Samarkand

Posted February 26, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

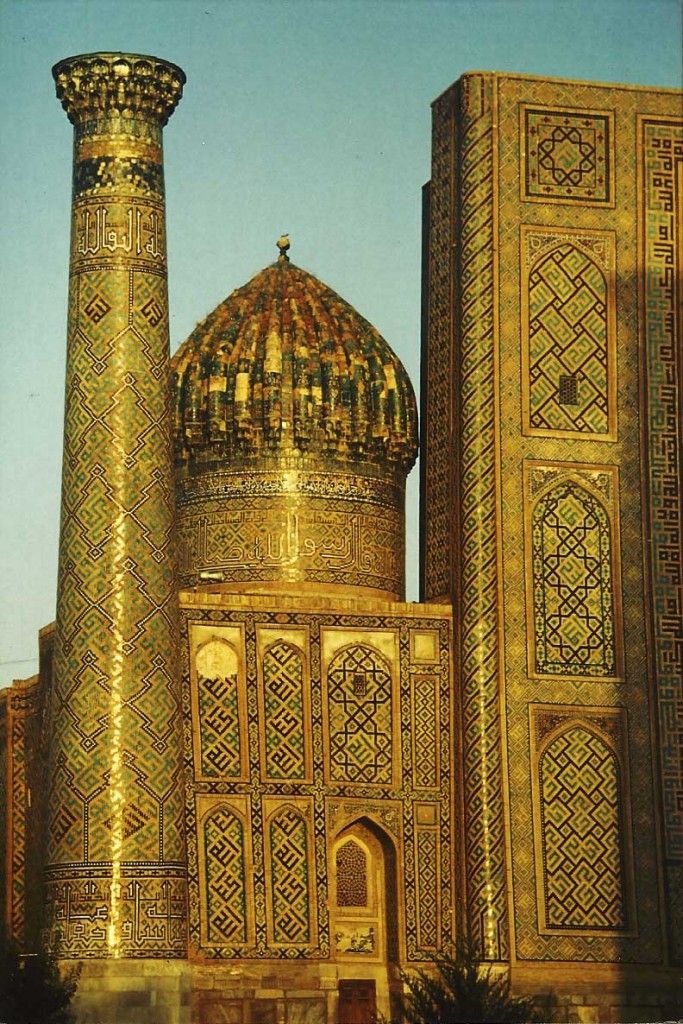

Registan, Uzbekistan

Posted February 26, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

When the Soviet Union fractured in 1991, the new Turkic republics immediately celebrated their new status by opening flights to Turkey. As I was living in Istanbul and was on holiday, I booked myself a flight to Tashkent in the first week of available travel.

The plane was a standard Tupolev still painted in Aeroflot livery. I stepped off into a baking Uzbek summer and followed the line of Turkish businessmen into the immigration hall.

As I waited in line, I realised that I was the only non-Turk. The immigration official looked at my Australian passport and tried to reconcile what he had heard about Australia with the stained old pack which constituted my luggage.

“Present?” he asked hopefully, holding out my passport.

I had no idea what would happen if I decided to be ungenerous. I peeled a US five dollar note out of my wallet, placed it inside my passport and handed it back. He stamped my passport delightedly and jovially shoved me into the country.

The country was closed. It was a Sunday and the Soviets appeared to have closed everything on Sundays. Things hadn’t yet got around to being Muslim again. What this meant for me was that there was nowhere open to get food or change money.

I strapped my unnecessarily heavy pack on and blundered into the centre of town. There was a multitude of Soviet-era statues and items of public inspirational art. I was photographing a piece of this when a man in uniform rushed up and began shouting fiercely at me. He asked me a question and my response told him that I was not just a weird-looking Uzbek, but a bona fide foreigner.

“Present?” he asked hopefully. But I had grown wiser in that hour and he left empty-handed, going off to bully other unfortunates who ventured too close to official statuary.

Eventually, I went to the Tashkent Hotel where the magnificently efficient manager changed some of my dollars with roubles from her purse and rented me a sombre room so I could and continue my exploration unhindered.

