The area north of Tophane houses a conglomeration of ruins of mixed Byzantine and Ottoman origins. One of the more interesting buildings here is a hamam (bathhouse) which appears to have been founded in Byzantine times and renovated and added to ever afterward. Between this and the coast road is the remains of a set of Ottoman artillery barracks (41.028059, 28.983344). A recent project to rebuild the barracks unearthed some rich Byzantine findings including a necropolis that appears to be linked to a monastery. This may be from the 4th-5th centuries. There is something of a controversy between those who want to examine the monastery remains and those who want to stop the archaeological work to rebuild the military edifice. We await further news.

There appears to be a plan to transform the place into an Arkeo-park under the auspices of Mimar Sinan University, similar to Koc University’s effort at Kucukyali.

Here’s the situation in July 2019.

There does not appear to have been any progress for at least a year.

Ince, E. (2016) O Lahitten Her Dag Basinda Var. Aktuel Arkeoloji (originally from Radikal) Available online at: http://www.aktuelarkeoloji.com.tr/o-lahitten-her-dag-basinda-var retrieved 14th Sept 2017

Posted September 11, 2017 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Posted September 8, 2017 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

Sandwiched between the area of the old Grand Palace and the newer Bucoleon is this undistinguished mosque (41.003265, 28.976672). Apparently, the mosque was a product of the great Sinan, constructed in 1533, but fires necessitated complete rebuildings in 1766 and 1825. The interesting thing about it, from my point of view, is the substructure. As with the Monastery of St Mary Peribleptos in Samatya, the modern structure rests on Byzantine vaults.

Kostenec acknowledges that the evidence is ambiguous, but the presence of a Byzantine building of this size aligned on an (approximately) east-west axis argues for the foundations originating as the support for a church. The building was immediately inside the wall of Nicephorus II Phocas, which places it inside the grounds of the Grand Palace as defined by these 10th century fortifications.

The south (or south-eastern) face of the substructure displays four arches, not entirely Byzantine in appearance. Presumably, some reconstruction was undertaken after one of the fires. This area is a peaceful backwater in this crowded region below Sultanahmet Camii and is comfortably furnished for local residents to enjoy family life.

The eastern face is a plain stone wall with two arched windows. The understory has remained unplastered, which allows the precise stonework to be examined.

The lower metre of so of the building immediately to the west of the mosque resembles the facing of the 5th century rebuilding of some of the aqueduct bridges in the Roman/Byzantine aqueduct system that passes beyond Vize. Especially noticeable is the protruding string-course above the arch on the south face.

The vault is accessible from the iron staircase to the ablution facility on the north-western side of the building. The western end is used for storage of building materials. The stonework has been plastered over and this makes it difficult to assess the age of this part of the building.

The vault itself is an undistinguished section of apparently Byzantine stonework. The eastern section is larger and lacks the curvature that might indicate the presence of apses that would identify the structure more strongly as a church.

A nice Byzantine touch is represented by two artifacts at the south-east corner of the mosque. A sarcophagus placed on its side and mortared into the pavement serves as a park bench. A Corinthian capital lies on its side a little to the east of this.

Fifty metres to the west of the mosque (41.003436, 28.977845), a house was demolished in about 2000, revealing some solid 11th or 12th century masonry tucked against the massive wall of the Grand Palace terrace.

According to Kostenec, this is close to the site of the 9th century Nea Ekklesia. However, this stonework dates from a couple of centuries later. It appears to be the remains of a church but it is difficult to link these ruins with any church for which records exist.

The plant growth is thick and covers most detail. However, a distinctive floor plan of a very solid building may be discerned.

There is some doubt as to whether this is a church or not. The apse faces southwards, meaning that it would be on the north wall of the chamber of which it was part, rather than the expected eastern side.

A little to the east (41.003660, 28.978167) is an interesting building that appears to be an Ottoman addition to Byzantine foundations.

This is a strange agglomeration of bits, including some 20th century plumbing. However, the lower level appears to be more consistently Byzantine. The northernmost section of the building has the most clearly defined foundations.

In the archway at the bottom can be seen a curved section of stonework supporting some later brickwork.

This resembles a small apse of a traditional 3-apse church of the 11th-12th centuries. It is on the usual eastern end of the building. The remainder of the church (if it is a church) has been obscured or destroyed by whatever has happened in the area over the last 800 years.

Almost everything underground in the south of the Grand Palace area is Byzantine. Mamboury did a sterling job in the first half of the 20th century recording and interpreting the shattered remains in what was largely a deserted area. It is a good thing that he did because almost the whole area has been covered with piecemeal development catering to our rampant and lucrative tourist industry.

