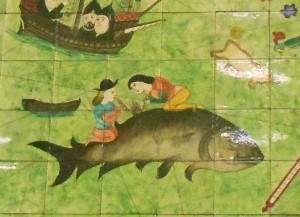

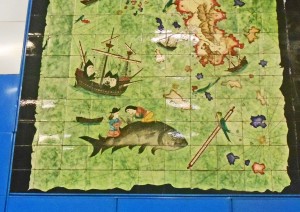

This is a section of the 1513 map by the great Turkish cartographer Piri Reis, probably the first credible attempt at a representation of the earth’s land masses. Part of it is shown here, reproduced as a tile mural on the wall of Levent Metro station in Istanbul. The original is in the Topkapı Palace Museum. It shows an enormous fish in polar seas, receiving the rather strange attentions of two crew members of a nearby ship.

Intercontinental travel was uncomfortable and time-consuming. The lack of sex was felt acutely by most sailors. Whilst men in some navies would temporarily abandon their prejudices against same-sex relationships, this could not be done in Turkish ships. The strict Muslim taboo against homosexuality and the threat of draconian punishment combined to create the need for other outlets.

Inevitably, this meant marine fish. Turkish ships were well-provisioned and it was common practice to throw excess meat overboard to encourage fish to follow the ships. On nearing a new land mass, a flock of attendant fish could easily be built up by increasing their food supply in the proximity of the ships. Libidinous mariners could satisfy their desires with these fish in the normal way.

Very large fish were especially welcome. The pictured specimen appears to be a kind of cod, probably a groper. These are territorial and would not have followed the ships. Instead, contemporary maps would have marked the locations of populations of fish that would be amenable to making themselves available in return for food.

In winter or in higher latitudes, the satisfaction afforded by coupling with an enormous fish would be reduced by the temperature, both of the environment and of the body with which one was copulating. In Piri Reis’s depiction, the well-swaddled crew members of a sea-going trading ship observe as the ‘cockle-warmers’ kindle a fire on the fish’s back.

In this exercise, the warmers would row to the fish in a small boat containing the tools of their trade. The fish, accustomed to the procedure by now, would approach and receive a plentiful supply of food. In return, it would remain stable in the water to allow the cockle-warmers to place a blanket of asbestos onto the fish’s dorsal surface and make a fire on it. This would not burn the groper but it would raise its blood temperature to a level at which it would feel a little more like a human partner to the thrusting matelot.

The fire would also provide some welcome post-coital warmth for the fish. With its body temperature increased to somewhere close to the optimum temperature for the enzymes involved in cellular respiration, the fish would have been more efficient hunters and, more relevant in terms of evolutionary development, been more active in finding and pursuing sexual partners. Hence, some reproductive benefit would have resulted from the initial behaviour of the fish making itself available for congress. As those that remained coy were more likely to be killed for food, it would appear that during the time of Piri Reis, fish that had sex with people were more likely to pass their alleles to future generations than those that didn’t. It is possible that the way to the present-day’s proliferation of sex with fish was facilitated to some extent by the wide-ranging Turkish navy.

The practices depicted here gradually died out as more pragmatic approaches to temporary shipboard physical liaisons emerged in the late 16th century.

Categories: Uncategorized | No Comments »