Several things became apparent. I was foreign so everyone thought I was Russian. The little Turkish I spoke could be understood. Women wore the brightest colours imaginable. Gold teeth and eyebrows meeting in the middle were the height of chic. Also, I began to realise that a US dollar could buy an enormous amount and the Tashkent Hotel manager had got herself a good deal from me.

Tashkent turned out to be a spacious city with wide, tree-lined streets, an overdose of Soviet monumentry and an airport that I knew how to find. I booked myself a ticket to Samarkand for the next morning.

The next day saw me standing next to a small, twin-prop plane with a man named Ed who turned out to be an economist from Notting Hill and the only other English speaker I met in Uzbekistan.

“Don’t get on yet,” he advised, indicating the refuellers chain-smoking Russian cigarettes on the overhead wing of the plane while pumping Avgas into the tanks.

“All right,” said Ed when the refuellers were safely out of fireball range. “This is probably the best place to sit if you’ve got luggage.” He slung his pack into the front of the compartment and sat in a seat with loads of legroom.

“It’s got all its windows,” he commented as we taxied past an endless flock of ancient biplanes and rattled into the air. Apparently the airline did not always deem it necessary to replace a window immediately because the plane did not need to be pressurised to fly at low altitudes.

We landed at Samarkand without incident and headed to the Zarafshan Hotel, which was said by someone in Tashkent to be clean and inexpensive. Surprisingly, it was.

“You’re a student, aren’t you?” Ed glanced at my wallet. “What’s that card?”

“My Turkish teacher’s card.”

“It’s your student card here.”

The price for a room fell to less than a tenth.

We discovered that the hotel was the temporary headquarters of an enormous international puppet festival. Performances took place in the huge Soviet-era hall beside the hotel but in the evenings, the Zarafshan became a palace of puppeteers.

We met the Turkmen National Puppet Theatre in a restaurant near the Registan. We had finished the customary mountains of pilav and tandir-cooked meat which we had sent on its way with a bottle of champagne each and were at the vodka stage, when a young woman with a slim figure and 100% gold teeth appeared at our table.

She introduced herself as Zaineb. She spoke a form of Turkish that I could understand enough of to realise that we were being invited to join the rowdy table at the back of the restaurant. We looked around and saw nine gold-mouthed people raising their glasses and beckoning us over.

Grabbing our Stolichnaya, we followed the woman to the table and learned that all these people were puppeteers or stage crew from in or near Ashgabat. The man who seemed to be the leader was Karim, thick-set, heavily-moustached and gregariously drunk. He had recognised us from the Zarafshan and decided that leaving us sitting on our own would be letting down the Turkmen reputation for hospitality.

They had performed that day; a technically difficult piece involving their update of a traditional Turkmen story. We learned that in central Asia, puppetry was a mainstream art form, considered as a real alternative to theatre with human actors. There was a long and respected tradition of puppeteering as a cultural constant. Karim said that it was so ingrained in their culture that the most popular current childrens’ plays had also been his grandparents’ favourites.

They had had a good reception today but as Zaineb said, so did those fools from Canada who wore bear suits. Karim thumped the table.

“There is no proper critical evaluation here,” I think he said. My Turkish always became much better in my mind when I had been drinking, but perhaps I was failing to take into account the subtleties of the Turkmen dialect. “We could come here and do an unrehearsed show like schoolchildren and still we would receive a standing ovation.”

“What are you saying, Karim?” One of the men on the other side of the table spoke up. “This is not some sort of competition. We have to realise that we have the benefit of a great tradition in puppetry and if people of other countries who do not know the greatness of this art come here, it is our duty to encourage their development.”

Karim stood up with his vodka bottle. “Mahmud! This is very noble of you. You always see the best in everyone. If someone has no talent, you say, ‘It is good that he tries’. I f someone forgets his lines, you say, ‘His voice was very good’. If a puppeteer fails to make his character leap from the limitations of its strings to become reality, you say, ‘He works very hard’. You must see that people who do not have the Talent should not be doing puppetry at a major international festival.”

I’m fairly sure he said that. I was watching Zaineb. She was watching Ed and me. The concept of gold teeth was no longer a strange, alien deterrent. The argument raged around us as this quieter drama opened.

