This is the gem of Istanbul. (41.031327, 28.939184) If you see only one thing from ancient Constantinople, let it be this. My two-year-old daughter is entranced by the glory of the mosaics and the clarity of the imagery. I’m just gobsmacked that such fabulousness has survived through such adversity.

Unfortunately, the nave is closed for restoration in December 2015. There are only a couple of mosaics in there but they are particularly nice. You also miss out on seeing the lovely marble of the main part of the church. The great mosaics and frescoes in the narthex are still accessible.

Van Millingen’s exhaustive investigations led him to the conclusion that a church existed on this site late in the 3rd Century. This was apparently a sort of martyrium, being the burial place of the remains of Babylos of Antioch and his followers. The story goes that Babylos refused the Roman emperor Numerian (Diocletian’s predecessor) entry to his church and was detained, dying in prison as a result of torture. According to Syndicus (1962), this was the first example of translation of the relics of a saint from the site of martyrdom to a church elsewhere. However, Babylas died in Nicomedia (the present-day Izmit) in 298 and his remains were in Daphne, near Antioch (Antakya) by 351. He can’t have stayed in Chora for very long. However, he had returned in the 9th century. His relics appear to have been well-travelled.

The church is traditionally known as a part of the Monastery of St Saviour in the Chora. The meaning of Chora (Χώρα) has been the subject of much debate as its general meaning of ‘region’ spans a spectrum from country (as in a rural area outside a city’s walls) through to Basileia (βασιλεία) the kingdom of an Emperor or the higher sphere of the Kingdom of God. Some scholars, such as van Millingen (1912), believe that the monastery was named after the higher kingdom of God. Others, such as Mamboury (1924), incline toward the idea that Chora referred to being in the rural hinterland in the way that the Church of St Martin in the Fields in London once meant but clearly isn’t applicable now.

The church is obviously within the current walls, built in the time of Theodosius in the early 5th century. However, any building established on the current site of the Chora before then would have been outside the walls of Constantine. Mamboury cites evidence that Justinian (527-565) restored a church here but the simple basilica that appears to have resulted from this was insufficiently notable to be recorded in Procopius’s Buildings, that paean to the bricks-and-mortar glories of Justinian.

The church was the burial place in 740 of the learned Patriarch Germanus. He had been an opponent of Emperor Leo III’s iconoclasm and as such, the Chora became a rallying place for those who still incorporated ikons in their worship. The monastery and the monks thus became a target for the hatred of Leo’s son, Constantine Copronymus (Constantine, whose name is shit), possibly not a name the use of which the emperor encouraged. Any interior decoration that had been in the church at this time would have disappeared then. The church failed to align itself with the winning sides of several subsequent disputes with the result that the place was in a sad state as the 11th century dawned.

So the current church seems to have come about in the late 11th Century, restored (according to Mamboury) or founded (according to Freely, 1983) by Mary Doucas, a very well-connected lady who connected the courts of the Bulgars and the Byzantines by marriage. Her church had some interesting structural instabilities which resulted in the need for the apses to be rebuilt in the 12th century.

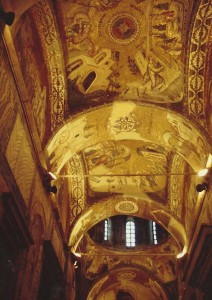

Enter Theodore Metochius, a renaissance man in the court of Emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus. In 1321, he completed his dazzling reconstruction of the Church of St Saviour in the Chora, much of which is still present. Metochius had accumulated immense riches in his passage up the ziggurat of Byzantine power. The only way for a devout citizen of Constantinople to display such enormous wealth was to build the greatest gallery of late Byzantine art that existed in the city.

Due to the accumulation of stonework of various ages in the structure of the church there is dispute over whether Metochius built or reconstructed the two narthexes and the parekklesion, but it is in these areas outside the significantly older nave that he concentrated the glory of his pictorial Bible.

The exonarthex is the gallery for a sequence of the life of Mary and the early life of Christ. There are a good few pieces of the mosaic decoration missing, but the 19 scenes of the lives of Mary and Jesus are beautiful. The exterior narthex includes the southwest room at the entrance to the parekklesion. This room holds a particularly lovely non-representational dome decoration and in the lunettes below is depicted, with notable savagery, the massacre of Herod.

