Mosaic of the Virgin and Child in the apse, 867 AD. This appears to be the first mosaic completed after the iconoclastic period.

Many people have written about this church (41.007982, 28.978812) much better than I can. Try here (from p253), Richard Davey’s account of Sancta Sophia towards the end of the 19th century. Or for a contemporary account of the church in Justinian’s time, go here. It was written by Procopius, probably in fear of his life if he wasn’t grovellingly effusive.

The outside of the building looks squat and blocky because of the massive buttresses that were added during its long history. These do a marvellous job of holding the thing up so it seems curmudgeonly to complain. But try standing on the Galata end of the Metro bridge across the Golden Horn. Gaze at Aya Sofya. Imagine it without the minarets and buttresses. From the constraints of utilitarian practicality emerges the elegant, finely proportioned marvel that once crowned Byzantium. Two of its mosaics are among the finest that art has to offer the world.

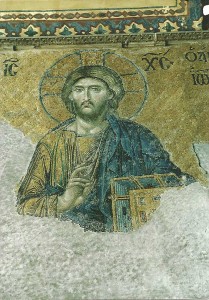

The Deësis (Entreaty) mosaic, from immediately after the end of the Latin occupation. Christ Pantocrator considers the fate of humanity on Judgement Day. The Virgin Mary and John the Baptist are giving helpful advice out of shot on the left and right respectively.

The queues to get in are awful. Try about 4pm on a cold day. No more people are allowed in after 4:30 and it can get almost lonely in there. The resident cats are friendly. The mosaic of the Virgin and Christ child above the sanctuary is astonishing.

Mamboury traces the history of Ayasofya from a basilica built by Constantine I in 325. Freely puts the date of completion of the first church as 360 during the reign of Constantine’s son, Constantius. Whatever its construction date, it was smacked down by the violence of public opinion in 404. John Chrysostom, the Patriarch at the time, won the favour of the populace and the ire of the rich with his suicidally tactless rants against the Byzantine court. The Empress Eudoxia, after a highly entertaining public debate regarding Eudoxia’s moral fibre and the wisdom of having a giant silver statue of her erected provocatively close to Sancta Sophia, banished John Chrysostom (Now St John, so the verdict of history is clear) to Armenia. The church perished in riot and fire.

Theodosius II had put up another great basilica by 415, some of the foundations of which are still visible to the west of the current church. This was destroyed on the first day of the Nika Revolt in 532. The famously self-glorifying Justinian I and his controversial wife, Theodora, had been polarising public opinion for the five years of his reign with his ruinously expensive empire restoration plan. Things reached crisis point at the chariot races. At the time, the two main factions, the Blues and the Greens, had a rivalry something like that of Red Star Belgrade and Partizan Belgrade in the final years of the Yugoslav Republic. The ramifications of this friction went far beyond the races and underlay the political life of Constantinople.

In January 532, Justinian was planning the execution of several Blues and Greens over murders committed during a previous Hippodrome riot. Two (one Blue and one Green) escaped and holed up in a church. The two factions demanded that the renegades be pardoned. Justinian responded to the unrest by providing Bread and Circuses, announcing a day of chariot races on the 13th. The race meeting began with partisan chants relating to the factions but as the day went on, the shouting became coordinated into cries of Nika! or ‘Conquer!’. The crowds began an assault on the Great Palace, lit fires and burned the Theodosian church down.

Justinian emerged from conflict with fifty thousand slaughtered citizens and no political rivals. He was now free to tax the remaining populace as much as he wanted to finance his grandiose engineering projects. The grandest of all was the new Sancta Sophia. Visitors to Selçuk (near Ephesus) have pondered over how a wonder of the world, the immense Temple of Artemis, could have disappeared so completely. A bit of foundation and a forlorn column put together from odd bits of stonework are all that remain. The answer lies in Justinian’s quest for building materials for his new flagship building. Mamboury reports that the starting point in construction was the arrival of eight big porphyry columns from the Ephesus temple. These had originally been taken from a temple in Heliopolis. The whole empire was pillaged for the finest materials, whether or not they were already parts of buildings. This is similar to Süleyman’s policy regarding the construction of the mosque that bears his name.

Justinian’s masterpiece was begun immediately after the riots and dedicated in 537. The immense foundations were sunk deep into the rock and a series of cisterns was incorporated into the basic design. The dome is obviously the whole point of the building. It was built of very light brick in contrast to the poured concrete construction used for its predecessor in circular grandeur, the Pantheon in Rome.