“No!” boomed Karim. “We must strive to push aside the frontiers of the dramatic arts!” He had another swig. “It is not enough that puppetry should be an equal partner with the other so-called dramatic arts. With our art we are not held by reality. We build our characters. We, as their creators, can make them soar, far beyond…”

“Let’s go back to the hotel,” said Zaineb firmly. “She linked arms with Ed and me. “Our visitors do not wish to hear us arguing about how bad all puppeteers except the Turkmen are.” She steered us out of the restaurant and straight into a taxi. How had she known it was there? Who paid the restaurant bill? What was it like to kiss a woman with metal teeth?

Ten minutes later, the restaurant conversation was continuing in a small hotel room. “Why is it,” demanded Karim, “that when the Uzbek organisation wants to have a festival that it has to invite someone from Canada, someone from the United States, someone from all of the countries with big names just because they are from those countries?”

Mahmud countered with, “Is it not the best thing that people from these countries see superior performances so they can be influenced by them and the standard of puppetry throughout the world can be improved?”

Zaineb sat between Ed and me on the bed and leaned back until she was resting against both of us. “I love the art of the puppet,” she murmured, “but I prefer other things at night.” I could feel her breast against my arm. She smiled. I could see why central Asian people found the golden mouth so attractive.

“And what do you think of this, Zaineb? You have always been a purist about the sacred art of the puppet.”

“Karim, I think as you do. But this is not the time.”

“It is always the time!” Karim gesticulated alcoholically. “There is no time that we should not be fighting for the advancement of the best art in the world.”

“This is what I am saying.” Mahmud stood up. “We know that our traditions and skills give us the best puppet theatres in the world! We must take these opportunities to allow people in other countries to share our interest and improve themselves. Besides, who knows? They may have worthwhile things in their own traditions that we could learn from.”

Zaineb snuggled closer to us and pressed more of her alluring body against Ed and me. “Things are about to become bad. Perhaps you will need to go soon.” She passed some cards to me. “Make sure you come to this show tomorrow night. They,” she indicated the sparring Karim and Mahmud, “will have to be sober then so there will be none of this.”

“What things, Mahmud? You have seen the crudeness of their puppets and the insensitivity of their puppetry. Their government gives them money to come here and show us that they have no talent. What can we learn from this?”

Mahmud smirked. “We can learn that if we go to Canada, their government will have something worthwhile to give money to.”

“Again you say this!” Karim was incensed. “It is always money for you! Now you are saying we should go to Canada and leave our wonderful traditions. We will be prostitutes for the money. We will perform for philistines who have no appreciation of what we do.”

“But we will be able to do something worthwhile because we will have the things that we… that you always complain that we do not have. We will have the freedom to practise our art as it should… as it must be done.”

Karim had started his rebuttal long before Mahmud finished. He stood in front of him and shouted, “And we will become like them. All appearance and no soul. The art will die in us. We cannot…”

Zaineb had propelled us off the bed and into the corridor with subtle but authoritative movements of her body. She kissed us both softly on the cheeks and murmured, “Come and see us tomorrow night. It will be a good show.” She flashed a rich smile before gliding back into the tense room.

“What did she say?” asked Ed.

“She invited us to their show tomorrow night.”

“Really?” Ed looked surprised. “Just going on non-verbals, it looked as if she was asking us to be her partners in the World Orgy Championships.”

Ed and I rose with our characteristic vodka hangovers to find the car we had ordered with such foresight waiting for us. It was a black Volga and we had said that we wished to go ‘somewhere south’. We wanted to go towards Termez on the border with Afghanistan but, realising that it was too far, vaguely planned to go somewhere on the way.

Viktor from Intourist was waiting for us with a map.

“Do you want to see a kilim factory?”

Ed and I looked at each other.

“Yeah. Why not?”

“Good. We will go to Shakrisabz.”

Viktor piloted the Volga past the enormous courtyard of the Registan and the great cemetery of Shakhi-Zinda, then through suburbs of low-walled houses and into the surrounding farmland. We headed towards a distant row of mountains to the south.

