This church has been brought to renewed prominence by the opening of the Vezneciler Metro Station in 2014. As one surfaces on the escalator, one is faced with a perfect Byzantine church (41.013187,28.960133). The interior is lined with attractive marble and gives rise to a pleasant monochrome, appropriate for reverential activity should one be in the mood.

Although the Kalenderhane itself has been restored, it is surrounded by ruins which have presented a puzzle for archaeologists. For now, we generally use the interpretation of Matthews. This website has some excellent photos, all of which are labeled ‘Isa Kapisi Mescidi’ a name that refers to a building which lies some kilometres to the west.

The first church on the site was built in the sixth century. Its apse survives, owing to its protected location hard against the Aqueduct of Valens.

The arch at the bottom leads into the apse of the 6th century church. At left is the aqueduct, at right is the late 12th century church

The current church appears to be largely from the late 12th century although its foundations seem to be from a church of similar dimensions built in or around the 800s.

Massive brick pier from the north side of the church, possibly part of the dome support of the 6th century church

The apse of the first church is currently (summer 2017) seeing service as a dormitory for otherwise homeless men.

From the apse, one finds the entrance to the prosthesis. The two chapels either side of the central apse in the main church have been bricked up and are not accessible in the usual way. Pictures from 1914 show them to have been accessible from the naos, as one would expect.

There is something of a jumble of stonework in parts of the eastern end of the complex, where building styles of three eras intersect.

On the eastern end of the south exterior wall of the church is the entrance to a chapel. Investigations in the 1960s revealed some lovely frescoes of the life of St Francis of Assisi. These were added during the Latin occupation (1204 – 1261) in about 1250. The frescoes, together with the only surviving pre-iconoclastic mosaic in the church, are now in the Archaeological Museum.

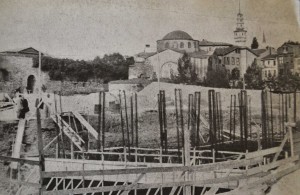

The minaret is very recent, being rebuilt during Kuban ad Striker’s restoration. Liddell reports seeing the muezzin calling the ezan from a high stone in the 1950s. The picture below from 1951 shows how much the building has changed since then. I struggled to recognise it as Kalenderhane until I looked at van Millingen’s illustrations.

Striker and Kuban carried out the definitive study of the church and its surroundings in the 15 years from the time Striker gained permission to break the lock of the derelict hulk in 1966. They have traced the identity of the main Kalenderhane church as part of a monastery dedicated to the Mother of God who Reigns in Majesty (Theotokos Kyriotissa) on the basis of inscriptions found in the church. A review and summary by Robert Ousterhoult of the first volume of their published study may be found here. The great Dogan Kuban still takes breakfast occasionally on the terrace of the Adahan Hotel.

The main church is constructed of alternating courses of stone and brick. It forms a Greek cross with semi-circular section barrel vaulting over the four arms. The scalloped edge of the 16-rib dome was restored in the 1970s and looks very different from the 1950s incarnation of the church.

The really distinctive feature of this church is the marble revetment. This includes some elaborately carved marble icon frames either side of where the iconostasis was placed.

Icon frame on the north side of the church. The arched (former) entrance to the prothesis can be seen at lower left

The St Francis chapel is in the area of the diaconicon on the south-east corner of the church.

Flanking the present-day south and north walls of the church are parallel walls that are partially destroyed. According to Matthews, these marked the extent of aisles either side of the main nave that were destroyed in Ottoman times.

Matthews, Thomas (2001): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Available at http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/html/Byzantine/ Retrieved 16 Oct 2017

Müller-Weiner, Wolfgang (1977) Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut) Verlag Ernst Wasmuth Tübingen

Ousterhout, Robert (2000): Contextualizing the Later Churches of Constantinople: Suggested Methodologies and a Few Examples. Dumbarton Oaks Papers No: 54. Washington D.C. Text available at:http://www.doaks.org/resources/publications/dumbarton-oaks-papers/dop54/dp54ch13.pdf Retrieved 16 Oct 2017

Van Millingen, Alexander (1912): The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. Available at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29077/29077-h/29077-h.htm Retrieved 16 Oct 2017

Categories: Uncategorized | No Comments »