In the mid-1980s, I met with a bunch of like-minded Australians to drink beer and boast of adventures in wild places. We all liked to spend our holidays carrying enormous packs, rehydrating food over a Trangia and sleeping on the most inaccessible crags.

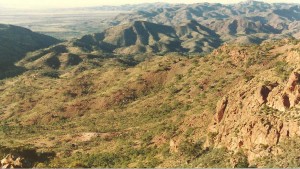

The man in whose house we were meeting won the boasting competition by showing slides of an area of the Australian bushland that was totally new to me. It was recognisable as the northern part of the Flinders Ranges in South Australia. I had been rock-climbing in Arkaroola and worked on an ecology project in Chamber’s Gorge involved in analysing the remains of animals in owl pellets. I didn’t expect anywhere in the area to surprise me. The key constraint for camping in these places was water. At 2 litres a day per person, hiking 5 days away from a water supply meant an extra 10kg added to your pack at the start of the walk.

In terms of wilderness survival, what this man showed us was gold: deep, permanent water in non-porous granite. His slides showed beautiful country, colourful birds and flocks of yellow-footed rock wallabies, all watered by those improbable waterholes.

He wouldn’t tell us where it was. Every inquiry about getting there was met with an evasive remark about finding it ourselves. In those pre-internet times, I had the ultimate resource for doing that. In an early incarnation as a Geology teacher, I had obtained a full set of geological maps of South Australia. These were like the excellent Lands Department topographic maps that hikers normally used, but with the surface stripped back to show the detail and underlying reason for what lay on the surface.

The waterholes were very clear – on a section of very old rock on the Mawson Plateau marked as ‘Geological Reserve’ and ‘Prohibited Area’ on the topographic maps. This usually meant high-quality uranium ore in the vicinity. Going there without the express permission of the government was against the law. Presumably, this was why our slide-showing friend was wary of telling us where he had gone.

As soon as summer holidays began, I was up there with my little Ford Laser and girlfriend, having promised her that this would be an adventure worth the trouble. Just before leaving Adelaide, I had bought a state-of-the-art military rescue service compass and plotted out a rough course. I drove up to Paralana Hot Springs, where subterranean nuclear processes heat the water to 57⁰C. After a nice footbath, we donned packs and headed up the escarpment onto the plateau.

After half a day’s walk, we were at an excellent vantage point for taking bearings. I took my lovely new compass out and placed it on the map. The needle didn’t seem to be facing anywhere near north. I turned the compass. The needle seemed jammed against the bottom of the casing. It didn’t work. The geological maps showed large reserves of iron ores. A decent helping of magnetite just underneath us seemed to have put the compass out of action.

It seemd to be fairly easy to work out where we were going from the map alone. My sense of direction was good back then before I moved to the northern hemisphere and it became useless. On we went. At the end of the day, we had the tent up and were looking east over the plain to Lake Callabonna. As the sky darkened, we cradled that first enamel mug of billy tea and waited for lights to appear. None did. Visibility had been excellent so we could see all the way to the horizon. When night fell, there was nothing – no homesteads, no car lights, no sign of humanity. For the whole trip from leaving Paralana to returning, we saw no signs of people at all, not a footprint , cigarette butt, a sweet wrapper.

We did see a nightjar, engaged in some kind of continuous circular manoeuvre, possibly for feeding. My girlfriend labelled it ‘The Mental Bird’. Euros clumped around the tent at night. When we crawled out of the tent in the morning, the euros would look startled and hop away a little. Then they would feed for a while. Before long, it would become too hot for them and they would disappear into the sparse vegetation. It was too hot for us too but off we would go, sighing over our meagre water ration and getting ready to sweat. Passing between two boulders to the edge of a cliff, I was confronted by the sight of a wedge-tailed eagle, two-metre wide wingspan spread like a crucifix. It was so close that I could almost touch it. I saw its glaring yellow eye sight along its beak at me, then it rose, wings immobile as it rode a warm current upward. I saw it moments later, sixty metres up and rising. I must have caught it at the beginning of its hunting ascent.

In the middle of the third day, we reached the first of the permanent waterholes indicated on the map. It was dry. So much for the water-retentive properties of impermeable granite. It seemed that the evaporative properties of the sun had beaten them this summer. At this point, I had to make a decision. I had only brought enough water for four days. If we went on and camped on the plateau that night, it would mean that we would run out of water on the way down and an injury or another emergency might be catastrophic.

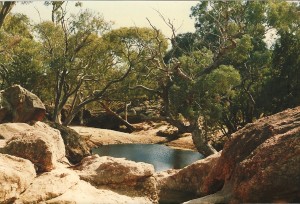

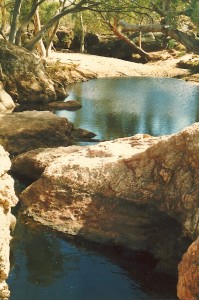

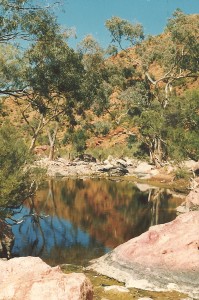

Still, we went on. We lowered our water consumption. It was ridiculously hot. Even the lizards were underground. There was a big waterhole marked on the map at the junction of two dry creeks. We reached it in the evening. We saw the trees first. There weren’t any trees of any size anywhere else on the plateau. This was promising. When we got there, it was a sort of heaven. A big stretch of water surrounded by flat rocks. Cool, blue water in a grove of shady trees. Tiny birds fluttering among the branches. The temperature seemed to drop from blast furnace to merely hot.

