This is nominally a museum (40.996124,28.928665), closed to the public and looking like being so for some years. I fear one of those official restorations (as with Iznik’s Aya Sofya) where an old building is rather insensitively roofed and becomes a sort of propaganda mosque. The first two pictures shown here are from December 1990, when the museum was open and one could see the most magnificent monastery of the Byzantine empire quietly becoming dust.

Founded in 463, this was a place with continuous chanting, where depression was a sin against God and where, if the ruling powers wanted to find some dissident noble or other, he was sure to be skulking in the Stoudion, hoping not to be blinded. It was also the centre of the 9th century Byzantine renaissance. Great works of literature, art and music came from here. Given that this was a hotspot of Christian representational art, the Stoudion’s sun went behind a cloud in the iconoclast era. After the 7th Ecumenical Council in Nicaea put icons back on the Orthodox pedestal in 787, the illuminators of the monastery went into glorious production and achieved world renown. Now only the ruined church and an unroofed cistern remain of this artistic paradise.

It was wrecked in the 1204 crusade, then recovered to survive the Ottoman conquest. Beyazit II turned it into a mosque at the end of the 15th century. An earthquake in 1894 smashed it and it has crumbled until now, when Fatih Belediyesi may do one of their radical facelifts on it. This article suggests that the official plan is to restore the basilica and turn it into a mosque. However, the timeline indicates that this transformation should already have been completed. As of July 2016, nothing appears to have been done since a holding restoration in the 1940s. This involved adding scaffolding to support the remaining bits and tiling the tops of the walls to protect them from weather damage.

It’s still an impressive beast. It’s the only existing Byzantine basilica in Istanbul except for St Mary Chalkoprateia, which is far more of a wreck. It has lovely mosaic pavements and just enough sculpture remaining to hint at marvels from the past. Check van Millingen’s pictures of the place a century ago. The church was still essentially intact although significant damage from the 1894 earthquake is evident. According to van Millingen, the roof collapsed because of ‘an unusual fall of snow’ (van Millingen p49). The fire of 1920 seems to have done a great deal more damage. These pictures from the wonderful collection left by Nicholas Artamonoff, were taken mostly in the 1930s and show a situation recognisable in today’s condition of the Studion.

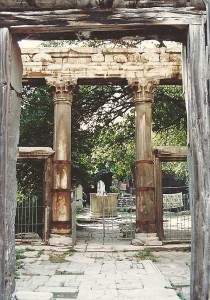

The following pictures are from July 2016. One enters from the west into the atrium. This has a marble fountain in the centre and the remains of cloisters on three sides are still visible. The atrium was used as a cemetery after conversion into a mosque. The surviving headstones add a touch of sculpture to the court.

The iron fence guarding the narthex is the one that appears in Artamonoff’s pictures from the 1930s. The narthex itself is constructed in heavy brick with a large central section and smaller bays to the north and south. The external section of the middle bay is supported by four columns with particularly nice Corinthian capitals. The falling of the western wall since van Millingen’s pictures of 1911 has left the columns on their own, supporting an elaborate and largely complete entablature. The minaret looms over the south bay of the narthex.

The interior of the church was once divided into three sections by two colonnades, the northern one of which still survives with the aid of a lot of scaffolding. The capitals are very worn Corinthian and the intricately carved architraves have been weathered to smoothness. There were once two levels of colonnade, the upper ones supporting galleries.

The large apse on the eastern side has little Byzantine about it. The Ottomans rebuilt it with some pleasantly delicate window mouldings but did not extend it so high as in the original building. The bema underwent a great deal of modification in the conversion to a mosque, particularly with regard to adjustments needed to give the mihrab its necessary alignment. There is a small crypt beneath the bema.

The floor of the nave is a highly restorable ex-masterpiece of marble mosaic. It has been open to the weather for a century and the damaging effects of the expanding roots of this summer’s weed growth can be seen. There were once playful figures of rabbits and foxes on the floor but time has erased these. One can see the deterioration in a comparison of the photos from 1990 and 2016. Records exist of the original state of the floor and it would be nice to see it returned to its glory.

To the south of the church is what remains of the cistern. This was once an elegant structure supported by 23 Corinthian columns but is now a sort of wild sunken garden. At the beginning of the 2th century, a small chapel stood to the east of the cistern. Dumbarton Oaks reports that the building was taken over by a distiller in 1944 and that it no longer exists. The site, on Mahzen Sokak, is currently occupied by a recently constructed (and apparently disused) charitable foundation building.

This building is older than the familiar cruciform shape that typifies Constantinople’s Byzantine churches. This is a basilica, built before the new rules imposed by the immense architectural authority of Hagia Sophia. There are no closed-off chapels to the sides. There are doors (now bricked up) opening to the outside at the eastern ends of the aisles. The feel of the church is more similar to the Roman Catholic St Esprit Cathedral in Harbiye than to, say, Kariye or any of the Pantocrator churches. Using a bit of imagination whilst inside the Cathedral of St Demetrius in Thassaloniki might project one into the mindset of a 5th century monk of the Stoudion.

The finest legacy of the Monastery of Stoudios is not in brick and stone; several of the products of the monks’ labours have survived in good condition. The most famous is probably the 11th century Psalter of Theodore, now in the British Library. This has been digitised and some sections of the Psalter can be seen here. The Chludov Psalter is from an earlier period in which the iconophile/iconoclast battle was fresh in the illuminators’ minds. This article analyses what amounts to a 9th century political cartoon in the Psalter.

Two capitals from Imrahor Camii, now in the Church of the Holy Wisdom in Surrey. The official story is that Edwin Freshfield saw some Turks using the capitals for 'revolver practice'. When he protested, he was offered them for one pound. I don't believe a word of it.

Artamonoff, N. (2013-2016) St John Stoudios, Istanbul. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC. Available online at:http://images.doaks.org/artamonoff/collections/show/44 Accessed 10th Jul 2016

British Library: Theodore Psalter (1066) Digitised Manuscripts: Add MS 19352. Available online at: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_19352 Accessed 10th Jul 2016

Levendig, M. (2012) Anonymous: Chludov Psalter (9th Century): Historical Museum, Moscow. The World According to Art. Available online at: http://rijksmuseumamsterdam.blogspot.com.tr/2012/09/anonymous-chludov-psalter-9th-century.html Accessed 10th Jul 2016

Mathews, Prof T. (2001) Hag Ioannes Prodromos en tois Stoudiou The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Available online at: https://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/index.htm?https&&&www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/home.htm Accessed 10th Jul 2016

Müller-Weiner, W. (1977) Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls. Tübingen. pages 147-152

Van Millingen, A. (1912) Byzantine Churches in Constantinople: Their History and Architecture. Macmillan, London. Available online at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm#Page_35 Accessed 10th Jul 2016

Ziflioğlu, V. (2013) Istanbul monastery to become mosque. Hurriyet Daily News. Available online at: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/istanbul-monastery-to-become-mosque.aspx?pageID=238&nID=58526&NewsCatID=341 Accessed 10th Jul 2016

Categories: Uncategorized | No Comments »