It was a glorious construction, a finger thrust in the face of practicality, economics and the world in general. The magnificent dome lasted twenty years, when one of Constantinople’s earthquakes shook it to the ground. Isidore the Young, a nephew of Isidore of Milet, the original architect, rebuilt the dome with a higher profile and somewhat less trust in divine protection.

Subsequent earthquakes necessitated further modifications as the centuries passed. Buttresses were necessary to strengthen the church but over time they began to obscure the pure lines of the original design. The first of these were on the north and south of the church and were probably added by Isidore the Younger. Massive flying buttresses were added late in the 9th century.

This is said to be the burial site of the Doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo, who led the Venetians in the sack of Venice when he was blind and 90 years old.

The worst disaster to befall Sancta Sophia was the Latin invasion of 1204. Three days of awful desecration were followed by neglect as the isolated Latin Empire ran out of money and support. Anything moveable had been looted or melted down. The fabulous collection of relics was shipped off to the west and artifacts in gold, silver or bronze were melted down into unidentifiable additions to the fortunes of the Crusaders. By the time Michael VIII Palaiologus retook Constantinople in 1261, Sancta Sophia was in a poor state. The new regime was not exactly rich but the symbolic importance of the church meant that it was a priority for restoration. Andronicus II had four great buttresses built in his restoration in the early 14th century. As the fortunes of Constantinople slowly wound down, the great church again fell into disrepair.

Sancta Sophia remained the spiritual centre of the empire so that when Mehmet II’s army besieged the city, many people gathered inside. Hence, when the Ottoman army smashed its way into Constantinople in 1453, the slaughter in the church was terrible. After three days of pillage, a time which seemed to be something of a rule in those days, Sultan Mehmet entered the hastily tidied church and ordered its conversion into a mosque.

Two bursts of iconoclasm in the 7th and 8th centuries would have destroyed most representational art in the church so the mosaics now present are from after 843. Many date from the restoration carried out under Basil II after the earthquake of 989. The acquisitive Latins packed up several of the more spectacular gold mosaics and some may now be seen adorning churches in Italy, particularly that warehouse of plunder, Basilica San Marco in Venice.

The invading Muslims were kinder to the sacred artworks than the Christian iconoclasts and crusaders. They painted or plastered over them, a move that tended to preserve rather than destroy. The mosaics stayed beneath the plaster until the arrival of the Fossati brothers in the 1840s. These Swiss architects built nearly every important building constructed in the Tanzimat era, the period of sweeping reforms of the Ottoman Empire. Sultan Abdulmecit hired them to renovate Ayasofya, which they did in two years with the aid of 800 workers. While their brief did not include the restoration of the mosaics, they did document them carefully. The surviving records show several mosaics that no longer exist.

May 2016. The scaffolding no longer covers the mosaics of the bishops in the blind arches on the south side of the nave.

In 1895, Clara Erskine Clement reported that she was offered as a souvenir a handful of mosaic pieces, as did Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. This sort of treatment was routine and undoubtedly resulted in the disappearance of mosaics already in a state of decay. The Byzantine Institute of America began restoring the mosaics in 1931. This rather touching 1936 letter from Royall Tyler, one of the founders of the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine art collection, to Mildred Bliss Barnes, gives a good impression of the scope of the work that was being done then.

The most recent intervention has been a full restoration of the dome, supported by the World Monuments Fund. This immense task lasted from 1997 to 2006. Scaffolding is still a common sight inside Ayasofya as parts of it are continually needing attention. The font was recently uncovered in the baptistry. In 2009, a covering was removed from the face of a mosaic of a seraph on one of the pendentives of the dome.

Justinian I (left) presents the church and Constantine I offers the city of Constantinople to the Theotokos. From the time of Basil II.

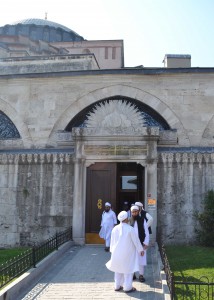

In 1935, Atatürk took the rather provocative step of turning Ayasofya from a mosque into a museum. However, the south-eastern part of the Ayasofya complex, near the Topkapı Palace gate, is (as of 2014) open as the Ayasofya Camii. It appears to be a kind of study area for visiting Islamic scholars.

Categories: Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

July 1st, 2014 at 5:33 am

[…] Aya Sofya […]