The land ran out of water and lapsed into semi-desert. Ed responded to the scenery by slumbering peacefully through it. I would have done the same if Viktor had not felt compelled to point out interesting features of the landscape from time to time.

“House.”

“Tree.”

“Rock.”

After a while, we drew closer to the mountains and the road began to wind through the foothills. Viktor grew more animated.

“Sheep.”

“Village.”

“Thing.”

The last expression was prompted by a small animal that ran across the road. Neither of us knew what it was.

Ed woke up and stretched out his tall frame in the back seat. “Where are we?”

“Here,” said Viktor logically.

“We’ve reached the mountains,” I said obviously.

“Have a look at that.” Ed pointed at something to the right. A majestic shepherd with a huge moustache and a highly decorated overcoat was leading a flock of hundreds of sheep towards the road. Muscular, capable-looking dogs harried any outliers back into the mob. The shepherd waved at our Volga, his smile revealing a prominent gold incisor.

We rushed past, feeling that we had seen something of the real Uzbekistan. How had Ed known to wake up just then?

The winding road reached the top of a pass and we looked forward across an immense view of rocky, scrubby hills. A line of trees in the distance showed where a river was. In a few minutes, we were driving next to the river and following it down onto a cultivated plain. The frequency of houses began to increase.

“Shakrisabz,” said Viktor proudly.

Ed and I looked around. It seemed an undistinguished place. The roads were lined with the compound walls of low houses. There were a few trees dotted about. We rounded a corner and an enormously tall ruin sprang into view. This was the remains of Ak Saray, the white palace built by Timur in the town of his birth. The visible remains were the two immense pillars on either side of a collapsed arch. Their position in an overgrown field in an otherwise vacant lot gave them the appearance of an abandoned industrial plant rather than a great architectural treasure.

Viktor took us to the Intourist office. He traded some banter with a heavily made-up local girl behind a desk and collected a sheaf of papers. “Street card,” he said, handing us a map. “Three,” he added, pointing at his watch. He gave us a satisfied smile, went into a back room and lit a cigarette.

Ed and I walked outside. A little way down the main street was a market, filled with people dressed in bright, primary colours. I bought some garlic from a man as an excuse to stand there long enough to ascertain that he really was dressed head to foot in scarlet.

A large and impressive mosque loomed over the scene. In the corner of the market closest to the mosque was a stall selling the square, maroon hats that Muslim men wore. I bought one of these, jammed it on my head and went into the mosque courtyard.

A man who seemed to be in charge nodded approvingly at my headgear. The courtyard was freshly swept. Some pink flowers spread across the climbing foliage that covered one side of the wall. The sounds from outside were muted and remote.

The wooden veranda of the mosque made a cool patch of shade in which bearded men who had made the Haj to Mecca sat peacefully. They smiled serenely back at me when my eyes met theirs. Some small girls played in a corner of the shade. Their quiet voices accentuated the calm.

I looked towards the door of the mosque. One of the old men smiled and waved me in with a small movement of his head. I took my boots off and slipped past the door covering into the dark, still interior. Shimmering rays streamed from the high windows, giving a mystical light to the atmosphere. A deep chanting came from one corner where a bearded man sat with a Quran on the wooden stand in front of him.

“Change money?” hissed a small boy who materialised beside me.

Viktor was asleep in the car when we returned to Intourist. Ed jumped into the car and slammed the door, but Viktor slumbered on. I checked my watch. Well after three. I shook our driver awake. His eyes opened. He moved seamlessly into wakefulness and clicked his seat to upright.

“Kilim factory,” he said brightly and lurched the Volga into the industrial suburbs of Shakrisabz. The kilim factory was a giant warehouse with rows and rows of vertical looms, each with a pair of women whipping shuttles of wool through a grid of fibres. The colours were a celebration of eye-watering chemical dyes. Purple, orange and green predominated and no contrast was too hideous to put into practice. Ed and I wandered about, trying to find something that came some way toward matching our tastes. Viktor chose this time to ask Ed and I if we were married. It turned out that Ed wasn’t.

