I left Taksim Meydanı after the fireworks. Thousands of people were milling around, singing, shouting, enjoying the feeling of being at the centre of everything. If you turned on a television now, it would show this place and its churning, writhing party.

My friends were going on to a bar but Not With My Sister was due to play at 2am. We were booked with three other bands for the Flatline New Year’s Eve Party. Flatline was Istanbul’s capital of grunge: on the bill tonight were Lemmings, Cockroach, Not With My Sister and Indians. We were a sort of collective of bands, all interconnected, sharing musicians and ready to stand in for each other in cases of illness or missing bass player.

I pushed through to the edge of the crowd and headed down towards İnönü Stadium where I might get a taxi. I saw people I knew. Their plans all seemed to involve being at Flatline at some time of the evening. It took time to navigate the sociable crush. I would probably be late but it had never mattered before. I found a taxi at the bottom of the hill and we nosed into the hooting but, for once, happy gridlock.

After twenty minutes, we hadn’t moved so I paid off the driver and walked into Ortaköy. It was unusually mild for New Year and the crowd outside Flatline was smoking, drinking and making itself heard, something that couldn’t be done inside.

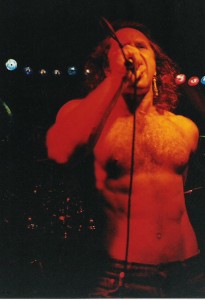

Not With My Sister’s first gig was in 1994, at a small bar in Ortaköy. This was Abstrakt, newly opened and fitted out with a décor of serrated, arc-welded slab steel. My natural habitat. I wasn’t really prepared. I knew the songs and had all the vocal tricks down well. It was a few months since I had performed and Ortaköy was a new and cutting-edge entity for me. Still. I was fronting what I was certain would be a force in the music scene and the fretted decoration was eminently climbable.

We crashed into the first song. The sound was a bit off so I covered with more screaming than usual. That went down well. By the time our sound guy had the levels right, people were coming in off the trendy craft-market area to find out what the noise was. I had an audience. My Turkish was awful so I didn’t have much between-song patter to hold the audience while my bandmates did the endless tuning and effects adjusting that they said was necessary.

So I started climbing and singing. Thank the lord for cordless microphones. After a few seconds, I was on top of a saw-bladed booth partition staring down at some startled couples and howling ‘New York, New York’ at them. That seemed to go down well. Everything went down well. If I partitioned my sense of reality off and just did what my mischievous little inner child suggested, I could get away with anything.

This set the tone for my performance for the next decade.

Ortaköy itself was heaving. There were no enforceable licensing regulations on New Year’s Eve. The traffic was less good-natured here, with most people trying to get home after their family gatherings. Children were sleeping in cars and the periods of immobility were so long that drivers were dozing off too. Occasionally there would be a fresh burst of hooting as a car moved a length forward. The horns would wake the rest of the drivers up and the whole Tetris grid would adjust again.

I shoved through the people into Flatline. The temperature and humidity rose sharply as I moved inside. So did the volume. It took me a while to get used to the noise and darkness. I began to recognise people and sounds. The band was Lemmings. They were supposed to finish at midnight. It was after two. I passed by the bar and got a drink. There was an air of anarchy that I wasn’t used to in Flatline. It felt as if something was going to happen. I wandered up to the stage and joined a clump of musicians. They told me that there had been some kind of electrical problem. Lemmings had started late and they were likely to be playing for another hour.

The place was jammed. There was a regular sound of glasses breaking and being trodden into the floor. I wasn’t used to this. It wasn’t that kind of place. Still, it was New Year’s Eve. Lemmings were doing nicely and there was another and on before us. Some of us went out for some food. The narrow alleys of Ortaköy were packed with people eating and drinking and talking. We found a dürüm place, got our food and went down to the water to relax. Other band members were there. Bottles of Scotch circulated. I had some, then went back onto beer.

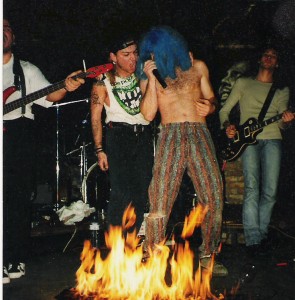

We were in the middle of some grunge song when I noticed a flash of blue out of the corner of my eye. The bar was packed. It was raining outside and people were crowded in. It had been raining for over a week. People were sick of it and were no longer content to stay inside. So here they were. Flatline looked somehow simultaneously cool and friendly when you looked inside from the street. It had good music (us) and it had a comfortable but punk-jagged décor that people liked. It was still early, about 11 and we had begun our first set with the sort of energy that we needed to show people that it was going to be worth staying until 2 or 3.

I felt nicely at home. The mix sounded good and there was no trace of the sore throat I had struggled with for the past few weeks. The crowd was still building. People sitting at the bar were enveloped by the standing throng. People were starting to dance. I kept a proprietorial eye on proceedings as we built the atmosphere. Then I saw that flash from above the bar. I kept singing but looked more closely. It came and went, an electrical discharge that shouldn’t have been there.