We were in the water immediately after our first drink. No billionaire ever had a better dip in his designer pool. We lay on the rocks drinking delicious water. That night, there was a continual movement of kangaroos and wallabies to and from the waterhole. The place was hugely populated and we had seen nothing but wedge-tails during the day. The rehydrated Vesta curry tasted good that night.

Next day we made our way up the main creek. A new waterhole seemed to appear whenever we wanted a rest. It was unlike any other day of walking I have had in Australia.

Of course, I got lost on the way down. With some of the ‘permanent’ waterholes missing and with every rocky outcrop looking more or less the same, my scheme of using the map alone for navigation had drawbacks. We came down the escarpment too far north and were wandering through unfamiliar valleys until we realised that we had gone wrong.

Fortunately, visibility was high. We went back a bit higher and scanned the lower ground until we found the green oasis of the hot springs. We had plenty of water so we found one more gorgeous campsite. That first mug of bush tea as the sun goes down, with a view over that unmistakeable Australian wilderness with nobody for hundreds of miles around… Nothing like it.

Posted April 4, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Posted April 4, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

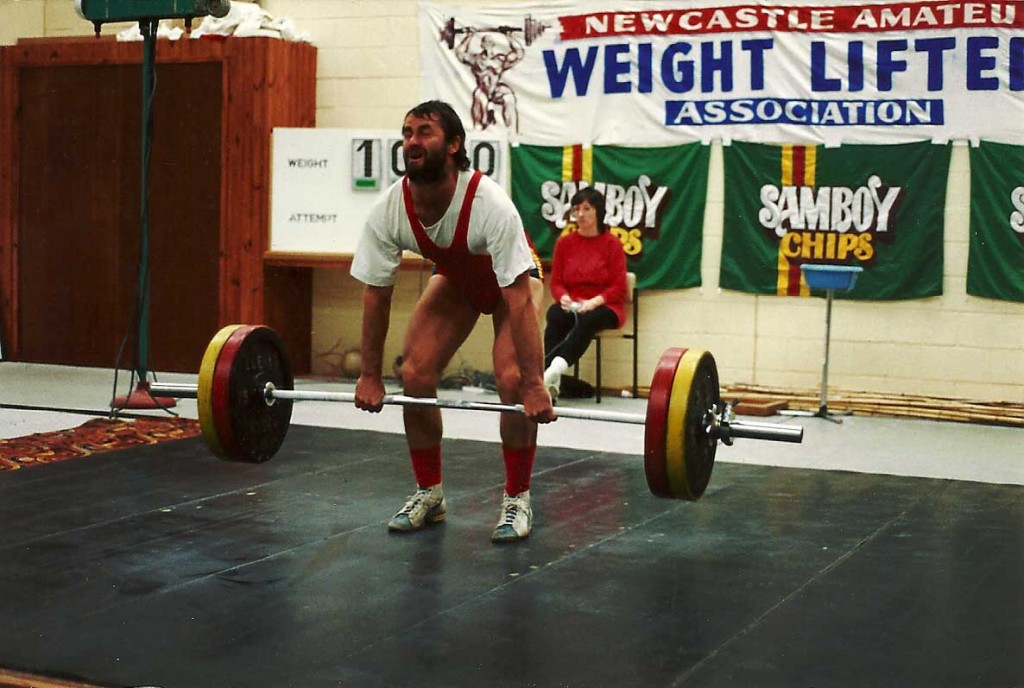

I lived in Adelaide, South Australia. The competition was in Newcastle, New South Wales.

I nearly went to sleep between the snatches and clean-and-jerks. I had to have a shower to wake myself up.

This is my first clean.

Not my most successful competition.

Posted April 4, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Posted April 4, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

I ran over the poor creature at night. I saw it just as it went under the car. I stopped and stared at it. Everyone asks whether I got a puncture. No. I don’t think those spines are up to punching through a steel radial.

So there I was, staring at a roadkill monotreme and feeling guilty. It didn’t even look injured. Just dead. I picked it up and put it into the car, not having any idea what to do with it. Into the freezer it went.

By the end of work the next day, I had decided that I might as well stuff it. It looked straightforward. Any mistakes I made with the skin would be covered up by the spines.

When it was thawed, I ran the scalpel down the centre line if its belly and made the cuts along its legs. So far, so good. At this point with a normal mammal, the skin comes off the body like taking off a glove. The difficult areas are the feet and the head.

Not with the echidna. I slid my hand between the skin and the membrane, expecting them to come apart easily. They didn’t. Each of the spines had a root that went deep into the animal. Each one had to be dug out individually. There were hundreds of them.

After an hour of digging, I stood back and had a look at my progress. It was a horrible mess. I had torn the skin in places. It would need sewing and, on a skin like this, I wasn’t looking forward to it. It occurred to me that it might not be worth going on. I thought of how I had ended the life of the poor, innocent echidna and kept going. At least I could make some kind of memorial to it.

When I finished, it was late at night. I salted the skin, rolled it and packed it in plastic. Then I went home. The skin stayed in the freezer at work for over a year. My last act on leaving that job was to take it out and place it, as gently as I could, into the skip.

Next Entries »