One odd building across the road from the above site (41.003321, 28.977924) deserves a look. It is a narrow, precarious pile of brick with the remains of an amazing domed ceiling. Nothing to do with Byzantine churches, but worth seeing.

Kosterec, J. (2007) Walking Thru Byzantium: Great Palace Region. Byzantium 1200 Project. Grafbas A.S.

- Mamboury, E. (1953) The tourists’ Istanbul. English ed. translated by Malcolm Burr. Istanbul, Cituri Biraderler Basimevi

Posted August 30, 2017 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

In Roman times, Constantinople needed water. It was a rapidly growing city and its dry summers endangered the water-centred Roman way of life. Hadrian built a system of aqueducts early in the 2nd century that took water from Belgrade Forest. Constantine’s massive developments in the 4th century required huge quantities of water at a higher level than Hadrian’s supply. Several emperors including Valens had a new supply line built to take water from the mountain springs of mid-Thrace. This was complete by around 373AD and brought water over 100km from the hinterland.

There was still not enough water and the mountains were full of springs from which pure water gushed out and flowed to the sea. By the early 400s, the aqueduct had been extended more than 275km, beyond Vize. This is a massive engineering feat in which the tolerances were so fine that in each kilometre of distance, the level of the water fell only 0.7m.

1600 years later, the aqueduct is still there. Most of the more spectacular bridges are in a mountainous area frequented only by hunters, charcoal burners and herders. The forest is a particularly dense and spiky combination of vegetation which discourages exploration. This means that we have a relatively untouched linear archaeological site of unsurpassed quality and length. There are at least 50 bridges (probably over 100 – I keep finding ones that aren’t in the literature) and much of the tunnel arrangement that carried the water remains intact.

I have a good deal of available time in Istanbul and I use much of it in searching out the bits that people haven’t seen for a few hundred years. They are hard to find. One of the more elusive sections is on Karamanoğlu Tepe, a spur to the north-west of the village of Aydınlar. I had seen pictures of a nice-looking 5-arch structure and there were rumours of a tunnel that ran for 500m east of this bridge.

It took me two full days to find any sign of the tunnel. These were in pre-GPS days and I spent most of my time being more-or-less lost. Eventually, I found a hole that looked as if it might be part of the collapsed roof of the tunnel. The hole looked quite shallow. I was fairly tired by then and this may be why I didn’t check the floor level before I took my pack off and jumped in. What looked like solid ground was a thick, soft layer of dead leaves. I sank beneath the surface.

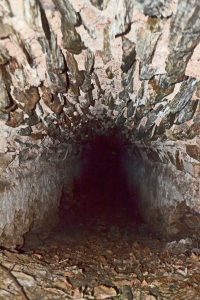

When I managed to stand up, the hole was an unreachable distance above me. The channel itself was over 2m high and this section was fairly deep underground. On the bright side, this was definitely the aqueduct so I had achieved my quest. However, my torch and ropes were in my pack, safely above ground. I tried grabbing for handholds on the open roof but could not reach the top.

The only thing to do was to go along the tunnel. There was no daylight visible in either direction but I chose one and groped along the well-defined wall. There was absolute silence. Nobody had been this way for years. Calling for help would be useless. The occasional bat thrummed past my ears. After a while, the level of the tunnel started to rise. My head hit rough stonework. My eyes must have become accustomed to the dark because I could see a light patch above me, where it had previously looked dark. I reached up and struck spiky branches. There was a hole in the roof and I was close enough to reach through it.

15 minutes later, I had bleeding hands and a hole through the roof and the thorn bushes big enough to climb out of. I hauled myself out and thrashed through the bushes to some clear ground. I wondered how I was going to find my pack. It felt as if I had gone hundreds of metres underground. But there it was, a red bag less than 20m away. I went back and looked at the hole. I should have tied a rope to those trees and dangled it into the hole. That would have saved me the needless drama.

Posted July 17, 2017 Posted by Adam in Uncategorized

My daughter and I like building things on beaches. Turkish beaches tend to be rich in building materials: rocks, driftwood and an astonishing variety of potentially useful rubbish.

A year before, we had made a single Roman arch. This time we wanted to apply that idea to a bigger thing.

On this beach , my daughter stopped to play in the shallow water where a stream flowed into the Black Sea. She began to move rocks into place.

The concept had something to do with the aqueducts that, in Roman and Byzantine times, took water the 250+ km from beyond Vize to Istanbul. This one is Kursunlugerme.

The eventual product was a seven-arch balancing act.

« Previous Entries Next Entries »