Everything went on as normal. Kerem, the bar manager was in his usual position in a corner of the room. I caught his eye and pointed to the sizzling blue. He smiled and went back to his conversation. Maybe he knew about it. We finished the song. I asked the bass player whether he had seen it. “Come on,” he said. People were waiting. We crunched into a Rage Against the Machine cover. The atmosphere cranked up a notch. There was a mosh pit now. The stage diving started.

I looked at the place where the blue had been. Nothing. Then it started. A flicker of electric blue, then it spread in a line along the ceiling above the bar. A chunk of plaster detached and fell. People stopped and looked up. Sparks flashed along from one side of the bar to the other. In slow motion, a section of ceiling unpeeled itself and plummeted onto the crowd by the bar. There was dust everywhere. That sapphire will-o-the-wisp sputtered away above the mass of people writhing on the floor.

I looked across at Kerem again. He raised his eyebrows and shrugged. We kept playing. Our power was still on. The roiling maelstrom in front of the stage hadn’t noticed anything. I finished a chorus, jumped onto the moshers and made my way to Kerem “Should we stop?” He pointed at the rescue effort that was under way. Someone had turned off the power to the lights above the bar. The dust was settling. The injured were outside. The biggest slabs of plaster had been dragged onto the pavement. “Keep playing.”

I muscled my way back to the stage just in time for another burst of revolutionary poetry. The song finished. People were starting to come back in. They were given drinks. Nobody was badly hurt. A couple of people were bleeding a bit from cuts to the head. They were seated at bar stools and allowed to recuperate with medicinal alcohol.

The incident was never mentioned again. It wasn’t that anyone was trying to hush it up; nobody seemed to think that it was worth talking about.

When we got back, Lemmings had finished and Cockroach were setting up. It was quieter without the bands but still loud. The air was almost opaque with cigarette smoke and the humidity was at sweaty sauna levels. Cockroach started their first song. Deniz, the singer, went for an introspective, moody delivery that matched the thick air. I went into the back room. Eddie the cat was asleep on the main power amp. I lay down on the cushions at the side and imitated him.

“Come on.” It was Seha, our bass player. “Time to play.”

“OK.” I opened my eyes. The back room was full of smoking people. Some of them were arranged in interlocking couples. In one corner, someone was having their ears pierced with a lighter and a needle. I got up and took my gear to the stage. Cockroach were looking happy. The bar wasn’t quite so crowded now. Most people were having a breathing break outside before resuming their mission of seeing the New Year in with the maximum of ear and lung damage. I set up my receiver and plugged in. A quick sound check and we were ready.

Deniz slung an arm around my neck and said, “Look out for the glass.” I had a habit of launching myself off the stage onto whatever was there. Deniz pointed at the bit of clear floor in front of the stage. It was ankle deep in glass. I went to the bar for a coke. There was nobody there. I ducked under the hatch and got a can from the fridge. Someone asked for a couple of Efes. I didn’t know how much they cost. It didn’t matter. They gave me some money and I put it into the unlocked cash register. I served drinks for a while. I wondered where the bar staff had gone.

Being a regular on the Istanbul rock circuit meant guesting with other bands. If a musician was recognised by the performers on a given night, it was considered polite to invite him or her onto the stage for a song or two. I embraced this practice wholeheartedly when we were playing because it would give me a rest and time for a relaxed drink.

This also meant that if a singer from another band was out of action for any reason, I would get drafted in to replace them for a while. I fronted a band called Lemmings for a while when their singer was studying elsewhere. I liked them and I was familiar with their repertoire so this was quite a pleasant change.

One Saturday, we had done a good night in Flatline in Ortaköy and were about to pack up. A large American approached the stage and began shouting. It took a while to realise that he was being tremendously complimentary. “You’re a great band,” he said. “I’d have to pay hundreds of dollars to hear a band like you in the States. So here’s hundreds of dollars.” He then proceeded to give us a handful of hundred dollar notes. He then bought us a round of drinks and left.

After a while I wandered back to the stage. All the guys from Indians, the last band on the bill were there. They were supposed to play at 4. It was now after 5. People were starting to come back in from outside. I saw Kerem, the bar manager. He was arguing with the owner, an older man who I hardly ever saw. Apparently, it had been so rough during the last set that the bar staff had gone home. The owner said, “You’re the manager. You deal with it.” Kerem said, “This is how I’m dealing with it,” and left. The owner looked at me, shrugged and disappeared as well.

I responded in a practical manner, filling pint mugs with beer for all of my band mates. I shut the cash register and placed the feeble barrier of the hatch down. Back to the stage. Indians were looking doubtful. They had played somewhere else before coming here. Their equipment was in a car double-parked outside. This was not a particular problem as the traffic had subsided. Still, they were tired. They stood around morosely in a sea of glass, watching the punters come back in.

