Earlier in this section, I discussed the mermaid as the acceptable face of ichthyophilic practice in the second millenium BCE, the time of Homer. However, there is ample archaeological evidence that men have been disguising their physical liaisons with denizens of the marine world for at least seven thousand years. People have always lied about the attractiveness of their short-term sexual partners. In the modern world, a gentleman will simply steal a pretty girl’s Facebook profile photo and make a knowing face as he displays it on the screen of his device for the edification of his friends. In pre-dynastic Egypt it was not so easy to convince one’s mates that, despite visual evidence, one had not just had sex with a fish.

Images were more time-consuming to make and more permanent. Representations were far less specific than today. Rather than the biometric precision demanded of 21st century imagery, Neolithic artisans were generally employed to obscure identities – sometimes even species.

In a classic case of obfuscation by art, a denizen of Upper Egypt portrays his lover in an ambiguous manner. With technology in a pre-representational state, nobody would be expecting Rodin perfection in a quick clay statue of the girlfriend. “A bit like this,” he might say, spreading the clay of the pectoral fins to something resembling arms and kneading the pelvics to give a hint of breasts. “Oooh,” his audience might respond, discerning a hint of femaleness in the object of desire and hence allowing the most far-fetched story some credence.

Two millennia afterwards, a revolution in artistic technique made it difficult to rely on undeveloped technique or poor workmanship By 2800 BCE,a complex mythology was in place involving a myriad of nymphs, naiads, nereids, oceanids and the like. These were seducers and/or seduced, constantly ravished by gods, pursuing mortals and bearing hybrid children.

This, of course, meant a ready set of excuses for men caught having sex with piscatorial partners. No-one who was anyone could go through life in the right circles without a set of drinking stories of his dalliances with various euphemisms for fish. The representation of these in art led to the stylised Louros figurines from the eastern Cyclades.

In this example from the British Museum, one may readily recognise the influence of the more crude predecessors (fig 1) but the clean symmetry of this marble work brings to mind the symmetrical perfection of Brancusi’s work.

This is a work of art from a culture confident in its artistic superiority, its developed religious iconography and its pride in having sex with fish, their contact with the gods.

A little later in northern Mesopotamia, the large river fish of the Euphrates were frequently called on for their sexual services by the agricultural denizens of the region. In this case, the depiction of the mermaid was turned in its head in a rather Magrittean manner. The large eyes and streamlined head of the fish were valued for their beauty. Hence figurines of these ichthyan objects of fantasy were represented with human bodies and fish heads, although the heads were usually crowned with improbable concoctions of millinery and hairstyle.

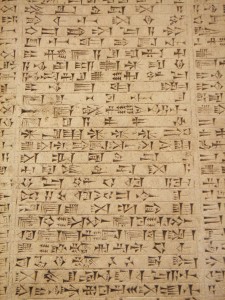

This cuneiform inscription, carved in Sumer in about 2400BCE, gives a rare insight into a society in which the manner of conducting sexual liaisons with fish was inscribed in law.

The text resisted translation for centuries after its discovery (possibly because it was difficult for scholars to believe that the meaning they decoded was the correct one) but current interpretations reveal the following injunction:

…HE WHO IS TO LIE WITH THE BALCINUS (the Mangar, Luciobarbus esocinus (Heckel 1843), a large fish that can grow to a length of 220 cm) SHALL FIRST MAKE OFFERINGS TO THE GODDESS INANNA AND, IF THE PORTENTS ARE AUSPICIOUS, SHALL ENTER INTO SYMBOLIC MARRIAGE WITH THAT MOST AUGUST AND FERTILE GODDESS. THE ISHMERTEZ (procurer/matchmaker) SHALL BE DISPATCHED TO OBTAIN THE FISH THAT HAS BEEN CHOSEN AS THE PARTNER…

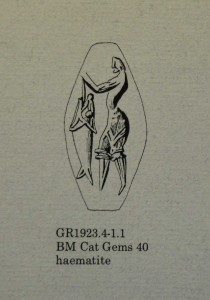

This tiny haematite object in the British Museum is part of the seal ring of one of these procurer/matchmakers. The line drawing shows the impression that the ring would leave on the seal. Obviously, the legal constraints on the activities of a person in this position were both specific and comprehensive. One would not wish one’s procurer to release any details of one’s extracurricular pursuits. It may sound odd to have a sexual activity virtually required by a man in the upper echelons of society yet needing to be hushed up. I would offer as comparison the situation in England, especially from the late Victorian period until World War II, when a hint of homosexuality would end a career in public life yet joining in with the all-male rogering activity at a prestigious boarding school was de rigeur.

This unusual item was found strapped over the genitals of a man in a cemetery in the Jordan Valley. It dates from about 1300 BCE, a time when this area was under Egyptian administration. Clearly, this man had an eye on the afterlife. Why should death keep him from his favourite pastime? He has kept the fish handy in the event that his reincarnated self will carry on his taste for poikilothermic sexual partners.

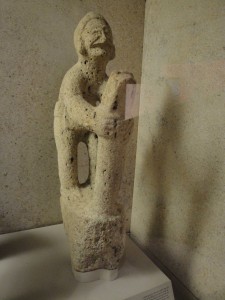

I finish this survey of pre-classical archaeology with the definitive representation of a man having sex with a fish. This was evidently carved during a period of history in which verisimilitude trumped the rather aspirational imagery of the mermaid. A man, still grasping his cold, damp partner, experiences that moment of post-coital horror when he realises what he has done.

This is the true story of sex with an enormous fish. An unsatisfactory coupling followed by moist regret. Small wonder that the self-deception of mermaid imagery has been employed for millennia. Men in the throes of priapism have an unrivalled capacity for employing fantasy to hide from themselves the reality of the particular item into which they are inserting themselves.

Categories: Uncategorized | No Comments »