A whispering sound made itself heard. It gathered momentum and began to sound like a gale through autumn woodland. Suddenly there was silence. We turned to see a faceless figure approaching through the forest of looms. It was humanoid in shape and clad in the vivid textiles that were used for the most impressive clothing in Uzbekistan.

The figure headed for Ed with a slow, sinuous gait. There was a change in the top part of the shape and a pair of liquid black eyes could be discerned. This was a maiden in full courting mode. From my point of view as an observer, it was fascinating. Ed, the target, later described it as frightening. The girl wore a golden headdress with a fringe of coins over her eyes. A veil covered her hair but artful dancing movements revealed the gleaming sea of black tresses beneath. Her carefully trimmed monobrow and truly stupendous eyelashes framed those huge eyes. Occasionally, her golden smile proclaimed the fact that her family had some money.

The girl shimmered up to Ed and began a complicated dance around him, nicely choreographed to display her sinuous body and those amazing eyes. Suddenly she stopped, fell at Ed’s feet and waited, completely motionless. Viktor sidled up to me. “Does he want her?”

The room was totally silent. I could see Ed mouthing, “What do I do now?”. I picked my way between the weavers and approached Ed. “What’s going on?” He looked desperate.

“They’re asking whether you want to marry this girl.” I don’t know why I whispered. Nobody but Ed had a clue what I was saying. Ed was staring at me.

“Of course I bloody don’t. Let’s get out of here.”

I put a sad expression on and headed back to Viktor. I mustered up some of my best Turkish to say something like, “Although this man is not married, there is an understanding between his family and that of a girl. He is not free to marry.”

Viktor called something out. The silence evaporated into an excited hubbub and the girl stood up and grinned at Ed before taking off her costume and sitting down at one of the looms.

In the Volga on the way back to Samarkand, Ed lay back in his seat. “Do you think it could have worked?”

The Turkmen performance was dense and sombre. No concessions were made to the children in the audience. The puppets were menacing, heroic, vengeful. This was a traditional epic with themes of war and death and the hopelessness of one against many. The contrast with the Canadian effort we had seen the night before was stark. That one had featured cuddly bears and posturing Mounties.

The Turkmen puppets acted out their doom. There was victory of a sort but no celebration. The hero died after a weary speech. There was silence, then a passionate standing ovation. Our friends from the night before appeared on the stage. Karim, Mahmud and Zaineb were in the centre of the group of performers. They bowed humbly with no sense of self-congratulation.

Karim started again in the hotel room. “One of those Canadians came up to me after the show. ‘You were great,’ he said. He didn’t even know which parts I was playing.”

“You were great, Karim,” said Mahmud. “Let him pay tribute to you when you do something admirable.”

“He doesn’t know what’s admirable. I saw him pretending to be a puppeteer. He put on a bear suit and jumped up and down.”

Mahmud laughed. “I saw that. Still, let him recognise you as a sublime performer.”

They might have been saying that. I wasn’t concentrating. Zaineb had cornered Ed and me on a bed. We had drunk the usual relaxants of champagne and vodka. Zaineb spoke to me and looked at us both. Her gold smile was seductive. The performance was over. This was the time for kicking back, relieving tension. We were all leaving tomorrow. If there was anything to be done it needed to be done now.

Zaineb asked the important question. “Are you married?” I nodded. She disengaged from me with a fluid, almost imperceptible movement. “Is he?” I shook my head. Zaineb seemed to wind around Ed like a soft, welcome python. I felt a stab of regret. I had done the right thing. I glared enviously at Ed.

“What’s she saying now?” Ed seemed bewildered at the improvement in his fortunes.

“I told her you’re not married.” I grinned and stood up. I was irrelevant to the scene on the bed now. “Remember, any funny business and she’s your responsibility for life.” I made for the door.

“What?” I heard Ed’s voice. “What do you mean?” I looked back to see him sink beneath a wave of Zaineb.

Hours later, I heard Ed struggle into the room and make his blundering preparations for bed. There was a moment of quiet and I became aware of Ed looming over me.

“Bastard,” he said.

Posted February 26, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

mosque, Be'er Sheva

Posted February 26, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

The place identified as the site of the manger

« Previous Entries