We got on stage and plugged in. Within the first few bars of the first song, the mosh pit was a seething mass of projectile people. It got safer as more joined them. Now there were too many people for them to build up dangerous momentum. It was harder to fall onto the broken glass. Physics to the rescue. They were also more tired than they had been. They took the absence of bar staff in their stride. Most of them didn’t drink any more. Sometimes there were people behind the bar. There was nothing I could do about it. It would have taken quarter of an hour to get across the floor to the bar.

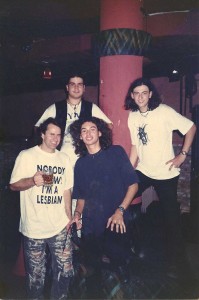

After one performance at Flatline, a girl wanted to talk to me. This was normal. If I sang lyrics about disorientation and alienation, I must be able to help people who felt these things. This girl approached me as I was packing up. She sat me down on the front of the stage, faced me and took a breath.

She pointed at the T-shirt I was wearing. It said Nobody Knows I’m a Lesbian. I had bought it from a stall in Camden and worn it as a bit of a joke. It wasn’t a joke to her. “Can I have your T-shirt?” she said.

“Why?” People didn’t usually ask for my clothes. She must have a good reason.

“I’m a lesbian,” she said.

“I see.”

“I’ve never told anyone.” She looked at me earnestly. “This is it. I’m coming out.” She gave me a shivery little smile. “I knew you’d understand.”

I took my T-shirt off. I got hers in return, a nice Phantom one but about seven sizes too small.

I saw the girl in the Lesbian T-shirt quite a lot after that. She introduced me to her girlfriends and treated me like a favourite uncle.

It was a great gig. Any inhibitions had been lost hours ago and anyone who was left was there because they were having a good time. Someone touched my arm. It was the singer of Indians. They were leaving. I waved and watched them plough through the densely packed humanity. It was an odd situation. More like a private party than a job – just us and the crowd. We launched into one of our standards – an upbeat song about suicide. I finished the second chorus, raised my arms and screamed. I felt pressure under my arms. The crowd knew the song as well as I did. I relaxed and felt myself rise into the air. A bed of hands passed me back through the club. They stopped. I was at the other side. I stepped down on to the bar and sang another verse/chorus. Then I ducked behind the bar and got myself a drink. The passage back to the stage was so smooth that I didn’t spill a drop.

The atmosphere didn’t flag. I didn’t know what the time was but we had played over thirty songs. I still had a voice. People were still moving and shouting. All of us still had adrenaline. We were well into our stock of old cover versions by now. It didn’t matter. The crowd was so full of alcohol and whatever that they would enjoy everything. I was glad I had that sleep in the middle of the night.

Eventually, a few people started to go. There came a time that seemed like the right one to stop. We announced the last song. People were ready. We finished. People slapped us on the back, invited us to parties, then went home. As the population density decreased, I could see that some of the punters had bleeding legs. When the floor cleared, we could see that there was jagged glass up to mid-calf.

We packed up and gathered at the entrance. It was light outside. The street was a deserted New Year’s Day grey. We wondered what to do. None of us had a key to the club. Normally, Kerem would be there to do what had to be done. I checked the cash register, fully expecting it to have been looted. It was overflowing with notes. There was a pool of money on the floor in front of it. We paid ourselves from the register, shut the outside door and went home.

We played at Flatline again on the following Friday. Everyone was there: Kerem, the owner and the usual bar staff. Whatever had happened on New Year’s Eve was forgotten.

More Not With My Sister stories here and here.

Posted April 9, 2014 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Not a bad mid-life crisis. A little early. I was 29.

I was teaching in a school in Kangaroo Island, South Australia, when the guitarist of a band I had once been in called me and said, ‘What do you think of moving to Sydney and playing bass and singing in a new band?’ I went to see my Headmaster who laughed and said, ‘As if.’ So I went.

Some of our guitars

We lived in a townhouse that we couldn’t afford in the beautiful suburb of Manly. We had a surf beach 50m in one direction and a harbour beach 50m in the other direction, where I attempted to windsurf . The house was full of musical instruments and our neighbours suffered.

I busked in Manly and on Circular Quay for a while, then found jobs in a pizza shop and a gym. The band never got off the ground but I found another band fairly quickly.

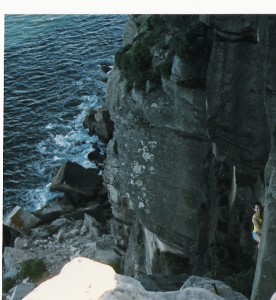

Just up the road was North Head, a surprisingly pristine wilderness area with cliffs and echidnas and Eastern Water Dragons. I did a bit of rock-climbing there…

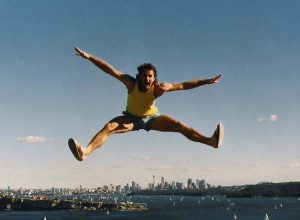

…and the drummer took this picture of me leaping from a fence over Sydney harbour.

Flying over Sydney

No Photoshop back then.

After a short time, I was as busy with three jobs (pizza, gym and band) as I had been as a teacher, so I got another teaching job, made a bit of money and went to Turkey.

The Philharmonic Oysters

Next Entries »