The lunette over the central doorway leading to the inner narthex has a large mosaic of the Pantocrator bearing the inscription: IC HC. I ΧΩΡΑ ΤΩN ZΩΝΤΩΝ (Jesous Christos en chora ton zondon). My translation of this, with the obvious influence of the King James, is “Jesus Christ: The kingdom in which we dwell.” The stumbling block in a successful interpretation is that tricky word Χώρα. So good luck with that.

Pantocrator with the ambiguous inscription: IC HC. I ΧΩΡΑ ΤΩN ZΩΝΤΩ. Water into wine and loaves and fishes above.

The interior narthex continues the mosaic cycle of the deeds of Christ. This is a lovely room with the glorious decorations of the domes at the south and the north. From the height of the south dome glowers a particularly fine Christ Pantocrator flanked by 39 of his ancestors, including such dignitaries as Adam, Noah, Abraham, Jacob and Joseph (of dreamcoat fame).

The north dome hosts a stylised Theotokos with a luminous Christ child. Around the dome are various kings of the House of David and other prominent inhabitants of the Old Testament who have been claimed by miscellaneous scholars to be indirect ancestors of Christ.

North dome of the inner narthex. Theotokos flanked by David, Solomon, Moses, Job and many other worthies.

The mosaics of the inner narthex depict Christ healing a bewildering array of ailments, culminating in the splendid ‘Christ healing a multitude afflicted with various diseases’ executed after the artist had run out of specific text references.

Most of the nave is coated with lovely matched marble panels but there are a couple of fine mosaics. As with most Byzantine churches, the nave is surprisingly small for such a prominent religious establishment – about the size of the average classroom. There is a partially restored Mary Hodegetria on the right as you enter. This has a finely wrought face and another reference to Χώρα as the ‘dwelling place of the uncontainable’. For me, this is evidence that the Chora in the Monastery’s title referred to the Kingdom of God rather than some idea of the place being out in the sticks.

And the parekklesion. Heaven and hell, life, death, judgement, resurrection and eternal consequences. All done in fresco worthy of Leonardo. The dome has another Theotokos, a subject that seems far more suited to the medium of fresco than mosaic. The facial detail is particularly expressive. Beneath Mary in heaven is the court of angels and below this is Jacob’s ladder, the Miroesque pathway of hope to the celestial hemisphere.

For details of each picture, go to John Freely’s incomparable 1983 Blue Guide. It’s out of print so if you can’t find it, here’s a link to van Millingen’s description from 1912.

The Church of the Chora had a pretty bloody time of it in 1453. It was close to the walls so the sacred ikon of Mary Hodegetria was brought from its monastery close to the sea walls and placed in the zone of greatest peril, in the Chora. The church was one of the first places to be overrun by the forces of Fatih Sultan Mehmet. The ikon disappeared forever and the church suffered greatly. It languished in dereliction for decades until the Vizier Atık Ali Paşa restored it as a mosque. It may be to this great eunuch that we are indebted for the current presence of the church’s decoration. Rather than scouring the glittering decoration from the vaults and domes, he had them covered in a sober coat of whitewash, thus preserving them until 1860, when Pelopidas Kouppas, a Greek architect, rediscovered them in the partially collapsed building. The results of the subsequent partial restoration are visible in van Millingen’s illustrations from 1912.

What we see now is the product of the restoration by the Byzantine Institute of America that began in 1947. The hero of this project is Carroll Fenton Wales who entered the programme in 1952 and brought scholarship, artistic sensitivity and an obsession with the craft of the Byzantine mosaicist. His work is the reason that we are able to see such a gorgeous monument to Byzantine grandiosity and Christian artistry.

The Monastery of the Chora appears to have had a particular significance to the forces of Mehmet II as they conquered the city. This scene from the 1453 Panorama museum constructed in 2009 shows the Chora in unrealistic proximity to the walls. This is understandable that the artist would make the church so clear because the ikon of Mary Hodegetria which was kept there during the siege was seen as the symbol of Constantinople’s immortality. Fatih’s troops headed straight there and the symbol, and Constantinople’s Christian primacy, were destroyed..

Categories: Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

December 22nd, 2014 at 9:29 pm

[…] name ‘Hodegetria’ means She who shows the was. The ikon appears to have been taken to The Church of St Saviour in Chora during the 1453 siege and subsequent conquest by the Ottoman forces. This is the last anyone saw of […]