me and delivered a stern lecture about being careful with cameras in Turkey. He gave the camera back and bid me farewell. I shook hands all round and drove off very carefully. I did not ask to take a group photo.

Posted May 5, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

This was getting some proper maintenance.

Posted May 5, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

In March 2014, a roadblock was set up in Ҫankırı with the express purpose of stopping me because I had taken a photo.

In Ҫankırı, there used to be a steam locomotive maintenance programme. This is what remains of it:

Posted May 5, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Posted May 5, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

« Previous Entries Next Entries »